Section 1 – Early Years

Personal History

Lou was born on the Ives of March 1928. He grew up, attended grammar and high school in Alhambra, California, and matriculated at Southern Cal at age 16.

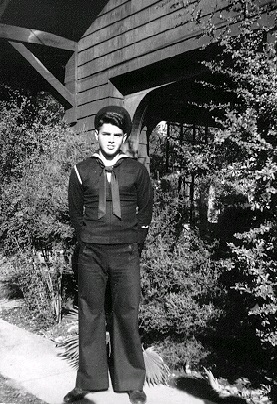

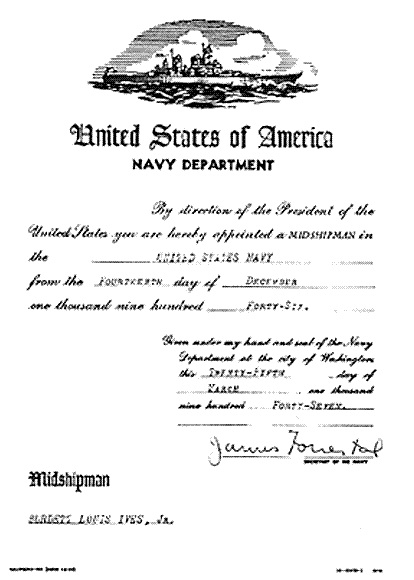

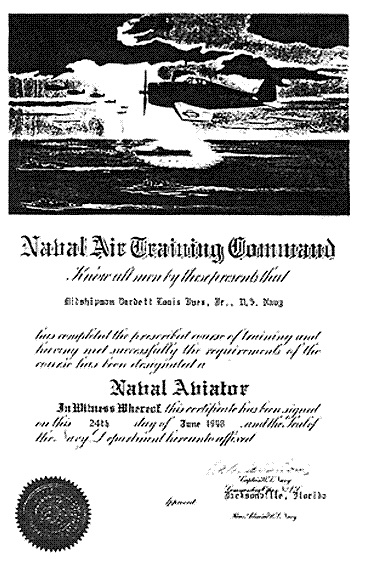

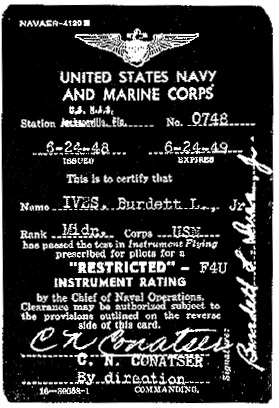

He joined the Navy V-5 Program in June 1945 as Apprentice Seaman, fleeted up to Aviation Cadet in June 1946, Aviation Midshipman in December 1946, got his wings as Aviation Midshipman, USN, in June 1948. In December 1948, during a tour in Hawaii with VA-213 flying TBMs, he received his commission as Ensign, USN.

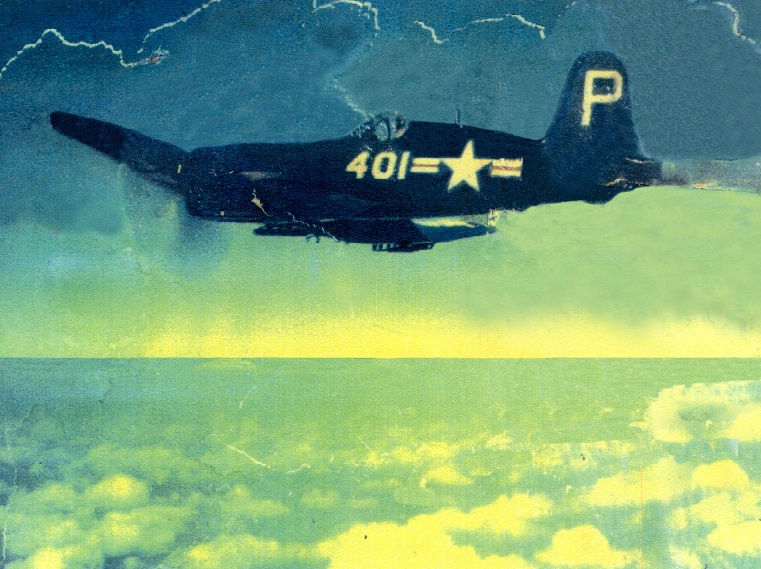

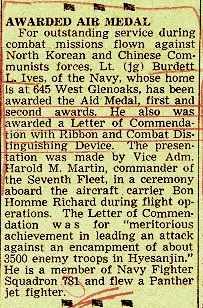

During a tour with VA-134 flying F4Us, Harry Truman and Omar Bradley conspired to give him $300 and kick him out in December 1949. Their timing was bad – the Korean Fracas started in June 1950. Recalled from flying F6Fs in the Reserve, Lou joined VF-781 at San Diego flying F4Us and F9Fs. 1950-1953, he made two tours with the squadron on the USS Bon Homme Richard (CV-31) and the USS Oriskany (CV-34) with Task Force 77 in Korea.

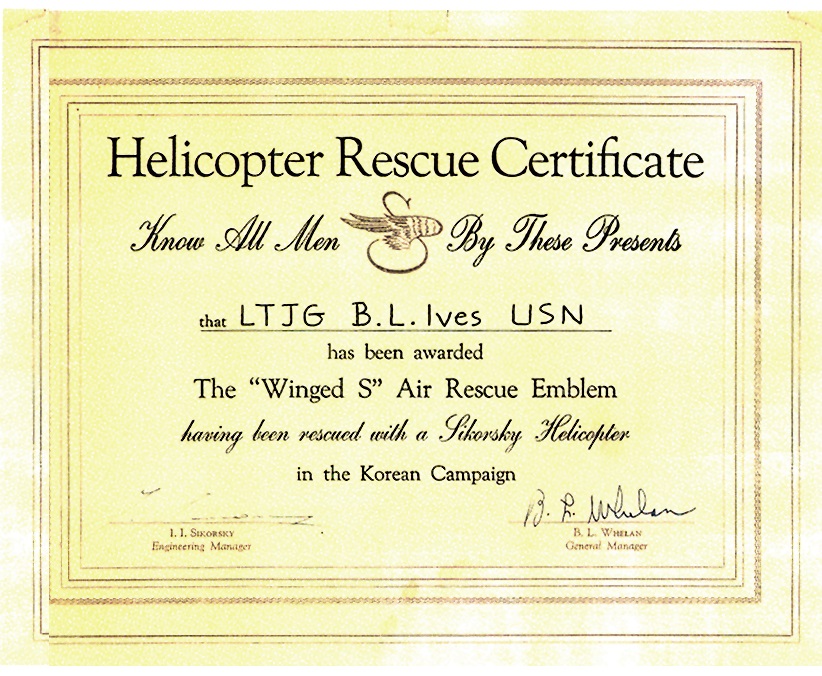

He flew 129 combat hops over North Korea, mostly deep fighter reconnaissance, flak suppression, and combat air patrol. Shot both ways – up 6, down 2; ditched twice – once in the Sea of Japan and the other in Wonsan Harbor.

Lou left active duty in July 31,1953, and stayed in the Reserve until 1959, flying F2Hs, F9Fs, and HUPs at Los Alamitos and Oakland. Had 2,000 flight hours, 189 carrier landings, and 5 cargo ship landings (in HUPs).

He was one of the pioneers (1955-1965) in the commercial helicopter industry, flying Bell 47s in Central California doing powerline patrol, fire fighting, construction sling-load, and agriculture. Got another 2,000 flight hours.

That was the fun part.

Lou received his only degree (MBA) from University of Virginia’s Graduate Business School in 1967 at age 39 (after six undergraduate schools – with no degree) – 23 years between matriculation and graduation.

Thereafter, followed 30 years mundane work in management and con-sulting – mostly in small companies. He is currently consulting in small business in the Virginia Piedmont area.

Lou, in collaboration with his colleague, Patricia B. Francis, is a researcher and correspondent for VF-781 PACEMAKERS HISTORY and THE BROWN SHOES – a collection of personal narratives, photographs, military documents, newspaper and magazine articles, audio and video tapes, and other memorabilia submitted by the great guys who went through flight training between 1946 and 1953. In May 1996, he and Pat Francis donated twenty-four 100 page hard copy volumes of the Flying Midshipmen History (now titled The Brown Shoes – Personal Histories of Flying Midshipmen and Other Naval Aviators of the Korean War Era©); thereafter, three hard copy volumes of the VF-781 – Pacemakers History to the Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, PNS [Pensacola, Florida]. The completed VF-781 PACEMAKERS HISTORY and BROWN SHOES HISTORY will be available on CD.

Section 2 – TRAINING and PRE-FLIGHT

The Beginning

[Log of Lou Ives’ entry into the Navy.

Resurrected from a holographic log damaged in his 12/30/90 house fire]

USN

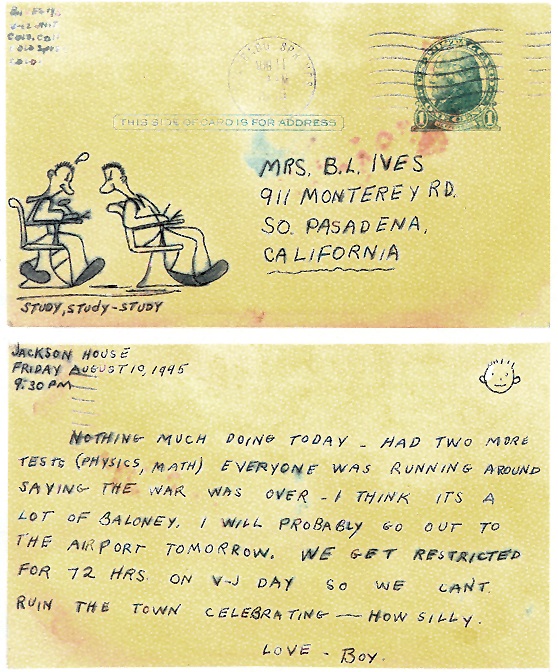

TUES MAY 15, 1945 – Got word from Jack Dunkle that V-5 was open.

WED MAY 16, 1945 – 1:00 pm went down to 411 5th LA. to Navy recruiting office – signed up – took first eye test with B. C.[Bob Crosby] and R. W. [Reid Willis].

TUES MAY 22, 1945 – 11:00 pm received word that Navy had called at 4:00 and to come down next morning.

WED MAY 23, 1945 – 9:00 am got up and got to NOP [Navy Officer Procurement] by 10:00 – told to come back at 1:00 for test – 1:00 took C-3 test – It was a bitch; coasted through first pages of math. What an amazing concoction of problems – also took MTC [?] test passed – told to return at 8:30 next morning.

THUR MAY 24, ‘45 – 8:30 am – took ATC – passed with B. After test – went into cdr’s office for interview then phys – came out o.k. – 3 of 40 passed – given some papers to get call transc.

