“Getting that SIXTH Trap … A bit daunting at times”

On 4 May 1950, having completed FCLP training, Midshipmen Bob Aumack, George Carlton and Ed Crow, were together on the USS Cabot (CVL-28) at sea off Pensacola in the Gulf of Mexico ready to clear one last (big!) hurdle before earning those coveted Wings of Gold. We each needed six carrier landings in that magnificent 'Bent Wing' flying machine.

The carqual day at sea was planned pretty much like the FCLP sessions at Bronson Field. Most student pilots would be bussed to Cabot at pier-side Pensacola prior to it getting underway, usually around 0730, while the lucky few would fly out from Corry ready to enter the landing pattern as soon as Cabot (with Fox* flag flying) could setup into the wind. As the winds were usually coming on shore from south to southwest, carquals could commence without much delay, usually just a few miles off shore. As each pilot completed six arrested landings (there were no touch- and- goes on the old straight deck carriers) his U Bird would be chocked, engine running, in the launch position just forward of the barriers. Thus, the landing area was clear to bring aboard the next plane. With light loads and plenty of relative wind (built on cruiser hulls, the CVLs could easily make 30 kts), deck runs were standard procedure for the qualifying Corsairs. With two plane captains involved, one on either side, the "hot seating" routine prevailed - expediency over safety it would seem. Briefed to take enough time to ensure that all systems were "go," we, nonetheless, felt rushed along by the push and pull of flight deck ops aboard Cabot. With six hands in the cockpit assisting with cords, harnesses and belts, there was little time to settle in … as it were.

With Cabot steaming farther and farther from Pensacola, a sense of urgency seemed to prevail late in the day as all hands, ready to head home for some liberty and shore leave before the next carqual operations, focused on the last three planes in the pattern. Bob, observing from "vultures roost", had completed his six landings early in the day, while George and Ed were among the last three. George completed his sixth landing and was launched with orders to enter the "Dog" pattern, a holding pattern over the carrier for planes waiting further orders. Secure in the knowledge that for all intents and purposes he was now a Naval Aviator, George reduced power, leaned the fuel mixture and settled into a lazy orbit around Cabot. From 1500 feet he watched and waited for the other two to finish and then join him for the Victory Lap - a short hop back to Corry Field and a celebration at the "0" club.

Ed, on his fifth landing, hit slightly tail wheel first and blew the shock strut causing the tail wheel assembly to collapse. Clearing the landing area, he was signaled to shut the engine down. That Hog was through for the day. Ed, thinking, "I'm only one carrier landing away from my wings," was distraught to say the least. He stood on deck pondering the events of the day, wondering what might come next, as he watched the last Corsair catch a wire - a good three pointer and the pilot's sixth as it turned out.

The LSOs, consulting with the Air Boss and in all probability the CO as well, quickly decided to hold the last Corsair on deck, engine running, to give Ed a shot at his sixth landing. The consensus was that Ed's landing was not all that far from a good three pointer and since the Corsair had had tail wheel problems on carriers throughout its history. Ed faced "hot seating" one more time. With spirits soaring, he mounted the F4U-4. Feeling more rushed than ever, with the usual busy mix of six hands in the cockpit, Ed, mindful of the situation--last plane of the day, steaming away from Pensacola, only one landing to go, cross fire of terse radio and deck signals--ran through a quick check of the essentials and gave a tentative salute, signaling, "I'm ready to launch." The launch officer was already giving Ed a two finger turn up.

