Test Pilot 1,2

My first recollection of wanting to be a test pilot was when I was 11 years old. My folks had rented out our spare bedroom to a pilot. He wasn’t just an ordinary pilot but a freelance test pilot, one who hired himself out to perform highly dangerous flight tests on new prototype airplanes. This was in 1936, which was in the days before the technology era of computers, telemetry, and so forth. The most dangerous test he did was the “power dive.” If you ever saw the old movie Test Pilot, with Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy, you know what I mean.

This test involved climbing the aircraft about as high as it would go and then pushing the nose straight down with the engine power on. It wouldn’t take too long to reach the airplane’s terminal velocity, and then came the problem of slowing down and recovery. The power is reduced, and the dive is shallowed out by pulling back on the stick. This takes time and altitude. If the flight controls are still functioning normally, the aircraft responds and turns the corner before hitting the ground.

The test pilot in this high-speed dive recovery experiences the phenomenon of G forces (gravity forces). The more he pulls the stick back, the greater the load factor (G force). The danger is that at about a sustained 4-5 G acceleration, a pilot will black out and lose consciousness as the blood leaves the brain and goes downward into the lower extremities.

The test pilot in this high-speed dive recovery experiences the phenomenon of G forces (gravity forces). The more he pulls the stick back, the greater the load factor (G force). The danger is that at about a sustained 4-5 G acceleration, a pilot will black out and lose consciousness as the blood leaves the brain and goes downward into the lower extremities.

To combat this, our “family test pilot” used to get my mom to tightly wrap his legs and abdomen with wide strips of adhesive tape. I’ll never forget it. However, now we have special G-suits, which inflate bladders automatically when necessary. Same idea! At any rate, he was quite a glamorous, macho role model for an impressionable 11-year-old.

During World War II, everyone was patriotic and doing whatever he or she could to help the war effort, from saving scrap iron and rationing gas and meat to “Rosie the Riveter” women in the aircraft industry. Naturally … the men wanted to fight. My best friend, who had terrible vision, memorized the eye chart to get in the service. In March 1943, I enlisted in the Navy Air Corps while still in high school.

In Navy flight training, only the top percent got to fly fighter aircraft in the fleet. That’s what everyone sought after, the “glamour” of being a fighter pilot – white silk scarf and all. I was one of the fortunate ones and flew the F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair. Every year in the Navy you have the opportunity to request what you want for your next assignment. I always put in for Test Pilot’s School at Patuxent River, Maryland. But, of course, the Navy put you where it wanted to. Somehow I never made it to Test Pilot’s School, but unbeknownst to me, the Lord had a hands-on training program for me at Douglas Aircraft Company.

After World War 2, I continued my pursuit of flying in the Naval Reserve “Weekend Warrior” Program and flew my first jet in 1948. With the advent of the Korean War, I again volunteered for active duty and did two tours as a carrier jet pilot flying the F9F in combat sorties over North Korea.

With the cessation of hostilities, I once again returned to civilian life, finished up my college at UCLA, and then went to work at General Motors, a good job – but my passion was to keep flying. Thus in 1956 I applied for and was hired by Douglas Aircraft Company as a fledging “test pilot,” which brings us up to our story.

Flying along, as aviation lingo would put it “fat, dumb, and happy,” at 35,000 feet, I was flying an A4D Skyhawk. This airplane was designed as a single-engine attack aircraft, capable of delivering an atomic bomb, but it flew like a fighter with its Delta wing and the fastest roll rate of an aircraft flying at that time. I was on a cross-country flight from Memphis, Tennessee, back home to Palmdale, California. It was a beautiful day with not a cloud in the sky. I had lots of gas, extra fuel with two full 300-gallon drop tanks, plus a $1.5 million dollar instrumentation store on my centerline, so I was heavier than normal.