FRI -

MON MAY 28 – went to AHS [Alhambra High School] for transcript – going back tomorrow to get it.

Tue. May 29 – received coll. transcript – went to AHS and got High School transcript.

Wed. May 30 – father gave me consent – received B. C. everything ok – three pictures.

Thur. May 31 – went to DNOPLA [Director Navy Officer Procurement Los Angeles] and gave papers in – o.k. – had final interview – I think I am out – maybe.

Fri. June 8, got letter from DNOPLA. Said to come down for final interviews – processing.

Sat June 9, went to Navy, had interviews – more fingerprints – Tue. sign papers and cards galore, took oath at 12:10.

June 19, went down with B. C. he is not out yet. to get orders about before July 1, have to report 6-1 [sic: should be 7-1].

Wed. June 27 (Arrowhead Calif) learned from B. C. that orders had arrived – B. C. sworn in & is going to C. C. [Colorado College V-5] phoned home, I am going to C. C. too.

Sat June 30, (9:30 am) reported to DNOPLA for 10 min & got orders & ticket requests. Rushed around all day seeing people & getting ready.

Still June 30 4:30 pm got to U. S. with folks and B. C. met 13 other guys. 4:50 went to H.H. [station restaurant] to eat. 5:00 eat until 5:30. Saw folks again. Gathered at S. P. [Southern Pacific] and herded on train. 6:40 left L. A.

8:10 Pamona

9:00 Riverside

9:45 Berdo

11:30 Barstow

5:45 [Am] Las Vegas

1Burdett L. Ives: Colorado College V-5 – three semesters June 1945 – June 1946. Compiled 29 semesters, January 1994.

Colorado College V-5

(three semesters June 1945-June 1946)

[Background: a 1996 request for V-5 information from Colorado College]

(I. Relate a particular V-5 experience that stands out):

Colorado College didn't have a great football team in the 1945 season. One afternoon CC played another team from somewhere – I think that team made the following New Year's Sun Bowl. The other team ate our lunch. After the game, a fight started on the field – emptied the stands. Our V-12 Marines and Fleet Navy wound the others’ (mostly 10th Mountain Division) clocks.

The Army MPs from Camp Carson entered the fray and billy-clubbed the hell out of one of our Marines. The next day our Marine skipper summoned the Army MP skipper, braced him in front of the Marine office, and tore a large meaningful strip off his butt that that must have smarted for a couple of months: "Your people don't hit my people. No one hits my people."

This demonstration of Marine loyalty impressed the young 17-year-old me. Since then I have had a deep feeling for the link of loyalty and Marines. This impression continued with me to Korea – and five battle stars (1951-1953) flying deep fighter recco. I felt that any bad guy I could keep from reaching the MLR, maybe one Marine would get back home. Preaching this, I was shot both ways – up six, down two. Hopefully, I helped a couple more Marine mudsloggers get home. Tell your Marines that the Navy gives out purple hearts, too.

I learned a lot more at CC than the school transcript shows, thanks to you Marines.

*****

The last semester (1946) we were billeted on the top deck of Hagerman Hall. One frozen night, after a bit of beer on the town, our guy eyeballed out of the 3rd deck window and saw the Skipper's car parked below. While we all looked on, he proceeded to urinate three floors onto the top of this auto.

We all laughed and rolled uproariously. We forgot one thing: the temperature was below freezing.

The next morning the Skipper eyeballed the frozen glom on his roof, eyeballed the third deck window, and the entire third deck did a lot of heel-and-toe. A lot.

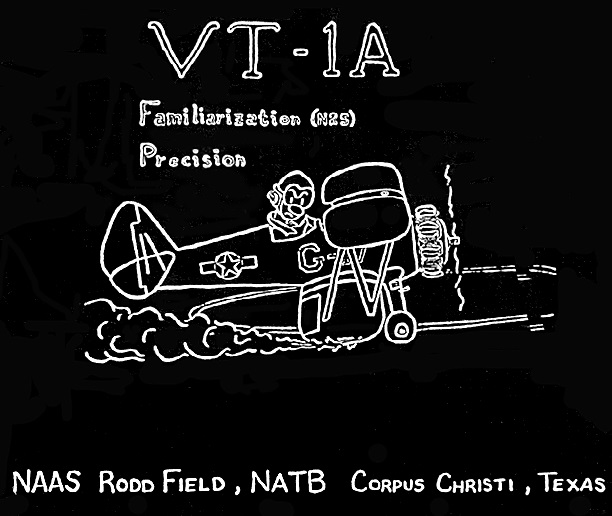

ON FIRST FLIGHTS AND FAM HOPS

NAS Livermore, California. Livermore is in the first agricultural valley east of Oakland. Another range of hills separates Livermore Valley from the great San Joaquin Valley.

We had finished all the chores that accompany fleeting up to aviation cadets from V-5 apprentice seamen, gassed the big blue fighters for a week, attended the required ground schools, and, on June 26, 1946, were ready to get our first familiarization flight in the Stearman N2S-2.

We got to the hangar, checked the schedule board, drew parachutes, and went out to the flight line to man our aircraft. Most instructors were at their scheduled aircraft to greet the students. Mine wasn't in sight.

I preflighted the machine (N2S-3 BuNo 07931), finished strapping on the chute, climbed into the aft cockpit, cinched the safety belt and shoulder straps, and waited. And waited. No instructor. All other planes on this hop had by now departed the flight line and were taking off from the mat. Not me.

About 15 minutes later the instructor arrived – a short, wiry, red-headed guy [LT B. N. Battino]. He climbed in, plugged in the gosport tube, made a few casual comments, taxied out, and we were off to check out the area and the aircraft.

We climbed to altitude (about 3,000 feet) and drove around the area doing things people do on their fam hops. The instructor noticed smoke from a burning grain field and headed for it. He circled, watching a half-dozen people trying to beat down the flames with gunny sacks and shirts.

Enough of this! We hep those guys! The instructor brought the Yellowbird about, slipped to a landing in an unburned portion of the field, taxied to the flame line, did a 180, set the brakes, and added throttle to blow the fire out.

This maneuver touched off a raging inferno in the grain field. Unmiffed, the instructor told me to hold the brakes while he got out to help the farmers beat back the flames.

So here is this 18-year old student on his first hop, sitting in a machine made of burlap and bailing wire, holding the brakes with the engine ticking over, watching a not-too-successful attempt by several people to beat out a well-involved grain fire. About 50 feet aft and closing.

After a bit, the instructor got his marbles together, walked back, and climbed into the machine, waved good-luck to the farmers, took off (obviously down wind) and, since the period was over, flew back to Livermore.

So much for Fam Hops.

NAS Livermore, California

N2S-3 (BuNo 07931)

5 hours 15 minutes dual

15 minutes solo

3 July 1946

Ottumwa, Iowa Pre-Flight

Champions Class 9-46, Batt. 1

Wings 24 June 1948

Commission 14 December 1948

WINGS at JAX 24 June 1948

Alan E. Beck (9-46) Charles W. Stephens (4-46)

9331 Greenbriar Drive P.O. Box 1824

Orinda, CA 94563-6824 Baton Rouge, LA 70815

Thomas E. Davis (9-46) Robert L. McIntyre (4-46)

P.O. Box 2050 1565 Mission Bend Drive

Crystal River, FL 32629 Brownsville, TX 78521

Stuart E. Ferguson (9-46) John R. Nicholas (10-46)

1520 Barton Drive 22 Cape Cod

Sunnyvale, CA 94087 Irvine, CA 92720-2711

Archie Hood (10-46) Charles W. Stephens

2112 Bois De Arc Circle 9331 Greenbriar Drive

Norman, OK 73071 (6-23-48) Baton Rouge, LA 70815

Burdett L. (Lou) Ives (9-46) Tom Vorhees (-46)

1109 Fox Ridge P.O. Box 1107

Earlysville, VA 22936 Bigfork, MT 59911 (6-23-48)

Donald E. Luallin (9-46) Roy D. Murphy (10-46)

401 100th Avenue, NE (#210) 169 Pearl Avenue

Bellevue, WA 98004 (6-23-48) Tavernier, FL

William D. Maddinger (11-46) Louis C. Potter (11-46)

6309 South Aia Way (6-23-48)

Melbourne Beach, FL 32951-2718 (6-23-48)

Charles W. Stephens (4-46)

9331 Greenbriar Drive P.O. Box 1824

Orinda, CA 94563-6824 Baton Rouge, LA 70815

Robert L. McIntyre (4-46)

P.O. Box 2050 1565 Mission Bend Drive

Crystal River, FL 32629 Brownsville, TX 78521

Stuart E. Ferguson (9-46) John R. Nicholas (10-46)

1520 Barton Drive 22 Cape Cod

Sunnyvale, CA 94087 Irvine, CA 92720-2711

Archie Hood (10-46) Charles W. Stephens

2112 Bois De Arc Circle 9331 Greenbriar Drive

Norman, OK 73071 (6-23-48) Baton Rouge, LA 70815

Burdett L. (Lou) Ives (9-46) Tom Vorhees (-46)

1109 Fox Ridge P.O. Box 1107

Earlysville, VA 22936 Bigfork, MT 59911 (6-23-48)

Donald E. Luallin (9-46) Roy D. Murphy (10-46)

401 100th Avenue, NE (#210) 169 Pearl Avenue

Bellevue, WA 98004 (6-23-48) Tavernier, FL

William D. Maddinger (11-46) Louis C. Potter (11-46)

6309 South Aia Way (6-23-48)

Melbourne Beach, FL 32951-2718 (6-23-48)

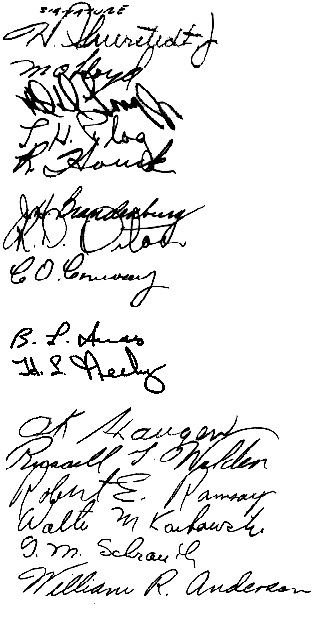

C. 0. M. Statement

VA-213

STATEMENT AS OF 8 MARCH 1949

ASSETS: Cash on hand $76.86

Inventory 00.00

Total worth $76.86

Value of mess, share, 16 members @ $4.80 each.

I hereby certify that the balance sheet and statement of income and expense herewith are in agreement with the books of account and records of the Commissioned Officers' Mess of Attack Squadron TWO HUNDRED THIRTEEN, of which I am treasurer, and to the best of my knowledge and belief are correct.

/s/ Burdett L. Ives, Jr.

Treasurer

VA-213, NAS Seattle, Washington, March 9,1949.