Climbing away from the ship, full power, gear and flaps down, Ed realized that he could not turn his head to the right, something was amiss. On reaching three hundred feet, he reduced power and started a left turn to enter the downwind leg, while determining that the cord from his lip mike was caught under his shoulder strap. Easing power to descend to one hundred feet for the downwind leg and continuing the turn, Ed fumbled to unplug the restraining cord. Just as the cord popped free, Cabot called for a fuel state. Unplugged, Ed could not respond. In those days we didn't call at the 180, so Ed, as a good student, had reasoned that he would not be talking to anyone, just listening. Cabot again called for a fuel state. But now, slowing in a descending turn, only a few hundred feet in the air, as Ed attempted to reattach his mike, the Corsair stalled. From its initial carrier trials in the early '40s the overriding concern of Corsair pilots was to avoid getting low and slow on a carrier approach. In a stalled condition, gear and flaps down, under 500 feet, it was virtually impossible to recover from a stall/spin condition in the Bent Wing bird. Ed applied full throttle, ailerons and rudder, as the Air Boss called, "level your wings, level your wings." It was too late. The U bird, fully stalled, under full power, torque rolled left, hitting the water nose down and almost inverted.

Knowing that Ed, his preflight roommate, was flying that bird, George watched anxiously from his perch some 1500 feet above the scene. "Plane in the water, plane in the water, port bow," came the Air Boss's urgent message over the landing circuit monitored by the the Destroyer escort. The Destroyer, lowering away a motor whaleboat, moved up quickly as Ed, his yellow May West clearly visible, popped to the surface. Compact, muscular and a good swimmer, Ed, using his Dilbert Dunker skills had cleared the inverted and sinking Corsair in record time. In a matter of minutes he was aboard the boat and enroute to Cabot.

A short time later Cabot reported that Ed was back on deck and apparently no worse for wear. Overhead, George drew a huge sigh of relief as he was ordered to proceed 020 degrees, 125 miles to Corry Field. Everything's coming up roses he thought, Ed's OK, and all I have to do is land this bird back at Corry, collect those Gold Wings and I'm off on thirty days leave--mission accomplished! About ten minutes later, Cabot was back on the horn telling George that his signal was Charlie - meaning return to the ship and land. Cabot followed with an explanation that student pilots could not fly solo flights over water--it was against training command regulations. Ripped from his reverie and with new visions of Ed's recent splash in mind, George reluctantly turned the Corsair around for another "Go" at Cabot. Following a long upwind leg, a wide downwind leg and an approach that was fast all the way, George took a "blue water" cut and landed without incident--his seventh carrier landing for the day. After all he was a Naval Aviator, almost.

Bob and George became Naval Aviators on the 8th of May 1950. Ed, after getting an "up" from a Student Pilot Disposition Board (Speedy Board), flew three warm-up FCLP flights and returned to Cabot with a band-aid on his forehead for his sixth landing on 12 May, receiving his Wings on the same day.

All career Naval Aviators, Bob went on to command the Blue Angels, while George and Ed commanded V A-21S and V A-66, respectively.

* “Fox Flag” flown at the flag hoist to signal ‘Flight Operations.”

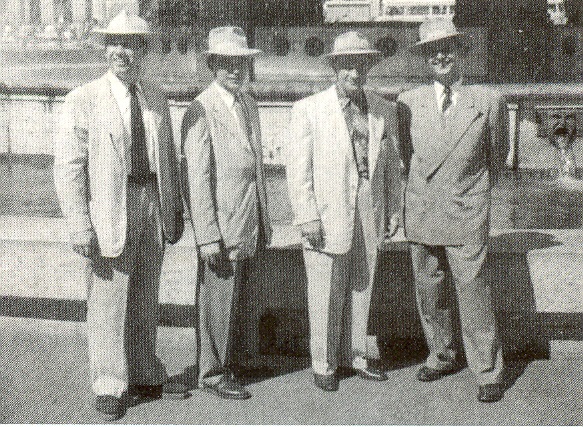

“Sixth Fleet Mufti”

In the early 1950s it was decreed by ComSixthFleet that officers on shore leave should blend well with the civilian populous so as not to be conspicuous. Thus, all officers were required to wear jackets, ties and hats while ashore. The hat of choice was the Italian Borsillino, a soft felt fedora that could be rolled and stored without fear of wrinkles or creases. In the photo from the 1952 Med deployment of USS Wasp (CV-18) are, left to right, LTJG George "the bear" Carlton; LTJG Charles "the tool" MacDowell; LT George "yotz" Muirhead, all from VA-15; and LT Herman "hormone" Grubbs, an LSO from the CVG-l staff.

