“Autobiography”

“A Short Memoir of the Aviation Midshipman Program”

In 1945 if you wanted to fly for the Navy, forget it. The Navy had closed the door to pilot training long ago. Besides, they could pick and choose, and they only wanted the cream of the crop. But in April the Navy opened the door a crack and put out the word to the high schools in the Los Angeles area that they were recruiting for the Navy V5 college program. I could hardly believe it when my orders arrived assigning me to Occidental College. The orders read "qualified for actual control of aircraft."

In 1945 if you wanted to fly for the Navy, forget it. The Navy had closed the door to pilot training long ago. Besides, they could pick and choose, and they only wanted the cream of the crop. But in April the Navy opened the door a crack and put out the word to the high schools in the Los Angeles area that they were recruiting for the Navy V5 college program. I could hardly believe it when my orders arrived assigning me to Occidental College. The orders read "qualified for actual control of aircraft."

At Occidental and later at Cal Tech we wore sailor uniforms, marched to class, and learned about navy discipline and navy regs from a grizzled bosn's mate. I couldn't wait to fly. On weekend liberty, I paid for my own flying lessons.

The navy college program ended for us after two semesters on the USC Trojan campus. We reported for Selective Flight Training at NAS Los Alamitos, turned in our sailor suits, and were issued the green winter uniforms of naval aviation cadets.

If we thought it strange when the Navy taught us to fly before Preflight School, no one complained. Selective Flight Training in Stearmans [N2Ss] separated the sheep from the goats before too many tax dollars were spent on kids who couldn't learn the basic skills. After endless hours of close-order drill and KP, we advanced to the wash rack and finally to the flight line.

My instructor, a small, wiry, redheaded lieutenant named Battino, suspected I'd done some flying. When he wrung a confession out of me, I expected a reprimand, because buying your own flight time was strictly against the rules. The Navy didn't care to undo a bunch of wrong ideas put in our heads by ex-air force pilots turned into civilian flight instructors. Instead of a reprimand, Battino took me up over Los Angeles, where we spent a lot of time sightseeing. After five hours he declared me safe for solo. I said thanks, but elected to finish the syllabus and log the allotted flight time. Big mistake! The weather turned bad; Battino got reassigned; and the new guy, Lt. Patterson, started from scratch, graded me average, and piled on another eight hours in the air.

When time came for my solo we flew down to Miles Square an auxiliary field surrounded by orange groves and bordered by rows of eucalyptus trees. I climbed in the back seat and shot my three landings, proof to the Navy that at least I could fly a Stearman.

Just getting to Navy Preflight School was an adventure. I'd never traveled east of San Bernardino, nor had I been exposed to the hard, frozen winters of the Midwest.

It was a long, monotonous train ride from L.A. to Kansas City, with a connection to Ottumwa, Iowa. Maybe all the good rolling stock had been confiscated during the war, but this was February 1947 and the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific RR was the only connection between Kansas City and Ottumwa. They ran a donkey engine, a tender, and two rickety passenger cars with wood benches and a pot-bellied stove for heating. And that wasn't all. At midday we stopped at a small Iowa town, where the train waited while we hiked down the frozen main street to a boarding house and ate a meatloaf and potatoes lunch.

At preflight school aviation cadets were issued dress blue uniforms with brass buttons and gold anchors on the lapels. Within a short time we were given a choice: Sign up for two years as aviation midshipmen or return to civilian life. There would be no commission until the end of the two years. It was the beginning of a grand experiment to put future aviation officers on the same footing as Annapolis graduates. It was called the Holloway Plan.

There were some serious discussions in the barracks. The commanding officer was our last appeal. It was rumored he had run a battleship aground and would have midshipmen flogged for questioning authority. He turned out to be patient, but firm. "There are no other choices," he said.

We marched to class ahead of a drummer who beat the cadence. We learned about aircraft, engines, weather, and theory of flight. We could strip down a fifty-caliber machine gun and reassemble it blindfolded. No one questioned how this could be done in-flight while handling the controls of an airplane. We accepted that it was something one needed to know. We swam, boxed, wrestled, and on Saturdays practiced the manual of arms with M1 rifles while marine drill instructors barked orders. We studied navy customs, learned to copy Morse code, and survived two days in the woods on roots and bugs. OK. So we didn't really eat roots and bugs, we just learned which ones were edible. We actually ate K-Rations.