There I was, “fat, dumb and happy,” complacent, living in the world, and oblivious to dangers surrounding me, That’s when it happened – I had just reached down and shifted my UHF radio channel to Little Rock Center, when “Bam!” my engine “flamed out,” quit. Don’t laugh, but the first thing I did was to immediately switch back to the former radio channel, unconsciously thinking that was what caused it, but the engine wouldn’t start. What did happen, along with the engine failure, was an explosive decompression. Get a mental picture of this: My oxygen mask momentarily moved away from my face and then slapped back at me. No longer could I breathe normally. I had to push against the oxygen pressure. Why? With the engine failure. I had lost cabin pressurization. My cockpit went from a comfortable 20,000 feet to 35,000 feet, just like outside. Worse than that, the cockpit was momentarily filled with fog. When it had dissipated, my entire canopy was fogged over. The only place I could see outside was a small, football-sized clear area directly in front of me on the windshield armor-protected glass.

My training kicked back in as I realized what had happened. The first order of business was to manually extend my emergency generator into the slipstream outside of the fuselage. This gave me back electrical power, and my radio was functioning once again. I reestablished communication with the Little Rock Center and declared a “Mayday,” the International Emergency Distress Call. They came right up on frequency, acknowledged my “Mayday,” and told me they had radar contact.

I decreased my airspeed to 200 knots, which was the optimum glide speed for distance versus altitude. As I started to descend with a vertical rate of descent of about 5000 feet per minute, I repeatedly tried to re-light (start) my engine, but to no avail. Where exactly was I? Little Rock Center said I was over Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and that it had a small airport. With not much time to make a decision and not enough altitude to glide to Little Rock, Arkansas, where the closest major airport was, a forced landing in the woods seemed almost inevitable. Then, rolling my airplane over, I saw this little Pine Bluff Airport – no tower operator, no emergency equipment, no traffic – only this single short 5000-foot runway to make my flameout approach and dead-stick landing. This was a far cry from the 11,000-foot runway at Palmdale where I had practiced landings with a simulated engine failure – but it looked beautiful to me! It was true that my Skyhawk had an ejection seat, which would blow you up and away from the airplane and automatically open your parachute, but at this juncture in its development only about 50 percent were successful ejections. (Later, it became almost perfect.) Those odds weren’t to my choosing, and I had confidence that somehow I could make the runway. Now I had renewed hope!

In our A4D flight manual it describes the best, and right way, to make a successful flameout approach and landing. Can you visualize a wire that circles down from overhead the runway at 9000 feet, making a 360-degree turn as it descends and then touches the runway at the touchdown landing point? Well, that’s the flight path, the pathway, so to speak, that the A4D must follow to make a successful landing without engine power. Not only does the airplane pilot have to intercept and follow this track, but also he must be in the right configuration – flaps down, landing gear down, and on the correct glide speed. Changing, or varying any of the above means failure, a crash landing before the runway or not being able to stop on the runway.

It is absolutely mandatory to intercept and follow this flight path in configuration and on speed for success. However, it is not necessary to start at the top at 9000 feet, called the high-key position, or even to start at 4500 feet, which is the low-key position, abeam from the runway, but you must intercept it at some altitude before the runway. Obviously the sooner the better, and the closer you adhere to it the better you feel.

My aim was to cross the approach end of the runway at 9000 feet in configuration. By this time, I had already lost 15,000 feet of altitude, but I still had plenty of altitude left to maneuver myself into position. Due to my “football-sized” view ahead and nothing to the side, I had to do some crazy gyrations to keep the runway in sight. I knew I was about 5000 pounds heavier than normal with my external gas tanks and centerline store, which added to my aerodynamic drag. This extra weight and drag were also my “ace I the hole.” I said to myself, “If it looks like you’re going to be short of the runway, then pickle [jettison] them off, and that should make up the difference.” The surrounding terrain was wooded, and fortunately there were no houses at all on the last part of my pattern.