In the early 1950s it was decreed by ComSixthFleet that officers on shore leave should blend well with the civilian populous so as not to be conspicuous. Thus, all officers were required to wear jackets, ties and hats while ashore. The hat of choice was the Italian Borsillino, a soft felt fedora that could be rolled and stored without fear of wrinkles or creases. In the photo from the 1952 Med deployment of USS Wasp (CV-18) are, left to right, LTJG George "the bear" Carlton; LTJG Charles "the tool" MacDowell; LT George "yotz" Muirhead, all from VA-15; and LT Herman "hormone" Grubbs, an LSO from the CVG-l staff.

Could anyone doubt that this foursome blended well with the locals? The location is in doubt, either Palmermo or Taranto? Perhaps a sharp eyed reader could help with the ID?

CAPT George Carlton, USN (Ret.)

“Barnowls and Brakes”

In the spring of 1966 I was XO of the VA-215 Barnowls and led a flight of four Skyraiders on a pre-briefed mission into Laos. We were each loaded with full 20mm ammo, four 500 pound bombs, 300 gallons of fuel in the centerline drop tank and full internal fuel (360 gallons). This was a relatively light load for the A-I, allowing us six to eight hours of mission time. We launched from USS Hancock (CVA-19) on Yankee Station 125 miles east of the DMZ at 1000 and proceeded to a coast-in point just south of the DMZ.

Arriving a few miles north of Chepone, Laos at 1130, we received a hot reception from a 37mm, AAA battery. We were at 6,500 feet and as I ordered the flight to break hard right, the fire fell short and below us. I cursed myself for not giving Chepone a wider birth. By our Rules of Engagement (ROE), we were forbidden from engaging in duels with AAA batteries not directly involved with our assigned mission. This was an example of a rule that I fully supported in that the risk/reward ratio was not favorable. What was worth the risk?

Our target, assigned by seniors in the chain-of-command, was a river ford (a place where a body of water can be crossed by wading!) along the Ho Chi Minh trail about 85 miles northwest of Chepone. We arrived in the target area shortly after noon and easily found the river--actually a stream--no more than 50 feet across. From 6,500 feet, I couldn't make out the ford, so I detached and dove down for a look, alerting my wingmen to suppress any ground fire that I might stir up.

After a couple of passes up and down the stream I found the ford, which looked to be some rocks piled up just below the water's surface and perhaps eight to 10 feet wide. I gave the flight a mark-on-top and told it to start the drops, as I climbed back up for my run. Dropping strings of four each, diagonally across the ford, we took out the entire ford including both approaches. As I looked over my shoulder on the climb out, judged the VC now had a nice swimming hole. It would probably take only eight hours to construct a new ford. The lack of hostile fire was an indication of how that crossing was prized.

Setting a course for Chepone, we settled back into a loose deuce formation, a holdover from WWII Naval Aviator Jimmy Thach's tactics, which gave good 360 degree surveillance around the flight. Remembering the reception we received passing Chepone earlier, I considered putting a few rounds of 20mm into that pesky AAA sight, but discipline prevailed and we turned well north to avoid any temptation.

I couldn't help thinking how the ROE were hamstringing our TACAIR efforts in stopping the flow of material down the trail from north to south. Here we were hitting a stream ford, while vast concentrations of SAMs, ammo and fuel sat fully exposed on the docks at Haiphong--protected by a 10 mile circle into which we could not fly, under the ROE. Theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do or die. Tennyson's words came to mind.