AIR GROUP 21 – ALL WEATHER AIR GROUP:

VF-211 – 12 F6F-5Ns, VF-212 – 12 F6F-5Ns,

VA-213 – 12 TBM-3Ns, VA-214 – 12 TBM-3Ns

MARCH, 1949, Roster of Attack Squadron 213 (VA 213):

"Received of ENS B. L. IVES $4.80 this date."

Date Name

3/8/49 LCDR H. Suerstedt Jr.

3/8/49 LT M. 0. Lloyd

3/8/49 LT D. D. Long

3/8/49 LTJG L. H. Plog

3/8/49 LTJG R. Houck

3/8/49 LTJG J. H. Brandenburg

3/8/49 ENS R. D. Orton

3/8/49 ENS C. O. Conway

3/8/49 ENS* B. L. Ives, Jr. [0496290]

3/8/49 ENS* H. L. Neely [0496307]

3/8/49 ENS* O. K. Haugen

3/8/49 ENS* R. G. Walden

3/8/49 ENS* R. E. Ramsay

3/8/49 ENS* W. M. Karbowski [0496455]

3/8/49 ENS* G. M. Schrauth 3/8/49 ENS* W. R. Anderson [0496906]

3/8/49 ENS* W. R. Anderson

*These ENS all joined the squadron as Aviation Midshipmen in October 1948.

From the 9 MAR 1949 VA-213 liquidating Squadron Mess statement:

ENS B. L. IVES, Treasurer (all members are assumed to have signed)

(furnished by Lou Ives 9-46, 4 APR 1991)

Pre-Flight

I was in Class 9-46 at NAS Ottumwa, Iowa.

In September, we were a bunch of AvCads at NAS Ottumwa, Iowa, having completed the syllabi from various V-5 colleges and such E-bases as Glenview, Livermore, and others. By September, Ottumwa was the only [and these are my tentative thoughts] Pre-Flight extant; St. Mary's and the others having been closed.

By the time 9-46 was formed, 3-46 had been sent to Corpus for Primary in N2Ss and 5-46 was ready to go. 9-46, the soon-to-be Senior Class, was scheduled for a 16-week Pre-Flight with Corpus primary gleaming around the first of '47.

Sometime in the fall, 9-46 was suddenly no longer Senior Troop. 5-46, and I believe, 3-46 for a while, returned to Ottumwa from Corpus. Pre-Flight was extended to 6 months, classes in metallurgy and history were begun. It was close to this time that we began to sense an inkling of 'Regular Navy'.

Shortly after, 9-46 and 10-46 were polled for the feasibility of USN AvCads in the postwar Navy.

Later, probably in December, we (at Ottumwa) were mustered in the auditorium, and [I believe] Captain Jeter and Admiral Holloway in a gung-ho hour presented the prospective Aviation Midshipman program.

Whatever the date, we were all given the choice of remaining AvCad, USNR, or going AVMID’N, USN. I am not sure of the ratio, but an overwhelming batch chose to go AVMID’N.

[We went through the program with both persuasions, some getting wings as ENS, AVH, USNR; and others as MID’N, AVH (later 1310), USN. Our class-mates also consisted of the last Marine and Navy AP enlisted pilots.]

In any event, most of us chose The Program, and were sworn in as Aviation Midshipmen on December 14, 1946. By this time, both classes 3-46 and 5-46 had returned to Corpus, and 9-46 was again King of the Campus at Ottumwa.

But then funny thing happened – an inkling of how screwed up the Midshipman program was to get. Class 9-46 got the low file numbers. I believe Dean Webster was the lowest; mine was 496290. Others at Ottumwa were in the same range; while the senior classes 4-46 at Corpus and Pensy had higher file numbers. Bad.

And still another funny thing happened. About March, 1947, as we were about to graduate from the 6-month program, the Pre-Flight syllabus was short-ened to the original three months. 9-46 was the only class in Naval history to endure 6 months of Pre-Flight.

But things got worse for the Midshipmen. No one (at Ottumwa) bothered to tell us that we were to buy our own clothes, ship our own baggage, and tend our own horses.

The AvCads had all the rights and privileges of enlisted troops; the midshipmen had neither the rights nor privileges of the enlisted or the officered. One hell of a shock for The Believers at $75 (?)/per. And no flight pay.

Whatever.

AVMID'N USN and ENS USNR served side-by-side, Atlantic and Pacific. (I was in Pacific torpeckers). About December, 1948, the original Midshipmen were commissioned ENS USN, to date from (and perhaps after) the Academy class of 1948. (And two years in pay grade behind those who chose to remain AVCAD USNR).

I was commissioned in December '48 at Barber's Point. Captain Paul Ramsey gave me the oath in his private office. I hope he didn't smell me – I was so loose I got an 18 on my Snyder. No one knew what the drill was, but everyone tried his best to get the job done by the 31st – or my date of rank would have been in June 1949, as things are wont to be done in the Navy.

Meanwhile, this is how I started (probably descriptive of all of us):

In March, 1945, after a semester at Southern Cal, several of us turned 17 and heard the clarion call of The Service. (nothing else to do – there was a war going on).

A few went to the Los Angeles Navy office next to Pershing Square ["Join the Navy and be with MEN”].

Anyhow, Bob Neely (Harold L.), a guy named Morrison, and I, from our batch of 250, were selected in May of 1945.

June 8th, 1945, a bunch of us took the oath in Los Angeles, and, with a short-term outlook on life, awaited orders.

In July 1945, we reported at the Los Angeles Railway Station. 48 hours later, Neely, Ives, and a dozen others (without Morrison), debarked in Colorado Springs to encounter three semesters of V-5 at Colorado College.

In June 1946, after three semesters, (we were now qualified college juniors at age 18), Bob Neely and I were shipped to E base at Livermore, California. I was first in the class to solo – after 5 hops. (it took me forty years to reason as the instructor did – If he could solo me on July 3rd, he could get the 4th and a bunch of days off. He did, I didn't crash, and he got his bunch of days off).

Regardless, we went from there to Iowa Pre-Flight (St. Mary's may have been closed, but a couple of our Colorado people had gone there), arriving sometime in August 1946, forming Pre-Flight Class 9-46, the original if not the senior AVMID’N class.

The AVMID’N group is unique in Naval history – an above-average group that encompasses not only the aviation history from the end of WW II through Nam, but also both the public and private sector during the same period.

SAN to JAX

Memorable Experience:

Early 1949: Taking off in an 18-plane “V” from the round mat at North Island. F4Us. VA-134 Hellrazors. Air Group 13 was trans-ferring from SAN to JAX. The Skipper (Sam Walls) stood up in the cockpit at the head of the “V” and, in best John Wayne style, waved his arm, “Hoooo!” I was half way down the right echelon. My entire thought was, “If anybody blows a tire, this will turn into my most humorous experience.”

Humorous Experience:

Re the above episode: I (as boot ensign) was supposed to drive my auto to JAX and Bob Neely was supposed to fly. After a couple of pops at Building “I” he commented upon the flimsiness of the walls of the BOQ. I drew an “X” on the wall and told him to put his fist through it. He put his fist in as far as the stud. Broke his hand.

Bob Neely drove my auto to JAX and I flew his F4U Hog Machine.

Footnote (#l):

After waking the base medical officer (about midnight) and listening to his miserable comments while he dressed Bob's hand, we all departed to the sack. Many moons later, Bob found the entry in his medical jacket: “Injury resulting from organized athletics.” Both Bob and I would like to find and thank that guy.

Footnote (#2):

Driving Ives’ 1946 Chevy coupe, Bob stopped in Tallahassee to visit with Danella Goff, whom he had met and to whom he had promised marriage a year earlier – while training in F6s at JAX. He did. She did. They were married in the JAX chapel on May 26, 1949. Lou Ives was best man.

And that is another story re: the Chaplain’s hat.

An F4U Story

1949-JAX – We were a bunch of Ensigns when we were sent to NAS Quonset Point to pick up some Hogs as replacements for our squadron (VA-134).

So we picked up 9 of these things to fly back to our squadron. We flew them down and refueled at NAS Norfolk. The weather was quite crummy but our leader, a senior ENS, said we would press on. The weather was REALLY crummy as we headed south. It was getting dark. The senior ENS lost track of where the hell he was (i.e. he got his ass p clp class=br /ass=br /lost). I checked my fuel gauge – it was pretty low. We started circling (whatever it was or where I was circling I had no idea).

Suddenly, my division of four aircraft flew through another division of five aircraft (the navigation lights told us so).

I took the initiative and found a field – NAS Glynco – a blimp base – no runway lights (blimps land on mats). I called; they lighted up the round mat. Inasmuch as the circle of lights around the 2000 foot diameter map didn’t tell me anything, I called the civilian field and they cleared me to land on their active runway. As I came over a large building, I got a horrible sinking feeling. I cut the throttle and landed with lots of sparks. My hydraulic system had failed – flaps had come down and the machine slid to a stop on propeller and flaps. I called up the flight and said, “good news, I’m on the deck.” And I said, “bad news, your runway’s blocked.”

My fault – my fault. I not really stupid – I can stand as straight as anyone.

I slid to a stop on the duty runway – everyone else landed on a crosswind runway except for George who attempted to put down on an unlit Blimp Base. The tower contacted the rest of the flight. Except for George Schrauth. All landed cross wind at New Brunswick Airport, all were O. K. George tried to land at the Glenco Blimp Base and without lights, hit the dirt, and flipped over.

We went out and drank a lot of whiskey that night – didn’t do a bit of good.

Early the next morning, I went out to my airplane that was wheels up on the runway. There were a bunch of Navy guys trying to salvage the sucker. The salvation people were trying to put a rope around the tail to drag it off the runway.

“Put a rope around the prop hub and drag it that way because that’s the way the thing works,” sez I.

Sez they, “you’re dumb.”

I insisted on my way. They hauled it off with no more damage.

In F4Us, a hydraulic failure will drop the tail wheel. The only damage was a bent prop and some skidded flaps – that’s nothing.

Section 3 – on the USS bon homme richard (cv-31)

1951

UNITED STATES PACIFIC FLEET

AIR FORCE

FIGHTER SQUADRON SEVEN EIGHT ONE

C/O FLEET POST OFFICE

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

10 May 1951

We shoved off from the quaywall at exactly 1000, the only time the ship, to my knowledge, had done anything on schedule. There were no bands, dancing girls or fireboats throwing water into the air, only a small but loyal gathering of families and girl friends waving forlornly as we sailed off to patrol our beats for The Greatest Sheriff Of Them All in his latest police action. Even Bob Fleming's boy Bobbie wanted his old man to hurry up and leave so he could go back to the bed from which he was so rudely awakened at five o'clock to see his papa off. In fact, the only celebration of any kind was when some of the pilots of the squadron sang Aloha Oh and threw confetti and leis over the side as we got under way; and the tugboats' one blast on their whistles as they shoved off to leave us alone against the elements – a demothballed ship with a demothballed air group. We were glad to go, hoping that our sins would blow over before we got back and happy that they hadn't caught up with us before we left.