In the spring the Des Moines River overflowed its banks and flooded the town of Ottumwa. The Midshipman Regiment was called out of the barracks, issued rifles, and dropped off at strategic points to guard against looting. Midshipmen were praised in the local paper for taking rowboats into troubled waters and rescuing stranded flood victims. Many of us filled sandbags and plugging holes in the dikes. One local boy, looking for a job, asked how much we were getting paid. He disappeared when we told him forty-five cents an hour, the equivalent of $75 per month midshipman pay.

In the spring the Des Moines River overflowed its banks and flooded the town of Ottumwa. The Midshipman Regiment was called out of the barracks, issued rifles, and dropped off at strategic points to guard against looting. Midshipmen were praised in the local paper for taking rowboats into troubled waters and rescuing stranded flood victims. Many of us filled sandbags and plugging holes in the dikes. One local boy, looking for a job, asked how much we were getting paid. He disappeared when we told him forty-five cents an hour, the equivalent of $75 per month midshipman pay.

In July the Navy packed up its preflight school and moved us south to Pensacola for three more weeks of classes. After the graduation ceremony we returned to our rooms, stripped down to our skivvies in the oppressive heat, and waited for orders to Corpus Christi. I lay on my bunk, while my roommates broke out a deck of cards. Sitting around in skivvies, laying on bunks, and playing cards was an offense punishable by the piercing shriek of a marine lieutenant. My last hours of Navy Preflight School were spent marching around the grinder with an M1 rifle [an activity known as “Heel-and-Toe”].

At Corpus the Navy forgot we had ever soloed Stearmans. We learned to fly all over again in the SNJ. Flight gear issue was a special event. We lined up at ship's stores to receive a stack of clothing, a khaki flight suit, leather gloves, a summer flight jacket, goggles, and cloth helmet with radio earphones. The flight gear was ours to keep. We took it back to the barracks and smelled its newness, tried it on, and postured in front of the mirror. Possession of one's own flight gear was a rite of passage.

Rows of silver airplanes lined the tarmac at Cabaniss Field, awaiting khaki-clad student pilots wearing helmets and tinted goggles and carrying parachutes tucked under one arm. As we worked our way through stages of basic flight training with the SNJ, the khaki flight suits became stained with oil and sweat. Dirty flight suits hung in lockers. The ready room smelled like a gym. It was a contest to see who could go the longest without laundering his flight suit.

Instructor personalities ran the gamut from mild-mannered to profane. I lucked out with Ltjg. Voorhees. Maybe he was too soft-spoken. Instead of flogging me with a stream of profanities the day I landed long and rolled off the end of the runway at one of the practice fields, he merely said quietly (as we stood there waiting for a tow truck to pull us out of the mud), "Rogers, you should have added power and gone around."

Painstakingly we improved our skills, learning wingovers, chandelles, parachute eights, and other precision maneuvers. The Training Command had turned out a whole generation of pilots during World War II. The system had been tested and it worked. Instructors graded every flight. They were critical. They demanded perfection. They seldom invoked praise. They made notes in the air and scored each maneuver on a printed form. Satisfactory flights were graded in one of three groups, the bottom twenty, the middle sixty, or the top twenty percent. Unsatisfactory flights were stamped in large black, uppercase letters across the scoring sheet, heaping big worry on the student's shoulders.

Like stumbling around a haunted house in the dark, night flying offered a new thrill. Pity the instructor who sits in the rear seat on a dark night with no forward visibility, hoping the hamhanded kid up front doesn't get disoriented and pull up into stall on take-off.

A triple set of flare pots marked the active runway where a couple of instructors stood with a radio and flare pistol talking the students around a touch-and-go pattern. One moonless night while the instructors waited for planes in the high holding circle to exchange places with those in the landing pattern, a figure dressed in helmet, goggles, and parachute approached out of the darkness.

One of the instructors, wondering if this apparition might be some airhead who got lost in the dark looking for his assigned airplane, began a lengthy ass chewing. The second instructor, more perceptive than the first, recognized Midshipman Sam, who insisted he had landed short. When the crash crew found his SNJ, no one could argue the point. His plane was found short of the runway, short of the field boundary, outside the fence, and upside down. The crash crew also discovered where Sam, hanging in the shoulder straps, had dug a hole to extricate himself from the cockpit, then wriggled out and climbed the fence, still wearing his chute and harness. Whatever he lacked in depth perception that night, Sam made up for in determination, but he got no second chance.