Under the strategy of the day, we were not allowed to interdict until the SAMs were in place and active; until the ammo and fuel had been reduced to small packets and loaded onto trucks, wagons, carts, bicycles; until all was beyond 10 miles, moving south under cover of darkness and dense jungle canopies. The absurdity of the situation seemed obvious, but as a squadron XO I assiduously avoided revealing my personal views in the presence of the junior pilots. Taking each mission as it came, I put the best possible face on any discussion of raison d' etre--should it come up.

"Spads flying west of Quang Tri, do you hear me? This is Skylark, over."

The transmission coming in over the guard channel broke my reverie like a thunder clap.

"Skylark, this is Barnowl one, I'm in that vicinty," I responded. We established communications on another channel. Skylark was a USAF Forward Air controller (FAC) flying an O-1 Birddog a few miles south of us. A flight of F-I00s had just left him, low on fuel after a couple of passes. Skylark had a concentration of VC pinned down in earthwork trenches and bunkers. I wished we still had the 16 x 500 pounders we had wasted on the ford. All we had left were our 20mm s--some 3,200 rounds. Maybe we could be helpful.

Setting up a racetrack pattern and spread out to keep continuous fire on the target, we started our runs using 35 degree dive angles. After my first pass, Skylark urged us to get steeper, advising that the trenches were narrow and very deep. We tried 60 degree runs really steep for strafing. Still not effective, he radioed.

I said, "OK Barnowls, lets take it upstairs and use the brakes." In 16 years of flying Skyraiders, I had never tried strafing from a 70 degree dive, but the Skyraider was equipped with huge dive brakes designed to allow high angle dives while holding down speed and thereby providing more time in the run with increased accuracy resulting from lower release and pull out altitudes. We set up to roll in above 10,000 feet, thus allowing ample time to establish a steady run at or above a 70 degree angle. Coming in at that angle to the target, the attitude of the plane is between 90 and 110 degrees--pointed virtually straight down!

The FAC was ecstatic: "Pour it on, Barnowls!" he urged. We made three or four 70 degree runs each, expending all our ammo--demonstrating once again the versatility and staying power of the magnificent Skyraider. As we collected ourselves, Skylark gave us a Bomb Damage Assessment (BDA) of 25-30 Killed In Action (KIA), which we duly reported in our debriefing back aboard Hancock. In hindsight, the war had turned into a numbers game as we reported sorties flown, ammo expended, target hit, enemy killed etc.--all feeding DOD's penchant for data to sustain its insatiable demand for operations analysis. One wonders what measure of effectiveness it found in our ford mission. Even then I puzzled over the KIA numbers the FAC reported, wondering how he make those determinations from the air? Were the numbers doubled somewhere up the line, having been reported once by the USAF and once by the USN? Who knew? Who cared? Back on Hancock there was little time to reflect as we were already hard at work on the next mission. We were confident that the chain (all the way to the Commander-in-Chief) knew what was best. After all John F. Kennedy had said: "We shall pay any price … oppose any foe to assure … the success of liberty."

We were paying and opposing; it was our duty, but the docks at Haiphong remained off limits.

“That is Your Target, Attack!” *

One night in the spring of 1966, tasked with a road recce south of Vinh, North Vietnam, we were kept mostly “feet wet” as the weather on shore was well below minimums with low ceilings and squalls. A flight of four AD-6s from the VA-215 Barnowls, we were loaded with full 20mm ammo, magnesium parachute flares, 19-shot packs of 2.75 inch rockets, 250 and 500 pound bombs. After several unsuccessful attempts to reach our assigned road segment, the bad weather prevailed and as flight leader, I decided to proceed to Danang for a radar controlled drop. Over the Gulf of Tonkin the weather was better with ceilings rising to above seven thousand feet to the east.