When we got far enough away from the dock for our faces to become indistinguishable, almost all hands went below to the wardroom for a cup of coffee and the perennial card game. Very few stayed on deck to watch Point Loma slide past for what would probably be their last look at the States. Nobody gave a damn.

As soon as we cleared the jetties off Point Loma, we caught the ground swells, and as the wind was fairly strong, piling the water up into five to ten foot waves, we began to pitch and roll; the effect of which was noticeable fairly early among the greener peas on board, including me.

When we got far enough off the coast to shed the California influence, the fog broke up and the day came forth clear and bright. But I didn't notice it much – the ship was still pitching and rolling. Jack Dewenter and I went out on deck after the evening movie, a rip snorter called "State Pen" which I had seen only three times before. The night was clear and the stars were out bright, but what amazed me was the new moon. It was so bright that it sent a reflection across the water as bright as the full moon does when it's shining through the smog back in California. And still the damn pitching and rolling.

UNITED STATES PACIFIC FLEET

AIR FORCE

FIGHTER SQUADRON SEVEN EIGHT ONE

C/O FLEET POST OFFICE

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

12 May 1951

I dreamed I was a prisoner of war Friday night – or was it Saturday night? I've lost track of time already. We got a bunch of lectures today which nobody wanted to give, attend, or would remember ten minutes after they were over. The only thing that interested me was that the Japanese type of V. D. is practically incurable.

The sea is deep blue with whitecaps and the sky is a brighter blue. We saw flying fish for the first time today. They surprised me. I used to think that they just jumped out of the water and that the flying part was just in some Hollywood advertiser's imagination, but they really fly – or sail – along. Some that I've seen have glided three to four hundred feet, sticking their tails into the sea every once in a while with a wiggling motion to keep up enough airspeed to sail on father. But I see none of these – still that goddamn pitching.

14 May 1951 – Monday

We can see the Hawaiian islands this morning. First we saw the peaks of Maui, then Molokai, then Oahu as we slipped past it into the waters south of the islands where we are due for three or four days of operating. The jets are scheduled to fly full load strikes against Kahoolawe, a small target island south of Maui today – if we can get enough wind across the deck to launch us with full ammo, six five inch rockets, and a full gas load (the gas load alone weighs 5200 pounds). The sea is perfectly calm and even with this bucket of bolts' 32 knots, it is advisable to augment this with a couple more knots of wind just to be on the safe side.

SAVE THESE LETTERS * I MIGHT WANT TO READ THEM LATER.

16 October 1951

Ready Room

We had a pretty good day today – we (Cran, Jim, Rick, and myself) were scheduled for a dawn launch to sweep some airfields in North East Korea that have been suspected by the higher wheels as being used by the CCAF for advanced bases or emergency fields for their night heckler flights. We didn't expect to find much, as the fields are in pretty shoddy condition. Our B-29s raid them every time they get them fixed up.

We got the dope last night that we were scheduled for the flight. We got together with some recent photographs of the areas and discussed our attacks and emergency procedure, then went to bed about 2130.

At 0430 the alarm rang, awakening everyone in the room because I had it on "loud". I dressed and went down to a hotcake and bacon breakfast then went up to the ready room to get into my gear. (The attached list is what I put on for this hop). At 0500 Bob MacPhail, our Air Intelligence Officer started his brief. He gave us all the dope on rescue facilities, target conditions (as well as he could), and flak positions. There wasn't supposed to be any flak on this hop but no one had been up there (35 mi. from the Tumen River) for quite some time, so no one knew the situation too well.

It was still dark when we manned our planes, although the full moon gave enough light to see by. The props, ADs and F4Us, were already turning up back aft in preparation to be launched against their various targets in North Korea. By the time they launched us it was light enough to see by, but I kept my cockpit lights on anyway. I didn't get too good of a shot off of the cat, and almost settled into the water, but by the time I got my wheels up and my canopy closed I was indicating 150 knots and joined up on Cran. His radio didn't work too well, so Jim took over the lead and Cran and I flew last section.

About 15 minutes from the target the ship called us and told us that a couple of the night fliers from the Antietam had a train corralled near where we were going, so they gave us the coordinates and vectored us over to it. We spotted one of their flares when we were still some distance to sea, and that gave us a good point to aim for. While we were still heading for the target, a flight of night hecklers from the Bon Homme made a couple of runs on it, but only had a couple of bombs left and didn't do much to it. The Antietam planes were reporting heavy flak from across the river and from the town of Tan'chon. We got to the target at 7000 feet and waited for the Antietam planes to make their final run. They had the locomotive steaming, but it was still in pretty good shape.

We peeled off and made our runs from out of the sun which was just rising in the east. Our first run was a strafing run off the loco and everyone was on good. (english good). We got a lot of steam from it on that pass, and pulled up craning our necks for the AA that was reported in the area. I finally saw them firing three automatic weapons from the east side of the bridge across the river on the Tan'chon side. They must have been 12.7 mm (.50 caliber) because we didn't see any puffs anywhere around. I guess the Antietam pilots are just as jumpy as we were when we were new out here. What they reported as "heavy, intense" we reported as "light, inaccurate" and paid no more attention to it. They would have to be damn good to hit anything at 7000 feet.

The next run was a rocket run and Jim straddled the engine, Cran put two short and two beside it, Rick put a couple in close, and although I made my smoothest run, I forgot to throw my rocket switch and couldn't fire. It didn't really matter, as we had all the time and gas we needed. We continued to make runs on the engine and 14 boxcars it was carrying, Jim exploded a boxcar with a 5" rocket hit, Rick hit the engine with a rocket, and claims that I did too, but I am pretty sure that all six of my rockets missed and that Cran was the one that hit it with the second one. (I can hit an outhouse six times out of six, but whenever a train comes along I'll miss it every time). We were strafing it all the time and had it pretty well steaming by the time we made our last couple of runs. I came in on a broadside run and slowed down to 300 knots. All of my guns were working and I got in close before I gave it three long bursts. For the first time in my life, I was on on the first. About 200 rounds of armor piercing, incendiary, and high ex-plosive 20 mm went right into the front end of the thing and steam started coming out from all over the place. I thought the damn thing had blown up and pulled about six “g”s trying to get out of the place. After that everyone got in one more good run and that engine won't go past many more stations (they are pretty good at scavenging and repairing so unless the engine actually blows up or is derailed, we can only list a "damaged").

We flew on up to check some of the fields we were assigned before we were vectored to the train. We couldn't see anything on them although we got down to 50 feet, so we gave up and came on home.

Cran was on the ship’s PA system tonight to tell of the deal, as they have an interview with some strike leader every night so the crew can get an idea of what goes on.

I’ve got to rush and get this in the 2000 mail or wait another week before it goes off.

/s/ me

9 November 1951

Hi there,

General Ridgeway came aboard today. He was aboard about four hours talking to Admiral Martin (Com 7th Flt), Admiral Jocko Clark (Com TF-77), and Captain Gill (CO BHR). Martin is off of the New Jersey and came over to the BHR by helicopter. More brass than you could shake a stick at. Ridgeway is both tough and competent looking. I only saw him for a minute, but I was impressed by his looks and attitude. He came into the ready room where several of the guys including the Skipper talked to him for several minutes. He watched a launch and landing, and as luck would have it, we probably had our best launch and landing while he was watching. Admiral Martin said that it was the best jet operations that he had ever seen. The General and his aides left for Korea by TBM transport. The two TBMs they were riding in were catapulted, and I bet they talk about that cat shot for a long time.

Thirteen more flying days until Christmas. Barring weather. We have had pretty good weather this November, so I imagine that we will fly most of them. All the jet pilots will get 60 hops in, and I have eight more to go for my 60. Most of the guys will be glad to get home. They gave us our choice of assignments when we get back to the States, and a surprising number of the guys put in to stay in 781 and take another tour of combat. I did. I can still get out, tho, and I might put in my quit chit in time to go to summer school at SC. That will have to wait until we get back.

I got up at 0400 yesterday for an 0630 – 0800 CAP hop. We were launched at 0630 when it was still fairly dark. The sun was not up yet and I had to turn on all my cockpit lights to see the gauges. We were to orbit the force at 20,000 feet in case any Commie planes started to snoop around. The weather was CAVU with a little cloud layer on the horizon. The sun came up over this cloud layer and made probably the most beautiful sunrise that I have seen in a long time. In the thin air of 20,000 feet, it appeared to rise rather quickly, being entirely visible in about 45 seconds. After it was up it was so bright that it hurt my eyes. Very pleasant hop.

Later I was standing in the ready room when the Duty Officer asked me if I wanted to fly another hop. I said yes, and three of us were launched with a full load of rockets and ammo to hit 5 locomotives in the city of Hungnam. The night fighter had found them just as the Commies were camouflaging them for the day, and destroyed the railroad track on either side of the trains so that they wouldn't go anywhere. When we got there the area was pretty messed up from previous flights but most of the locos were still good. It takes a lot to knock out a locomotive. We straffed them and got the satisfaction of seeing clouds of steam erupt from two of them. Also a lot of the supplies that they were carrying blew up in red flames. I got a near miss with one of my rockets, and much to my amazement, I got a direct hit with an ATAR [anti-tank rocket – one of the new ones that the Navy recently developed at lnyokem. It will go through 17" of armor and raises the temperature inside to 1500º F]. I watched the damn thing go right into the side of the boiler and the whole engine seemed to erupt in a large red-black flame (why that color, I don't know). It wasn't even steaming when we left it. Later the props went in and finished the job. It was probably the biggest transportation setback the Commies have had in a long time.

I caught a cold last night and am feeling punk today. We don't fly tomorrow, so I can stay in bed all day and loaf (as usual). I can't think of any more to say, so I'll write more later. Mail tomorrow.

/s/ me

Picked up flak over Yangdok – almost made it home

F9F-2

“I was horrified that the dozen girls and boys were to share the same cabin, albeit in separate room: not proper.”

1951

HEARD OVER THE RADIO

Airborne over the North Korean east coast in 1951, LTJG Lou Ives (VF-781) heard the following exchange over the gunfire net:

[Airborne gunfire spotter adjusting fire from a battleboat's 16" main battery on an inland bridge]:

Spotter: O.K., CALLSIGN, that last was about 500 feet short. Add 500 and fire when ready."

Battleboat: "On the way."

Spotter: "O.K., CALLSIGN, that was about 100 feet over."

Battleboat: "Shall I drop 100?”

Spotter: "No, never mind. The bridge is down."

Airborne over the North Korean east coast in 1951, LT Levi (Monty) Monteau (VF-781) heard the following on the emergency net:

[A Marine pilot had been hit badly and lost his engine. The aircraft was burning, and the panicked pilot, who couldn't open the canopy to bail out, was dominating the frequency, asking for help, describing his situation – in short, he was going in and couldn't get out of the aircraft – and, with his problems, he was denying anyone else the time and opportunity to assist him.]