One of the instructors, wondering if this apparition might be some airhead who got lost in the dark looking for his assigned airplane, began a lengthy ass chewing. The second instructor, more perceptive than the first, recognized Midshipman Sam, who insisted he had landed short. When the crash crew found his SNJ, no one could argue the point. His plane was found short of the runway, short of the field boundary, outside the fence, and upside down. The crash crew also discovered where Sam, hanging in the shoulder straps, had dug a hole to extricate himself from the cockpit, then wriggled out and climbed the fence, still wearing his chute and harness. Whatever he lacked in depth perception that night, Sam made up for in determination, but he got no second chance.

At Saufley Field near Pensacola, the Navy formed us into flights and lectured us on the fundamentals of tactics and formation flying. Join-ups were the initial step in learning to fly formation. The first few join-ups with the student flying and the instructor in the rear seat were a game of chicken for the instructor. The student was under the watchful eyes of an instructor in the lead. After a while though, you stop worrying about accidental stalls, but the imaginary alligators never go away. I could look down through the trees at sunlight reflected off the water and see glinting alligator eyes and rows of snapping alligator teeth. They seemed to be saying "Young boys. Fresh meat."

On a fateful day eleven midshipmen went aboard the USS Wright and sailed off into the Gulf of Mexico. Five more flew the planes out from Pensacola. The SNJ-5C came equipped with a tailhook, a jury-rigged affair that, in some planes, was lowered with a rope wrapped around the throttle quadrant. An improved device had knob attached to a cable inside an aluminum tube that lowered the hook. You pulled the knob out of a detent and let go. Freed of restraint the knob slid down a slot in the tube and the tail hook extended.

When the LSO swipes a paddle across his throat it means "the cut." And, oh yes, take your eyes off the LSO and level your wings. First landing, still in a turn I hooked a wire and stopped with the port wing hanging over the catwalk. after that it was easy, five more roger passes, with two wave-offs due to a fouled deck. That day, sixteen of us midshipmen qualified with a total of ninety-six carrier landings, no accidents, and only four wave-offs due to pilot technique.

After carrier qualification at Pensacola, midshipmen were offered the choice between single-engine and multi-engine advanced flight training. I chose the latter, believing that two engines or four engines would look good on a resume for a civilian flying job, if ever that became necessary. This was a decision I would regret. The orders came: Five midshipmen assigned to multi-engine training went back to Corpus Christi: Frank Rockwell and I got patrol bombers. Stan Pederson, Rick Cotton, and Don Day went into flying boats. Everyone else went to Jacksonville to fly fighters.

After carrier qualification at Pensacola, midshipmen were offered the choice between single-engine and multi-engine advanced flight training. I chose the latter, believing that two engines or four engines would look good on a resume for a civilian flying job, if ever that became necessary. This was a decision I would regret. The orders came: Five midshipmen assigned to multi-engine training went back to Corpus Christi: Frank Rockwell and I got patrol bombers. Stan Pederson, Rick Cotton, and Don Day went into flying boats. Everyone else went to Jacksonville to fly fighters.

The thought of heaving four-engine Privateers around the sky depressed me. We packed our helmet and goggles in mothballs and put on donut headsets and baseball caps. At this stage of training, barracks life had been left behind. Midshipmen lived in the Bachelor Officer's Quarters and joined the commissioned officers' mess. Evenings were often spent at the Officer's Club bar, where some midshipmen ran up huge liquor bills, which they later had to pay from their meager salary.

Rockwell and I paired off with an instructor to learn the rudiments of flying airplanes powered by multiple engines. After a few perfunctory lessons in a twin engine Beechcraft, the instructor handed us the controls with the usual words of caution and walked away.

Thereafter, Rocky and I practiced touch-and-go landings sweating profusely in the sultry climate of the Texas gulf coast. The sliding windows remained open for ventilation, and Rocky soon discovered that his covert hand reaching out the window and grabbing the wing leading edge, as I raced down the runway for takeoff, could spoil the lift and prevent the airplane from leaving the ground. Takeoffs soon became an unauthorized game of chicken. Would the co-pilot pull in his hand, before the pilot aborted the takeoff? When that game got boring, we climbed to a cooler altitude and practiced engine failures and other emergencies.

We left the SNB behind and began flying the PB4Y-2. Summer dragged on while Rocky and I sweated those ponderous brutes around the pattern, learning how to land with one, two, and sometimes three dead engines. A favorite instructor trick was to pull back the power on number two on the downwind leg. While the student ran through the engine-out checklist and began his turn onto base leg the instructor pulled number one, and the student suddenly found himself turning into two dead engines. Holding right rudder against the torque of numbers three and four was a feat not many of us could perform without the quadriceps of an Olympic weight lifter. Long over-water navigation training flights gave us a clue about what a midshipman's future would be like in a patrol squadron.