I advised Little Rock Center that I was starting my approach – still no communication with Pine Bluff. The first 180-degree turn was right out of the book, and I hit “low key” abeam right at 4500 feet. Good! One more 180-degree turn to go. As I was approaching the last 90 degrees of my turn, I felt I was lower than I should be. I made a quick check to make sure all my switches were in the correct position to drop my 300-gallon gas tanks. They were, but I decided to wait a little longer – running off the runway was almost as bad as hitting short. At the 90-degree position, I made the decision to press the pickle switch on my control stick. Nothing happened – no lift which is typical when you drop a heavy weight. I frantically pickled again and again – no drop. The switches were on. Why no drop? In the Skyhawk you have two red handles located just below the instrument panel in front of your knees to mechanically release the tanks in an emergency. I yanked on them but still to no avail. The gas tanks were still attached to my airplane.

That was my last resort, and now I was at the 45-degree position and too low, dangerously low. As I saw the ground and trees so close and so little time, all of my instincts told me to pull back on the stick and slow my rate of descent, but that was the wrong thing to do. True, it would increase lift for a while, but it would also increase drag, with the end being negative. Lineup on the runway was okay, so I kept my 170-knot speed (192 miles per hour) right down to tree-level height. This gave me the added benefit of ground effect (some extra lift derived by the close proximity to the ground). So now I just held the airplane off and watched my airspeed slowly decrease. Would I be able to keep flying and make the runway before the airplane stalled and crashed? Now I was in the cleared area just short of the runway. The runway lights at the end were in sight.

Well, I made it, just a few feet from the end. Stopping proved to be no problem, and I was motionless at about 3500 feet with 1500 feet of runway to spare. I thanked God for my safety and then opened the canopy and looked around. It was eerie, like I was the only one left on earth. No people, no crash equipment, no fire engines, and no ambulance. I climbed down. The airplane looked normal, and my brakes weren’t even hot, but there was not a sign of life except a swallow singing beside the runway.

After 10 to 15 minutes, I had just about decided to leave my airplane and make the long hike to get help when I saw a red jeep enter the runway. When he pulled up and saw that I was all right and the airplane not damaged, he dug out an old chain, which we attached to the nose strut, and away we went. What a picture and no camera!

When we got to the hangar and chocked the wheels for safety, and since this man had already let Air Traffic Control know that I had landed safely, I asked for a telephone to call my boss. The first thing I told my boss was that I was on the ground in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and that I wanted a raise.

As you can surmise, Pine Bluff was a pretty small town when I “dropped in.” It made quite a bit of excitement. I even got my picture on the front page of the local newspaper standing by my A4D Skyhawk. I found out that I was only the second jet to ever land there. The other aircraft, a P-80, had trouble stopping and went off the end, and his engine was operating.

Well, Douglas Aircraft sent out a team of mechanics, and it proved to be a simple fix. Three days later, I took off, with many new friends and other spectators from town watching. They had requested an air show, so I obliged them by doing a slow roll on takeoff and a flyby. OOPS! The editor of the newspaper sent the story and picture to my boss, but I still got the raise!

1 From “Wakeup Call,” Fundamental Evangelistic Association, Box 6278, Los Osos, CA 93412, USA (undated).

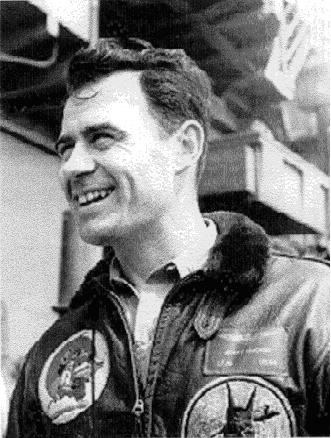

2 Jerry McCabe was recalled for the Korean War while in the Navy Reserve and attending UCLA. He served two tours in Fighter Squadron VF-781. After release from active duty he was a production and experimental test pilot with Douglas Aircraft. He was chief pilot on the DC-10 project.