Finally, when the pilot took a breath, an airborne South African voice was heard:

"Oye, say, Yoink, shut up and die like a man."

Silence from then on.

ON FIRST COMBAT HOPS

June 1951:

The Chinese had launched their spring offensive. The Bon Homme Richard (CV-31) – CVG-102 with VF-781 aboard – had made a dash from San Diego, through Pearl, and straight to the Operating Area.

Bypassing Japan, the Bon Homme pulled into TF-77 the afternoon of 31 May 1951, and sent in a jet recco of VFs and a prop strike of VFs and VAs. A Most Experienced Senior Guy came over from the Boxer to lead our recco into Indian Country. We launched him into the water (thank goodness he was flying his own machine). Things were pretty screwed up, but we’d look better the next day.

Next day. Dawn patrol. First hop. VF-781 two-plane recco. Burr Williams and Jake Holliman. Lou Ives as standby.

Flight Quarters! Pilots, man your planes! Standby to launch! Ives is standby. Fly 3 is motioning to Ives. Fly 2 maneuvers him to the cat. Full bore. Finger to the cat officer [we didn't salute in those days]. Gone.

Burr's machine busted. Jake Holliman and Lou Ives airborne on their first ever combat hop (a briefed recco from Kojo through Kumwha to Chorwon).

Lou called Jake to tell him that Burr was down, and he (Jake) had the lead. Jake called back and said that as Ives had replaced Burr, Ives had the lead. The argument, as to who was the leader, went on for several miles.

It was resolved by matching serial numbers. Jake was senior.

AIO Bob MacPhail had briefed us to hit the beach south of the recco route, as several flak batteries had been observed at Koto-ri. When we hit the beach, we had no idea where we were, so we circled until we got a fix from our charts.

After a few minutes, we were oriented. No problem. Right over that town on the small peninsula called Koto.

Heading south on the route:

Box cars. Firing at a siding of box cars – what targets! Filled the whole screen – as the gun camera film later showed. We later found out that Asian railroad cars were much smaller than the American railroad cars we knew as kids, and thus we were much closer than we had reckoned. We must have damn near rammed them.

People. As the two cherries razzed down the deck, pictures were taken of infantry. Jake was firing at one guy who filled the screen – looked a bit like Lee Marvin – couldn't hit the guy, but must have scared him some kind of loose.

Terrified the citizenry on down to Kumwha – the MLR was just south of the Kumwha-Chorwon Iron Triangle baseline. Neither the bad guys nor the good guys were about to expose themselves to us so we came on back, and departed for the Bon Homme.

Debrief:

“You mean that you went in at Koto-ri, flew down ‘Red Two,’ to Kumwha and Chorwon – the base anchors of the Iron Triangle – flew back the same route, expended all your ordnance – and didn't see flak?”

“No, were we supposed to?”

[Interestingly, Ives' last recco, in May 1953 – two years later – was over the identical route.]

Those gun camera films were quite entertaining in the ready room, as were the ones Lou Ives took on his next (second) recco north of Wonsan:

“Hey, Lou, what's that in the left-hand corner?”

“What left-hand corner?”

“Run that film back – let's see.”

Recrank, recrank.

“Damn, that's a powerline tower. See, the next tower is on the other side of the frame.”

“Yerch, Ives, the lines must have gone right across the top of this frame. Can't see them on this film. You saw them, didn't you, Ives?”

“Yeh. Oh, sure – went right under them. Chasing some people. No problem.”

“Sure you were.”

“Sure I wuz.”

Later Lou Ives got his marbles together and got smarter – but not much.

So much for First Combat Hops.

![Korea (photograph from a VC-61 [PP] photo pilot Ives was escorting over North Korea)](/sites/default/files/Burdett%20Ives30.jpg)

November 1951

CARRIER LANDINGS

A few incidents of Lou Ives’ landings on various crash factories:

The Wave-off on a cut: approaching the Bon Homme (CV-31) after a couple of exhausting deep armed reccos, I allowed the F9 to drift a bit to the right in the groove. Tommy Thompson (LSO) saw my problem and gave me a "Left Slant, Roger, Cut."

At the shorts, I hit stack wash. The machine would not respond to any attempt to regain the deck line. About this time I was eyeballing the troops in Vultures' Row.

I two-blocked the throttle, followed the induced right bank, and exited the pattern to the right of the island (and the vultures).

The procedure shook the troops, but the understanding mellowed the crew.

The cut on a wave-off: approaching the Bon Homme (CV-31) after a couple of exhausting deep armed reccos, I allowed the F9 to drift a bit to the right in the groove. Tommy Thompson (LSO) saw my problem was not salvageable and gave me a wave off.

At the shorts, I hit stack wash. The machine would not respond to any attempt to wave off to the right of the island. I cut throttle and booted left rudder. All hands dove to the scuppers.

I caught a late wire far right, drug to a stop with the F9's nose on the port deck side of the after 5'' mount and the starboard wing on the aft deck side. About a foot clearance on either side.

The pilot is always skipper (responsible) for his aircraft.

Statement of Burdett Louis Ives, Jr., LTjg 49629011315, USNR, concerning the loss of F9F-2B. Bureau Number 123671.

18 November 1951

At 0930, 13 November 1951, I took off [from the Bon Homme Richard (CV-31)] on an armed reconnaissance mission as number three plane in a three- plane flight. We were to recco the MSR from Wonsan to Yangdok. [Wonsan is on the mid-eastern coast, Yangdok due west in central Korea. The terrain is mountainous.]

The launch was uneventful, all three planes joining up and proceeding to Wonsan. The leader said he was going to keep 88% power to the beach, and I averaged about 88% all the way to Wonsan. We found the route and started weaving over it at about 2,000 feet above the terrain. We turned south and covered the adjacent route because our scheduled route had ground fog in the valleys. When we reached the end of the route we turned north. Number two man saw what he thought was a locomotive in a coaling yard. The leader and number two man reported small arms fire from a cluster of barracks-type buildings nearby. We made a run on the locomotive which turned out to be several boxcars and another run on the buildings.

As we continued north, number two man yelled, “Jink!” and I saw 37 millimeter bursts all around number one and number two as they dove. I then saw bursts about 50 feet off each wing-tip and ahead. I racked around and dove behind a ridge and left the puffs behind. A couple of miles further north we made a run on another marshalling yard. When I pulled out I had about 400 knots and pushed the throttle to 100%. The tail-pipe temperature went up to 800º C and the warning light came on (this is the first time I've had a temperature above 730ºC). I throttled back and the temperature returned to normal.

The leader and number two spotted more anti-aircraft to the left so we turned right. They both looked like the center of a powder donut as we pushed over. I turned down and left and saw tracers go up and burst where I would have been. This fire followed us for quite a ways and we had to go down behind the hill tops before it quit. About this time I heard what sounded like my blow-in doors bang four or five times. I thought nothing of it, as I had 100% power and was pulling “g's” every time I jinked. I joined up with the other two planes and used around 95% to stay with them (they later stated they were using between 88% and 90% at this time). 95% was not unusual because I was last man and would normally use more throttle to stay joined up.

We turned east and made a run on a marshalling yard with 10 boxcars in it. Shortly after we pulled out they started shooting again. 37 millimeter bursts followed us as we jinked. All of the flak appeared to be radar controlled as it burst at our level no matter what altitude we took, and very few bursts were more than 300 feet from us at any time. It burst both ahead and to the side. I saw bursts between the flight and myself, so I went south while they turned north. The anti-aircraft fire split, half of it following them and half following me. Every once in a while I would hear three or four loud thumps or bangs that sounded like the blow-in doors. I especially noticed it at this time because I was flying level at 85% at 5,000 feet (I assumed it to be a weak spring in one of the doors. It seemed to come from the left side, but I can't be sure).

We joined up heading east and made another run on a marshalling yard. The leader said that they were shooting at us, but I couldn't see any bursts. When we pulled out of the run, number two lost number one, but I had number two in sight so we proceeded toward Wonsan looking for number [one] who was also headed toward there. Number two and myself made a run on a warehouse and as I pulled up and leveled off at 80% at 5,000 feet. I heard the doors bang again three or four times. The leader told us to meet him over YoDo Island at 10,000 feet, so number two and myself headed toward the island and made a run on Wonsan, jettisoning the rest of our ordnance.

As we neared YoDo, number two saw number one and told him to head out toward the Force. Number two was about ¼ mile ahead of me at this time and told me that he would carry 94% until he was joined up with/h4Bon H/pomme Richar/h4d (CV-31) VF-781 the leader. I had to 18 November 1951use 98% to p class=/ptry to catch number two, but I believe that he widened the gap between us. I noted that my dive brakes were closed and I thought that he was cheating on his power. I was going to call him and tell him to throttle back, but at this time I saw him join on the leader and he throttled back. I caught them and throttled back to 85% to stay in formation (the leader and p class= /pnumber two state that they were using about 78% at this time). We passed over the screen at 10,000 feet at 72% and the leader called in for a landing. At this time I noticed a slight rhythmical acceleration and deceleration of the plane and the RPM was fluctuating about 1 to 2 percent on each side of 72%. I looked at the high pressure light and it was on, then it flicked off and went back on for about 5 seconds, then off again. I called the leader and advised him of my predicament. He called the ship and notified them. I also called them and told them to tell the LSO that I didn't want to take a wave-off.

I moved over to number two position and we pushed over for the ship as we got a “Charlie.” We broke upwind and made our landing pattern. I put my wheels down at 200 knots, flaps at 180 knots, raised my dive brakes, opened the canopy, and went over the check-off list. I had about 80% at this time. I slowed to about 120 knots at the 180º position and started my turn. I now had 115 knots, so I added a little throttle to hold this speed. The RPM gage showed 82%, but the speed stayed at 115 knots. I kept add and came over to the ing throttle as I flew p style=ast the 90º point, but the RPM stayed at 82%. At this time number one approached the “Cut” position. I called him and told him to take a wave-off. He answered, “I can't,” just as he took a cut and was out of the gear in plenty of time for me to get aboard. At this time I was ready to roll out into the groove when I noticed my RPM go from 80% to 70% to 60%. I figured I had had it. The throttle was two-blocked by now and I banked to the right to clear the stern of the ship, put the wheel handle in the “Up” position, picked out a wave, held a landing attitude at about 100 knots and chopped what power I had left just as I p class=hit with wings level about 3/4 of the way up the three-foot wave. I was about 20º to the right of the path of the ship. (I wondered if Tommy [Thompson – LSO] was giving me a come-on or a low at this time).