Fall came, the weather turned mild, and suddenly Rocky and I were finished. We woke up one morning to realize we had earned our gold wings. So had the group of seaplane pilots.

We purchased our wings at ships-service and spent the night before the ceremony giving them an antique finish with soot from a candle flame. The next day the five of us, wearing dress whites, lined up in the base commander's office while he pinned the Wings of Gold over our left breast and pronounced us naval aviators. Stan, Don, and Rocky all got orders to San Diego. Rick Cotton and I were ordered to Norfolk, VIrginia. The gold wings seemed to be a yard wide. In public they cast a hypnotic spell on young women, causing them to lose all inhibitions, or so we were told. But in truth we became a scattered brotherhood sent into the working world of the U.S. Navy to earn a paycheck, which came to $117 per month with flight pay.

At the Norfolk Naval Station officer's club, we were invited to be the guests of a group of British midshipmen aboard the heavy cruiser HMS Duke of York. A bos'n and sideboys piped us up the gangplank and onto the quarter deck with the honors due visiting officers. These guys were a wild bunch, having their own spaces on the ship, which were hung with no-parking signs and other relics acquired from unknown sources. In port aboard a British Navy ship liquor was an officer privilege.

"What would you chaps like to drink?" We were asked.

Someone said, "Hot-buttered rum," thinking it was the national drink of England.

“Sounds positively smashing, and by the way old boy, how do you make hot-buttered rum?" A puzzled silence followed. "Never mind. We'll improvise."

Bottles of rum appeared, a pound of butter and a sack of sugar were retrieved from the galley, and all of it was mixed in a pot of hot water. The results were predictable. We finally gathered-up our own in the wee hours of the morning, leaving a few English lads lying prone on the wardroom furniture, while we staggered back to our quarters, singing bawdy sea songs.

The officer behind the Atlantic Fleet assignments desk at Norfolk taunted me, as though a midshipman fresh out of the Training Command had a choice. ''Where would you like to go?" he asked.

"A utility squadron, sir," I answered, hoping for a back door entry into single-engine Corsairs or Bearcats, or even Turkeys

His eyes narrowed. He studied me as an entomologist might study a bug under a microscope. "I have an opening in a patrol squadron at Quonset Point, Rhode Island. P2Vs. Consider yourself lucky."

When I first arrived at Quonset Point, Patrol Squadron Seven was flying the P2V-2, the earliest production model, which carried a wide range of weaponry and was equipped with the latest antisubmarine warfare gadgetry, looking quite businesslike with six cannon ports in the nose and a twin 20mm turret in the tail. Out on the flight line I climbed through the airplane and sat in the cockpit and thought with a twinge of excitement that I might enjoy flying this machine. Except for the enormous vertical stabilizer, it seemed rather handsome with its shark nose and long, thin midwing that mounted a pair of nacelles housing Wright 18-cylinder, R3350 engines.

Assigned to a flight crew as "third pilot," a euphemism for navigator, I hoped for a quick transition to the right seat. The reality check came after spending a week at Fleet Airborne Electronics Training Unit. FAETU taught me how to operate the latest electronic wizardry and honed my skills as a navigator.

Cdr. George Bullard, skipper ofVP-7, swore me in as an ensign in the U.S. Navy one sultry evening in March 1949 at Guantanamo Bay, when the squadron was flying round the clock ASW patrols in support of Caribbean fleet maneuvers.

At ten in the evening the intercom crackled in the corner office of the hangar at Leeward Point Field, where I was serving my turn as the squadron duty officer and wondering if maybe the skipper had forgotten that my midshipman appointment expired at midnight.

"Mr. Rogers, report to my office." "Aye, aye, Cap'n."

I bounded up the stairs, slowing down when I reached the top landing to catch my breath, stood tall, walked into his office, and waited politely. He looked up from a cluttered desk, flashed a brief smile, and groped around for the papers. "Raise your right hand," he said. "Do you solemnly swear---"

I took the oath.

"Congratulations, Mr. Rogers." He shook my hand.

That was all. No drum roll. No pennants snapping smartly in the breeze. The skipper was a workaholic.

Shortly after the suicide of James Forrestal, the nation's first Defense Secretary, President Harry Truman appointed Louis Johnson as his replacement. Johnson squeezed the purse strings so tight that sometimes our planes were grounded for lack of fuel. His downsizing plan cut billions from the defense budget. A lot of young navy pilots were about to go out the door.

