My Adventures With The Bent Wing Bird

My Adventures With The Bent Wing Bird

By The Rev. Richard A. Cantrell, SSC

Recalling What it Was Like Transitioning From The SNJ Texan

To The Mighty F4U-4 Corsair

There I was at 1200 feet – and I had finally located the altimeter! The problem was we all had been told to stay below 1000 feet until we were clear of the nearby commercial field. Fresh from basic carrier qualification on SNJ Texans, I was making my first flight in a Corsair, an F4U-4. It was only the first of seven unforgettable flights in the old bent-wing bird. Two were at the beginning of advanced training, one in the middle, and the other four at the end.

I remember having two thoughts as I added power for takeoff. First, that I was riding the barrel of a 13-foot cannon; and second, as I got airborne, that now I had flown a Corsair. No matter what might happen after that no one could take that away from me. By then, I was above 1000 feet and still looking for the altimeter. There was sim-ply no way to get ready for the difference in the speed with which things happened in the Corsair compared with the SNJ. The rest of the flight was normal, and I somehow avoided a mid-air collision with any of the commercial planes from the other airport.

When my advanced training class, which consisted of six Aviation Midshipmen, had arrived at Cabaniss Field, Corpus Christi, Texas, at the first of September, we expected to be flying Turkeys (TBMS) and training to be attack pilots. The only consolation we had was that at least we were going to be flying single-engine aircraft and not the PBM flying boats at Mainside to which some of our former classmates had been assigned. We used to kid them by saying the PBM took off, cruised, and landed at 70 knots. Of course, all they had to do was grin at us and go "Gobble, gobble, gobble!" Those others who were going to fly fighters had gone to training units at Cabaniss Field which were flying F4U-4s.

We spent the first month in ground school studying Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines and other subjects. I remember one day in Engines class, I could see out the window that Corsairs were taking off on runway 31 about every 30 seconds. After one of them took off, all of a sudden the temperature dropped about 20 degrees and it seemed that within 30 seconds a Corsair landed on the same runway headed in the opposite direction. The weather was that changeable in that part of Texas.

About the time we finished the month of ground school, without any warning, all the Turkeys disappeared and were replaced by Corsairs. So our training to be attack pilots was in F4U-4s! The attack pilot syllabus was similar to the one for fighter pilots except there was a difference in emphasis. We practiced gunnery, but not as much as they did. They practiced bombing, but not as much as we did.

The Corsair was fine for glide bombing using up to a 45-degree dive [comment from Ted Wilbur – “Not true. We did 70° dive bombing in the F4U with the landing gear extended – it acted as dive breaks.”]. But of course it could not do true dive bombing. Real dive bombing involves dive angles of 60 degrees or more, because it did not have dive brakes to control its speed in the dive. We had to wait until we arrived in the fleet and got AD-4 Skyraiders to practice true dive bombing.

The second unforgettable flight in a Corsair came on my second hop just the next day. It seems that as I was taxiing out for takeoff someone in the tower had noticed that my tail wheel hydraulic strut appeared to be low. I had not noticed it when I did my pre-flight check. At any rate, he did not mention it until after takeoff. Then the tower called and instructed me to land at once and to make a "wheels" (two point) landing to avoid any problem with the tail wheel. I had about 200 hours in SNjs during which I had done my best to make perfect three-point landings. I had never made a wheels landing on purpose in my life. Furthermore, we had been warned about the Corsair's tendency to porpoise during wheel landings. We were told never to try to stop the porpoising by chasing it – rather to keep the stick still and let the plane correct itself.

So following the established emergency procedures I told the tower I was climbing to 6000 feet to test the slow flight characteristics and then would make a wheels landing. After the slow flight test the tower cleared me in and sure enough old "Hose nose" started porpoising. But I let it correct itself, and the result was "an excellent landing." It has been said that a good landing is one you can walk away from; an excellent landing is one in which the aircraft can be used again. I know the plane was used again, because I flew it the next day with no problems.

So following the established emergency procedures I told the tower I was climbing to 6000 feet to test the slow flight characteristics and then would make a wheels landing. After the slow flight test the tower cleared me in and sure enough old "Hose nose" started porpoising. But I let it correct itself, and the result was "an excellent landing." It has been said that a good landing is one you can walk away from; an excellent landing is one in which the aircraft can be used again. I know the plane was used again, because I flew it the next day with no problems.

The rest of my time in the Corsair at Cabaniss Field was uneventful except for one hop at an outlying field where we were shooting dead-stick touch and go landings – three-point I might add! The instructor, Ltjg Bill Youmans, had landed and set up at the end of the runway with a portable radio.

Our class then took turns in a "round-robin" landing, adding power and taking off again, picking up our landing gear as we did. Each time around as we got to the end of the downwind leg and started our turning approach, we went over our check-off list and reported to the instructor, "Gear down, flaps down, check-off list complete, sit" and pulled off the power. At the end of the period, when I came around for my last approach, the instructor, instead of giving me a "Roger" with the LSO paddles as I expected, gave me a wave-off and then waved to all of us good-bye meaning we were going home. When I got back to the ready room he was already here, having landed first. As I walked in, he grinned and said to me "Gear down, flaps down, check-off list complete, sir." And that was the first time it dawned on me that I had made a wheels up pass! I never made another one.