The landing shock wasn't bad – not much more deceleration than an arrested landing. The plane spun around 180º and (I noticed later) the nose section broke off. I sat in the cockpit for about three seconds and when I saw the plane was afloat, I unbuckled my safety belt, threw off the shoulder straps, stood up in the seat, contemplated the water and dove over the left side. I swam to clear the wing tip and then noticed I couldn't stay vertical in the water.

The air trapped in the legs of my rubber immersion suit [MK-2] raised my legs to the top of the water and I had to fight to keep them down. All this time I was getting dunked, and my movements were tiring me quickly. I figured that I had better get my life vest inflated first, but I couldn't find the toggles. After what seemed like 45 seconds and 10 or 12 dunkings, I finally saw them nearer the surface than I had expected. I had been groping for them around my waist area, but the jacket had a tendency to float to the surface away from my body.

After I had inflated my vest, and my immersion suit had taken in a couple of gallons of water through the neck opening, I gradually resumed a vertical attitude. It was at this time I saw the helicopter which had been hovering over me all the time. I knew I had to get out of the chute and I tried to unsnap my left leg strap. My hands were getting numb by this time [the water temperature was 55º] and I barely managed to get it unfastened.

The sling was moved over to me by this time and I grabbed it, but couldn't get it over my head because of the helmet and bulky clothes that I was wearing. Every time I tried to take the helmet off, I would submerge and I was getting so tired that I couldn't hold my breath for more than 3 to 5 seconds. I finally got the helmet off, grabbed the sling again and noticed that the helicopter aircrewman was about to come in after me. I tried to wave him back in and I guess he understood me. They yelled for me to get the chute off, but my hands were so numb by now that I couldn’t make my fingers work. I kept grabbing for the chest strap about 6 inches below where it was, and when I finally saw it up near my chin, I managed to get it unfastened. I was so tired by now that I couldn't slip out of the chute harness. The sling was drifting away, so I grabbed it, waved at the crewman who looked as if he was coming in again and finally got out of the harness.

I saw a “Can” nearby with crewmen lining the rails and I hoped that they would put over a boat before I made like a shot-put. Only my left leg strap remained, and I figured that it was now or never, so I grabbed it with my almost useless fingers and finally unsnapped it. The chute floated free and up to the surface of the water.

As much as I have looked at the chart, “How To Get Into a Helicopter Sling,” I forgot how to do it, so I did it by trial and error. By now I couldn't stay under the water for even three seconds without taking a breath, so I put the sling over my head. They started to raise it and I slipped out, I put it on the other way and they started reeling me in. I almost went to sleep in the sling, and when I got to the top I not only couldn’t help myself into the “copter,” I couldn't raise my foot to the outside step, so the pilot and crewman pulled me in bodily. They then shoved off for the ship.

After I sat in the helicopter for about 15 seconds I began to function OK and the aircrewman helped me out of my life jacket and survival vest. By the time we landed aboard ship I was responding OK, but felt pretty tired. I was met at the “copter” by my Skipper, the Flight Surgeon, the rest of my flight, and about 15 newsreel and TV cameramen.

My lacerated finger was treated, and I was taken below to sick bay, stripped of my gear, and put into the sack. They gave me a sleeping pill, but I felt like I didn't need it. Three hours later I got sleepy. That evening I got up, dressed, and checked out of sick bay.

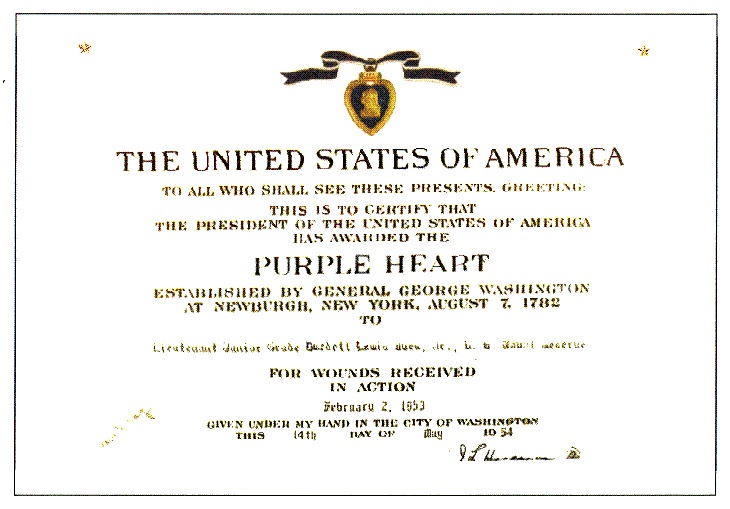

[Ives has no doubt that he was hit in the engine by 37mm fire on his first run – and the rest of his problems were caused by the faulty engine – he refused a Purple Heart for his minor injury.]

UNITED STATES PACIFIC FLEET

AIR FORCE

FIGHTER SQUADRON SEVEN EIGHT ONE

c/o FLEET POST OFFICE

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

23 November 1951

From: LTJG B. L. IVES, 496290, USNR

To: Survival Officer, CAG 102.

Subj: Survival Equipment, use of, and recommendations for.

Encl:

(1) Statement of ditching of F9F on 13 Nov 1951.

(2) Equipment carried on all flights

1. On 13 November 1951, during daylight hours, I ditched an F9F-2B jet fighter just aft of the USS Bon Homme Richard (CV-31) due to engine failure from North Korean flak damage. I was in the water about five minutes before being picked up by helicopter. All statements made in this report are based on this occurrence unless otherwise stated. I have made no other [previous] emergency ditchings, landings, or bailouts [a second combat ditching due to flak damage on 2 FEB 1953].

2. Arguments on leaving parachute harness buckled or unbuckled just prior to taking off or landing on a carrier.

a. Keep your chute buckled on at all times. I used to keep all of my chute straps bucked on tight during all takeoffs and landings because I felt that in the event of a water landing I would not be able to get the chute [and life raft] out of the plane before the plane sank. This argument was further augmented by the fact that the wing on the F9F is placed so far aft that it is impossible to stand on it and reach back into the cockpit for any item left there. This means that in order to recover anything left in the cockpit, the pilot would have to reach into the cockpit from either a position in the water which is just about impossible, or to stand on the steps in the side of the fuselage and reach back into the cockpit, but the time spent in locating these steps and the fact that one could very easily get his foot caught in one as the plane sank just about rules this procedure out also.

To sum, it up, I felt that the only positive and efficient way that I could retain my parachute (and more so, my life raft) was to leave the straps buckled at all times during flight, ditching, and evacuation of the aircraft, thus insuring that the chute would be with me after leaving the plane. This was before I ditched one.

b. Unbuckle your chute just prior to all carrier takeoffs and landings. When I ditched, everything went according to my planned schedule. I got into the water and away from the plane with my chute attached. Then the trouble began. I could not get the chute unstrapped. Some of the buckles (especially the chest strap buckle) were not where I expected them. My hands got so cold and numb that I had an extremely hard time unfastening the leg straps, and I was getting dunked under waves so often that I was rapidly loosing strength, and in order to undo the leg straps I had to get my head under water. By this time, I was getting so short of breath that this was an extremely difficult task. It is also possible the parachute to get hung up on some object in the cockpit, necessitating unbuckling the chute while the pilot is still in the cockpit, greatly endangering his life if the plane is sinking fast.

This leaves me two alternatives. One, to leave the leg straps unbuckled, and the chest strap buckled. This procedure would enable the pilot to leave the aircraft with the chute on, and not necessitate going through the rigorous task of unbuckling the leg straps. On the other hand, this may present a greater chance that the chute may get fouled on some protruding object in the cockpit, but if it does, the pilot only has to unbuckle the chest strap, which is relatively easy to do, turn around in the cockpit, unfoul the chute and throw it out. Or two: to leave all three straps unbuckled and as soon as the safety belt and shoulder straps are released, stand up, turn around in the cockpit, pick up the chute and raft and throw them over the side, following them out immediately. The chute and raft pack will float for sometimes as the one I was wearing bobbed to the surface after it had been submerged about four minutes while I was trying to get it off.

These last two procedures take a total of about 10 seconds to complete, even to the pilot being in the water. An F9F coming in for a landing with all of its ordnance gone and 80% of its 1000 gal gas tanks filled with air, will float for quite some time (at least 20 to 30 seconds – one even floated eight days until sunk by a destroyer) giving the pilot ample time to perform the above procedures. A fully loaded F9F (as on takeoff) will perform akin to a shot-putt, sinking completely below the water in something less than 15 seconds. In this latter case, the pilot would not want to be hampered at all by a chute.

As a result of my experience, I now take off and land over water with my leg straps unbuckled and my chest strap buckled, buckling the leg straps at an altitude of about I000' when clear of the destroyer screen. This procedure necessitates unfastening my safety belt in order to pull my chute leg straps snug, but it requires no effort and is easily done. The time and energy saved by not having to unsnap the leg straps after the pilot is in the water can very well be put to use inflating the raft and getting things squared away, or getting into the helicopter sling. Too much energy expended in the water prior to getting out of the chute may mean becoming fish food as it almost did for me.

3. Wearing the [Mk-2] immersion suit. Many pilots don't like to wear the rubber immersion suit because it is bulky, hot, and takes a lot of time and trouble to put on. I found that after several wearings, the suit becomes broken in and is relatively comfortable. If the suit is taken off immediately after each flight, the wearer will sweat very little, as I get hot and sweat most when I am in the ready room after the hop. (The F9F has a pressurized cockpit and a temperature control). My immersion suit did not have a zipper-slit for the “g” suit connection, so I had to wear the “g” suit on the outside of the suit. This procedure presented no difficulty nor was it uncomfortable. Some pilots do not wear a “g” suit with the immersion suit because they say water will enter the immersion suit through the “g” connection opening. This is true, but with any warning prior to ditching, the “g” suit connection tube can be placed inside the immersion suit and the waterproof zipper closed over the opening.

My feet had a tendency to float as the legs of my suit were filled with air. This trapped air is natural in the suit, and the legs will have a tendency to float until enough water gets into the legs of the suit to replace the air trapped there. This takes a couple of minutes. (The fact that I dove into the water head first, thus forcing the air in my suit toward my feet, and the fact that I was wearing my “g” suit over my immersion suit, thus making it hard for the air in the legs to escape, may have been partially responsible for the trapped air in the legs, but as I struggled to keep vertical in the water, I was upright most of the time, and my “g” suit did not fit tight enough to seal the air off in my legs). I think any immersion suit wearer will encounter the same difficulty. Nevertheless, it is a good idea to enter the water feet first when wearing the immersion suit.

It is impossible to keep water out of the suit. The design of the neck is such that a considerable amount of water will enter the suit through the neck. Very little water will enter the sleeves if they are drawn up tight, and I doubt if any will enter the waterproof zippers. This water very quickly heats to body temper-ature and aids in preventing the feet from rising to the surface. How this water in the suit would affect the wearer after many hours in the water, or if the wearer left the water for land, I cannot determine.