On Sunday, June 25,1950, I was called away from dinner in the Officer's Mess to answer a phone call from the squadron duty officer. "We're loading your plane with ordnance."

"What for?"

As we all remember it was the beginning of the war in Korea. Many former Aviation Midshipmen served there with honor, but a week later others of us were being separated from active naval service. I had spent a quarter of my life in the Navy. It didn't make any sense to me that we should be involuntarily shoved into civilian life while a hot war brewed in one hemisphere and a cold war hovered over the other, but top level decisions were seldom rational. I joined the Naval Air Reserve and flew on weekends, but my military flying career had basically ended.

I went to college on the Holloway Plan and spent a career as a civil engineer. Twenty years ago I took up flying again, and I'm still at it as a half owner in a 1969 Piper Arrow. As the saying goes, you can take the boy out of the country, but you can't take the country out of the boy.

“OH THE DUMB THINGS WE DID” *

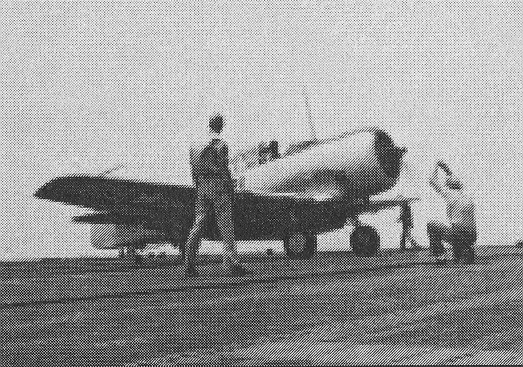

Following advance training in the PB4Y-2 and assignment to a Neptune [P2V] squadron at Quonset Point via Norfolk, I had logged most of my "yoke time" sitting on a stool with all that navigation stuff spread out in front of me. Six months had passed and I wanted some stick time. Our FASRON across the hangar had two airplanes, an SNJ and an F6F. Never having flown a single pilot airplane I made a bold request to the ops officer. "Can I fly your F6F" To my surprise he said '·sure". But he would need to give me a check ride in the SNJ.

A few days later' with the ops officer in the rear seat and me in the front seat of the SNJ, we were parked on the ramp behind a P2Y. A taxi signalman was motioning me forward and under the wingtip of the P2Y. It looked like my propeller arc would easily clear the wingtip and besides, the signalman must know what he was doing, so I released the brakes, rolled forward and ... no problem, plenty of prop clearance, ... but, in the next instant there was an audible crack as the low freq radio mast sticking up in front of the windshield struck the P2Y wingtip, broke off and fell across the canopy.

We shut down and surveyed the damage. "Didn't you hear me waving and yelling?" asked the ops officer directing his wrath at the signalman, but no doubt intending it for me. He stormed into the hangar and left me standing there thinking "well, that's the end of that". Pretty soon he came back with an F6F handbook, handed it to me (or maybe he threw it at me) and said, "Forget the check ride; read this. When you’re ready, I'll give you a blindfold cockpit check. After that you're on your own."

* The Aviation Midshipmen LOG, winter 2011.

“Flight Training PB4Y-2 and Turbulence”

Near the end of advanced flight training in PB4Y2s, a long over-water navigation training flight gave me a clue about what my Midshipman future would be like in a VP Squadron. We flew down to the Canal Zone from Corpus Christi--all night flight, lots of turbulence--we penetrated a cold front off Yucatan. Just before arrival at NAS Coco Solo, I stowed the nav gear and went aft to add a little extra weight in the tail for landing and to join our passenger, a naval officer ('blackshoe' type) enroute to CZ. The din of 4 hammering engines made conversation impossible, so I found a place to sit on the sand bags. These were carried for ballast to compensate for nose heaviness after a long flight had emptied the bomb bay fuel tanks.

As I sat there, I detected an odor wafting out of the darkened recesses. Could these bags be mildewed and rotting? Were they filled with fertilizer? Well, no! The odor, I learned later from an enraged plane captain, came from an errant "poop" bag, its contents flung about the after-station. Undoubtedly, during the night, the 'black shoe' passenger harkened to the call of nature and after utilizing the aluminum potty lined with a disposable paper bag--standard equipment in Navy patrol airplanes--he had attempted to dispose of same by opening the tunnel hatch and dropping the 'load.' Every crew member knew this was a no-no; air currents would hurl it right back at you. We don't know whether he ducked in time, but this much we do know: After landing he disappeared immediately, leaving the crew to clean up the mess.