My next adventure came in Advanced Carrier Qualification Training which was conducted out of Corry Field, Pensacola, Florida. Our field carrier landing practice (FCLP) was conducted at one of the out-lying fields the paved area of which was perfectly circular. So the alignment of the "flight deck" could always be into the wind. Because of the tremendous torque from the 2000-horsepower R-20OO engine and the four-bladed prop, a considerable amount of right rudder was necessary on takeoff. FCLP was conducted much the same way as ordinary touch-and-go landing practice, except that the landing gear and flaps were left down all the time and, during the approach, the pilot was under the direction of the Landing Signal Officer (LSO). As soon as we got the cut we would add power, raise the tail, takeoff, and go around to land again. Well; on one occasion, when I added power and raised the tail, with plenty of right rudder, to my amazement the plane asserted itself and abruptly turned at least 45 degrees to the left. I had no choice but to takeoff in that new direction. As I look back over my training jacket, I see no mention of that incident. I guess the LSO never knew it happened, because his back was to me as he brought in the next plane. But I remember at the time figuring out what had happened. It was a case of gyro-scopic precession.

When the axis of a gyroscope is rotated the gyro attempts to make the plane of the rotation of the axis become the new plane of rotation for the gyro. I had evidently raised my tail too abruptly as I added power and the massive propeller acted as a gyroscope. It tried to rotate in the plane of the F4U's rotation causing the F4U to abruptly turn to the left. I never heard of that happening again. But perhaps it has. At any rate, if I had not been on a circular field, I would have been a goner!

Another little adventure happened during FCLP. On one hop I had great difficulty in getting the F4U slow enough. Which meant that I wasn't getting sufficiently "cocked up." When you are flying carrier approaches in a piston-engined plane you do not look at your instruments, you keep your eyes on the LSO and observe the plane's attitude with your peripheral vision. You control your speed with your attitude; you control altitude with your throttle. After the flight was over, I discovered that the normally included cushion was missing from the seat-pack parachute. That had caused me to sit lower in the cockpit than I was used to and thus the plane seemed to be more "cocked up" than it really was.

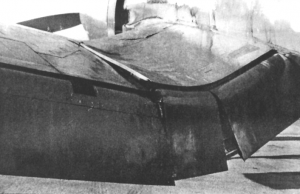

The hairiest adventure, at least while it was happening, took place on 23 February 1950, the day before my 21st birthday. It occurred as a result of the fact that the last duty a Corsair would be assigned to would be the Carrier Qualification Training Unit. Instead of undergoing the stress of landing once for every hour or two of flight time those planes would undergo it several times an hour, day in, day out, week in, week out. Add to that the fact that carrier landings are, if any thing, even harder on a plane than ordinary field landings. After months of that kind of abuse, a plane was not fit for anything else. Well, on one FCLP hop, after a normal landing, when I added power and took off I discovered I couldn't trim my ailerons and I couldn't pick up the flaps. The plane wanted to roll to the right. It took all I could do to keep the wings level. I looked out at my right wing and discovered that the entire outer panel, from the gull to the tip, had several extra degrees of attack! The spar had actually twisted as a result of metal fatigue and failure.

Once again the standard emergency procedure called for me to climb to 6000 feet and test the slow flight characteristics before I tried to land. But this time, I had an extra and frightening problem. Another rule said that during FCLP you kept your parachute leg straps unhooked to allow you to get out quickly in case of a crash, on the assumption you would be so low you would not be able to use the chute. If I was going to climb to altitude in a plane with a wing about to come off, I certainly wanted my parachute leg straps fastened! But since I could not trim the plane, I had to keep one hand on the stick. And it took two hands to fasten the leg straps. So I called the tower, explained my situation, and got permission to land at once without testing the slow flight characteristics.

"Oh, and by the way," said the tower, "make a wheels landing." Well, I did, and sure enough it porpoised a little and I let the plane correct itself, but this one turned out to be only a "good landing." I walked away, but the plane, F4U-4 Bureau Number 81305, was stricken from the books.

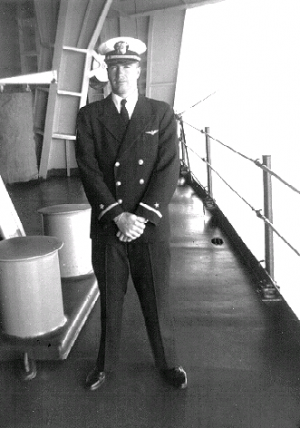

My last scrape in the F4U occurred on the "Ides of March" (the 15th), 1950, during carrier qualifications on the USS Cabot. The last thing each single engine pilot had to do in order to graduate from Naval flight training and receive his wings as a "designated Naval Aviator" was to make seven successful carrier landings. A flight of students would fly out to the carrier, land and takeoff seven times in "round robin," and then fly back to Corry Field. The LSO always kept a notebook on every pilot's landings. Normally, he debriefed pilots afterwards to give them a chance to learn from their mistakes. But in the case of carrier qualifi-

cations since you flew back to the shore and then graduated the next day, there was no opportunity for that. So I did not know what the LSO had written about my performance. I did know, however, that I had gotten one wave-off.

The next day I got my wings and went to Norfolk to await assignment to a squadron. I was assigned to VA-15, NAS Jacksonville, Florida, where I flew AD-4s. Three months later, in June, I received my commission as an Ensign, USN. The Korean War started that same month. A number of us junior pilots from VA-15 were transferred to VA-35 on the USS Leyte (CV-32), which had been rushed back from a cruise in the Mediterranean to go through the Panama Canal to Korea.

Some time later a friend gave me a photo which had been taken of that wave-off. On the back of that photo was written: Dick Cantrell 15 March 1950 Advance Carrier Qualification in Gulf of Mexico aboard USS Cabot. "Close Wave-off."

Note absence of background screen and Landing Signal Officer who was probably in mid-air at this moment in attempt to save his life. DNKUA