An immersion suit is an indispensable item of survival for pilot for any pilot, crewman or passenger that takes overwater flights when the water temperature is below 65°. In the five minutes that I was in the water, my body that was covered by the suit kept comfortable and warm while my hands, which were not covered by the suit, became cold, numb and almost useless in the same length of time. The drawbacks and inconveniences of the suit are so greatly overweighed by the necessity of the suit, that they are almost insignificant.

Many pilots say that they would remove the suit, or at least slit the legs after reaching land. This procedure is debatable, as the chance that one will have to take to the water again is very great.

4. Anti-“g” suit. I always wear my “g” suit because I make sharp recovery from and high “g” turns after leaving the target. The “g” suit enables me to stand about twice as many “g”s as I can without it, and is very helpful in reducing fatigue. It presented no difficulty whatsoever during my dunking.

5. Shoe-Pacs. The shoe-pacs are very essential if the wearer expects to avoid frozen feet if he ditches on land. I wear them every hop. In the water they were clumsy, as was all of my gear, but they did not inconvenience me as much as I had expected.

6. C-1 sustenance vest. I carry quite a bit of gear in my C-1 vest, on the theory that if I cannot use it, I can throw it away, or more so, barter it with the civilians or soldiers for obtaining their favor or some items of food or shelter from them. The vest did not bother me in the water at all, possibly because all of its weight was on my shoulders and it does not have cumbersome sleeves.

7. Gloves. If I had been wearing gloves, I doubt if my hands would have become so cold or numb, but the summer-type flying gloves are unsatisfactory in the water. When in the water, they become slimy and hard to handle.

8. Oxygen mask. All oxygen masks should be disconnected from the face before hitting the water. If the loose end of the mask connection tube drops under water while the mask is still attached to the face, one cannot help but inhale salt water. This has happened to several of our pilots.

9. Accessory connections. I did not disconnect any of my radio, oxygen supply tube (integral with the radio connections) or my “g” suit connection. I encountered no difficulty whatsoever in pulling them loose when I stood up. The radio and “g” suit connections slip out easily, and the oxygen supply tube should be connected to the shoulder straps, and will be discarded when the straps are thrown back.

10. Other gear. I encountered no difficulty at with any other gear that I was wearing.

11. Extra gear. I always carry a parka hood and a winter flight jacket in a separate package which I place on the console during flight. I do not wear this gear as it would become so waterlogged and cumbersome that my movements would be hampered and I would not be able to help myself in the water. I was taken below to sick bay, stripped of my gear, and put into the sack. They gave me a sleeping pill, but I felt like I didn't need it. Three hours later I got to sleep. That evening I got up, dressed, and checked out of sick bay.

COMMENTS

1. I am always going to completely unstrap my parachute prior to all landings and takeoffs. I had kept it strapped on because I felt that I couldn't get it out of the cockpit before the plane sank unless I had it strapped to me. Also the F9F wing is placed too far aft to stand on and pull anything out of the cockpit. I feel that the plane will stay afloat at least 15 seconds which is long enough for me to unbuckle my safety belt, stand up in the cockpit, throw the chute out with me hanging on and following it. The chute pack will float long enough for me to remove the life raft and inflate it.

2. Either the shoe-pacs or the immersion suit contained enough air when I first entered the water to raise my body to the horizontal position and duck my head under the water. (Very little water was removed from my shoe-pacs and about two gallons was removed from my immersion suit, so it was undoubtedly the suit that fouled me up.) As soon as I got enough water into the legs of the suit to force the air out, I righted and no more difficulty was encountered with the suit. The water in the suit quickly warms to body temperature, and is very comfortable. The value of the immersion suit is proven by the condition of my hands and fingers, which were not covered by it, and were so cold and numb that I could hardly move them; and the rest of my body (except my head) which was enclosed in the rubber suit had no ill effects whatsoever.

3. I will always look for the toggle or snap that I want to get at before I reach for it, as they are never where you expect them.

4. The fact that I wasn't wearing my oxygen mask probably kept me from inhaling a lot of water up through the supply tube.

5. The fact that the buffet helmet bothered me was probably due to my own personality and the fact that I wanted to be free of everything that bothered me. It has not bothered other swimmers in the past.

6. All the gear I was wearing was fairly clumsy and heavy, even in the water (especially shoe-pacs), but I figure that I can dress either for survival on land, or survival in the water and a compromise is hard to make. If I hadn't had to get rid of my chute, the going probably would have been easier.

7. I sustained no injuries except a cut finger.

8. I was wearing the following gear:

- Wool underwear and sox f. Life Jacket

- [Mk-2] Immersion Suit g. Buffet type helmet

- ½ length “g” suit h. Parachute with PK-2 type raft

- Shoe-pacs i. I was not wearing my oxygen

- Survival Vest (C-1) mask or gloves

- Life Jacket

- Buffet type helmet

- Parachute with PK-2 type raft

- I was not wearing my oxygen mask or gloves

9. The temperature of the water was 55° F.

COMMENTS ON ENGINE OPERATION

1. I did not use more than 80% or 85% after leaving the beach.

2. I did not notice any pump light prior to the time I noticed the High Pressure light on over the screen, but due to the light’s position it would be easy to not see it if it was on. I did notice that the High Pressure light was out when I was on the down-wind leg. The Low Pressure light never did come on and I would surely have noticed it if it had come on.

3. I never switched in emergency because I didn’t think the situation warranted it.

4. I believe that the flame-out would have occurred at any time that I advanced the throttle after I noticed the faulty operation of the engine.

Burdett Louis Ives, Jr.

1951

Item from U.S.S. Bon Homme Richard Cruise Book

Yesterday two of our prominent jet jockeys, LT Crandall and LT Ives, were on a recco hop far to the north. With their keen instincts of navigation and high degree of coordination, Crandall and Ives were exactly sure of their position. Therefore they did not hesitate to attack an estimated 4000 troops gathered near the square of a border town, the name of which is truly unpronounceable. With their rockets and 20mm guns they quickly broke up the gathering, killing at least 150. Then they leisurely shot up the general area before returning to the Bon Homme Richard far to the south. After going through the customary debriefing procedures, considerable doubt was expressed as to their exact position at the time of the attack. While a dozen or more charts were studied, Crandall and Ives suffered visions of third World Wars, international incidents, and general court martials [sic]. However, when the jury announced that they had been a good 100 yards from the Manchurian border, the boys heaved a simultaneous sigh of relief and Lt Crandall was heard to say, “Why, that wasn’t even close.”

Yesterday two of our prominent jet jockeys, LT Crandall and LT Ives, were on a recco hop far to the north. With their keen instincts of navigation and high degree of coordination, Crandall and Ives were exactly sure of their position. Therefore they did not hesitate to attack an estimated 4000 troops gathered near the square of a border town, the name of which is truly unpronounceable. With their rockets and 20mm guns they quickly broke up the gathering, killing at least 150. Then they leisurely shot up the general area before returning to the Bon Homme Richard far to the south. After going through the customary debriefing procedures, considerable doubt was expressed as to their exact position at the time of the attack. While a dozen or more charts were studied, Crandall and Ives suffered visions of third World Wars, international incidents, and general court martials [sic]. However, when the jury announced that they had been a good 100 yards from the Manchurian border, the boys heaved a simultaneous sigh of relief and Lt Crandall was heard to say, “Why, that wasn’t even close.”

So Much for Catshots

It appears that the standard signal when a pilot is ready for a catapult launch is the hand salute.

For the [1950-1953] VF-781 PACEMAKERS it was the finger salute.

The finger fired VF-781’s 3,900 Korean combat hops and uncounted training hops during our tours from first [1951], USS Bon Homme Richard (CV-31), and second [1952-1953], the USS Oriskany (CV-34) Korean tours in those three years from 1950 through 1953.

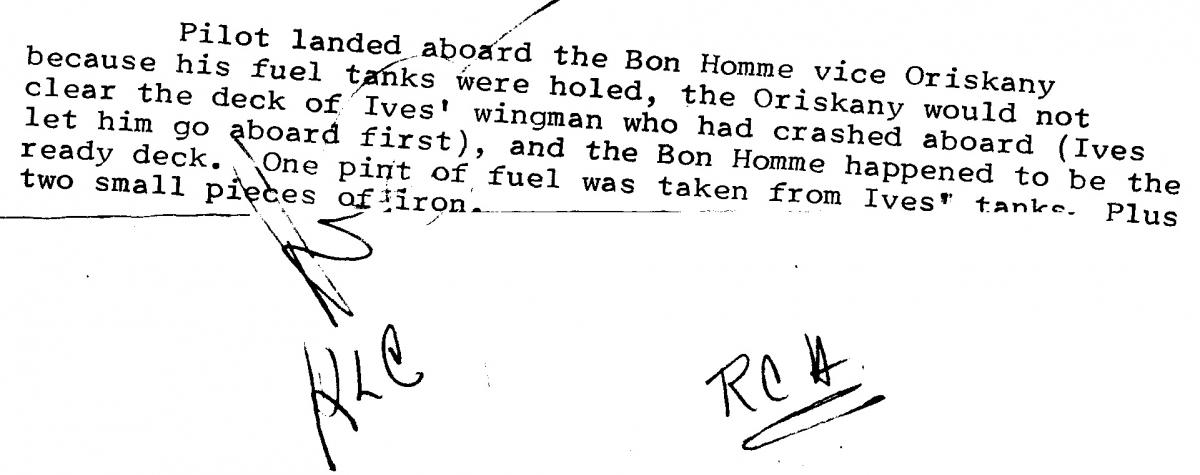

One memorable day on the Oriskany tour, a few imbedded arrowheads dictated that it was prudent for me to land aboard the Task Force ready deck – by chance the Bon Homme. ‘Twas like old home week reminiscing with the deck crew and ship’s company.

The following morning, patched and refueled with a minimum 1000 pounds – just enough to make the Oriskany and, without ordnance, about as light as the old F9 would ever get, I was trundled out and hooked to the port cat. Full bore, all set – and the cat officer got the finger.

LT R. L. (Bob) Giannini, USNR, forever permanent cat officer on the Bon Homme, was up to it – he had suffered through our antics on the prior cruise. I thought he was smilin’ from friendship and nostalgia, and realized too late that he had cranked in a full cat shot. Things began to clear abeam of the fo’rrd can.

I haven’t seen Bob Giannini since. If anyone bumps into him at a party, remind him that he was the perpetrator of one of the greatest coups ever pulled.

VF-781 Pacemakers became VF-121 Pacemakers during the Oriskany tour. I suspect the career Navy returned to the hand salute shortly thereafter.

In the history of the Navy, it must be recorded that the Pacemakers – for the years 1950-1953 – were the only squadron launched by the finger – the only squadron launched by giving the cat officer the bird in full view of the Captain, the Admiral, and the rest. Bless them all. Add throttle.

How’s the weather on the bridge, Jocko?1

1A comment ascribed to a WW II pilot on Joseph J. “Jocko” Clark’s boat about to be launched on a dawn patrol in cruddy weather. VADM Clark was CTF-77 at the time this anecdote was recorded, and was CTF-77 on the Oriskany during much of the VF-781 tour.

Section 4 – ON THE USS Oriskany (CV-34)

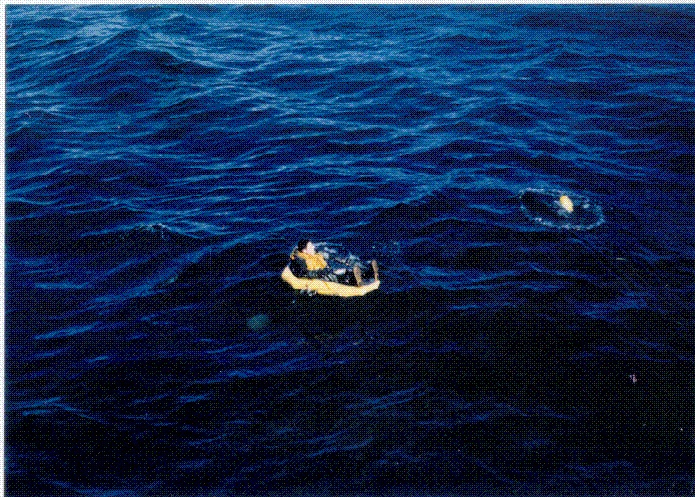

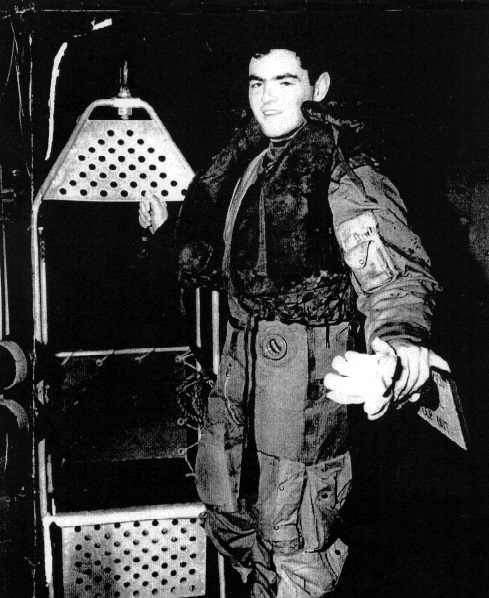

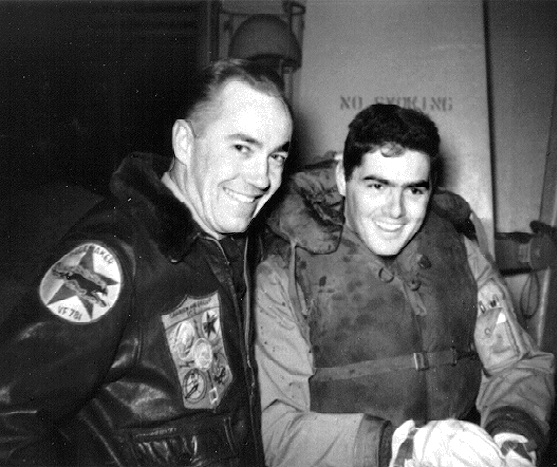

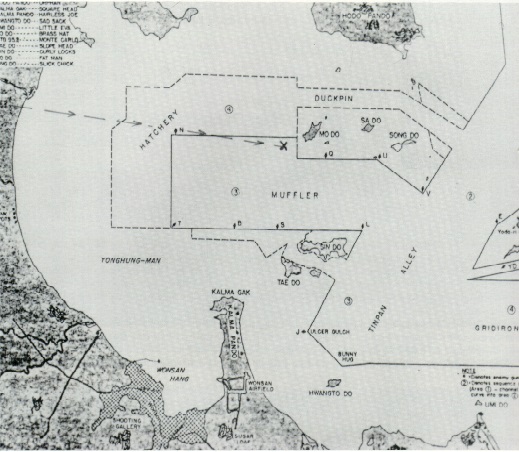

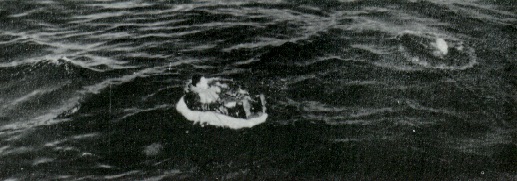

Groundhog Day 1953. Lou Ives (wearing MK4 poopy-suit) on a local tour of Wonsan Harbor, North Korea, after his F9F was properly bagged by the bad guys, resulting in a non-scheduled termination of flight. Picture from the deck of USS Hailey (DD-556). Air 27° / water 31° – background showing north shore with ice floes.

Groundhog Day 1953 Wonsan Harbor, North Korea

Statement of LTjg Burdett L. Ives, 496290/1315, USNR, of VF-781, 1315, concerning loss of F9F-5 aircraft BuNo 126152, Modex D-111, due to enemy anti-aircraft fire in the vicinity of Wonsan, North Korea, on 2 February 1953.

Weather and miscellaneous conditions:

(1) Weather: CAVU.

(2) Wind: west, 10 to 12 knots.

(3) Sea: 2 to 3 foot waves with some whitecaps.

(4) Water temperature: 33º F.

(5) Air temperature: approximately 25º F.

(6) I was in the water 13 minutes.

I was number three man in a flight of four F9F-5 aircraft to recco the main vehicular route from Wonsan to Hamhung. We briefed and were launched from the USS Oriskany (CVA-34) at 1145. Each plane carried 2xl00# G. P., 2x250# G. P., 2x260# fragmentation bombs and 800 rounds of 20 mm ammo.

We rendezvoused and proceeded to Wonsan Harbor at 10,000 feet, arriving over Wonsan at 1215. We immediately commenced bombing runs on some pre-briefed supply buildings at CU 5946, damaged one building with a direct hit, destroyed one smaller building, and left another large building on fire. I dropped all my external ordnance except one 260# frag in three runs. No anti-aircraft fire was seen or heard during these runs.

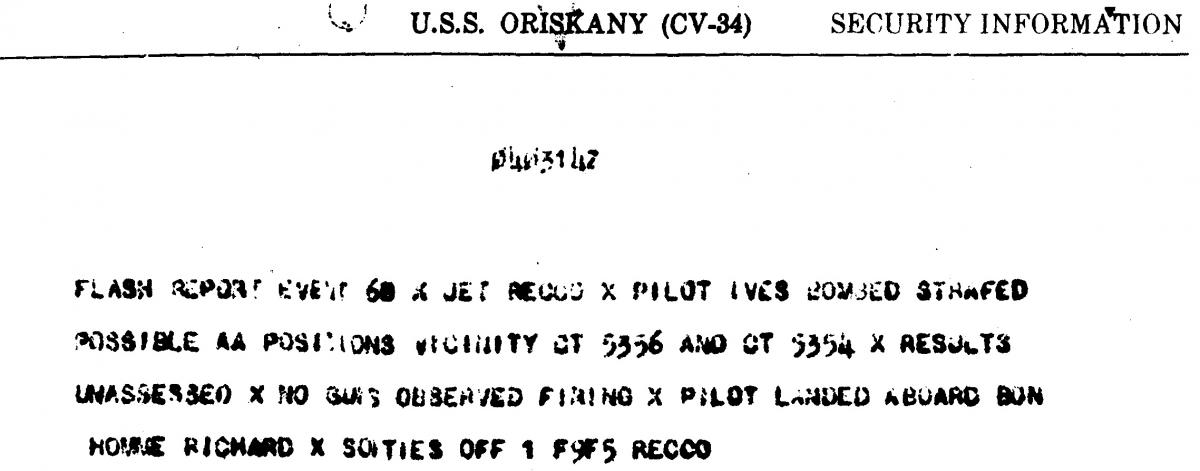

We then proceeded north along the route toward Hamhung. We split into two sections, my section following the leader about three miles. The leader spotted several ox-carts in the vicinity of CU 5449 and, with his wingman, made some runs on them. They had just completed a run when I saw a long string of ox-carts, stacked supplies, and people dressed in dark clothing on the road leading west from the above position into the hills behind the Wonsan valley. I was in a position to make a run on these targets so I called my wingman and made a strafing run from west to east, getting good hits all along the ox-cart train. As I pulled up I heard much irregular firing which sounded like small arms. I took evasive action and headed up the route after the first section.

My radio appeared to work normally, but all members of the flight seemed to have some communication difficulty, including several missed transmissions. The division leader had no receiver whatsoever until near the end of the flight [later comment: his phone jack was unplugged].

We then proceeded north looking for supplies hidden back in the ravines and foothills to the west of the main road. There was evidence of much activity both on the main route and the many secondary roads. I lost sight of the first section and climbed to 8,000 feet looking for them. I had searched for five minutes when the leader called and said that we would make one more run on the ox-carts we had spotted previously and rendp class=ezvous over Yodo/linbsp; Island CU 8142 at want to take a wave-off.t 12,000 feet and return to the ship. I rep c lass=turned to the ox-carts at 10,000 feet, calling the first section and advising them of the fire I had received from the area. Number two man rogered the information. As I started my dive, I saw a plane in its run below me, so I made a 360 degree orbit and preceded with my run.

I started strafing at 7000 feet, but saw that most of the traffic had dispersed by this time. I pulled out at 1500 feet and started to pull up with the intention of dropping my remaining bomb on the supply building that we had made our first runs on, as they were on the course to Yodo Island. At about 1600 feet, 450 knots, I felt and heard a loud explosion that seemed to come from below and aft. The plane acted much the same as an automobile traveling about 60 mph that has blown a left rear tire. It shuddered, slowed down and veered to the left, yawing moderately. This was the first indication I had that we were being fired upon by automatic weapons. I transmitted, "I'm hit, heading for Wonsan Bay." No one received my transmission – my radio was out.

I was about three miles from the shore, and had my doubts as to whether I could make it or not. The engine had lost all its power, none of the instruments were reading properly, the aileron control was very loose and sloppy, the emergency fuel system, high pressure pump, low pressure pump, and both fire warning lights were on. I pulled up until the plane seemed to want to stall. With no altimeter or air style=speed indicator, I could only estimate my altitude and airspeed as being between 3000 and 4000 feet at 150 knots just over the shoreline. The plane kept trying to roll to starboard and I discovered that I had no lateral control. I brought the right wing back up with the left rudder, pushed the nose over, and started a glide out over the water. I considered bailing out at this time, but I wasn't sure of my altitude, and was too close to the shoreline. (The altimeter read 9000 feet, the airspeed 75 knots). I brought the throttle back and closed the high- pressure cock, jettisoned my 260# frag, and tried to open the canopy with the hydraulic system. It didn't open, so I used the air bottle and it blew off ok. The cockpit filled with smoke and I could smell insulation or rubber burning.