One night in the spring of 1966, tasked with a road recce south of Vinh, North Vietnam, we were kept mostly “feet wet” as the weather on shore was well below minimums with low ceilings and squalls. A flight of four AD-6s from the VA-215 Barnowls, we were loaded with full 20mm ammo, magnesium parachute flares, 19-shot packs of 2.75 inch rockets, 250 and 500 pound bombs. After several unsuccessful attempts to reach our assigned road segment, the bad weather prevailed and as flight leader, I decided to proceed to Danang for a radar controlled drop. Over the Gulf of Tonkin the weather was better with ceilings rising to above seven thousand feet to the east.

Faced with persistent ordnance shortages during the spring of 1966, we had several options for disposing of unexpected ordnance, after every effort to put it on assigned or secondary targets had been expended. We routinely landed back aboard with 20mm ammo and rockets, but bombs were another matter. The radar controlled drop programs at Danang was a good choice, but not always an option due to time and fuel constraints. After checking in with the controller at Danang and establishing positive radar contact, the controller would vector the flight (usually north toward the DMZ), assigning heading, airspeed and altitude. Having advised the controller of the load to be expended (typically four to five bombs per aircraft--250 to 1000 pounders), the internal system (a mystery to us) chose the target and completed the dynamics of the drop. We could drop all at once or trail the releases on interval. The controller called the shots and we dropped on command, usually from around 12,000 feet, usually in foul weather and often at night. Not seeing the targets was a frustration, compounded by never receiving any bomb damage assessment (BDA)—al in all something of a hush-hush program.

Tiger Island was another choice. It was a small uninhabited island located just offshore from the DMZ. Being a designated disposal target, it probably ranks as one of the most bombed spots on earth. I use "uninhabited" advisedly as pilot reports of hostile fire from the island persisted throughout my tours there in '65, '66 and '67. Of course, as a last resort bombs could be dropped at sea--not very satisfying.

A few minutes after advising home base [USS Hancock (CVA-19)] we were feet wet, 100 miles west en route to Danang to expend ordnance, we were shifted to another CVA-19 frequency. After establishing radio contact and positive radar control, we were given a vector with orders to proceed at best possible speed to a line of bearing north of Hancock where enemy PT boats were proceeding south at high speed. I ordered the flight to crank on normal rated power (2,600 rpm and 46 inches of manifold pressure)--the maximum continuous power setting for the Wright R-3350 engine. With the drag from our weapons load holding us back, we flew at 6,000 feet and 210 knots. I considered getting rid of the bombs but rejected the idea, thinking that we might need them.

The controller estimated the "skunks" were 80 to 100 miles north of Hancock. I advised the flight to be ready to use guns and rockets on the first pass, thinking we'll stop them and then use the bombs to finish the job. Knowing that Hancock couldn't be radar tracking anything on the surface at that distance, I asked how they were being tracked. The controller responded that they were tracking with “Echo Charlie Mike” [electronic countermeasures (ECM)] We were about eighty miles north of Hancock at this time and as I was pondering the situation, a slight doubt began to creep in. Having been ECM Officer in Essex for two years and CIC Officer for CTF-77 the prior year, I knew that ECM tracking and identification was marginal at best. About that time, Paul Charvet (Paul was lost the following year flying from Bob Homme Richard in the Tonkin Gulf), called, “White light, twelve o’clock down.”

Sure enough, there it was, a dim, vertical, pencil-thin, beam of light shining up from the blackness below.

“I’ve got it,” I said, starting a right turn so we could enter our runs with left-hand roll-ins. Hancock, hearing our chatter, radioed, “Barn Owl leader, that is your target. Attack!”

The order was unequivocal. Yet my doubts prevailed. I quickly assessed the situation and thought, "What the hell is he showing that light for? We've got him, even if he kills the light. We'll get him under the flares."

In rapid order I passed the lead to my section, Jerry Collins and Tex Button, directed Paul to tail in behind Tex, and called for a racetrack pattern around the light to await my call to attack.

"I'm going down to have a look," I advised the formation. I reset the ordnance panel to drop flares and spiraled down to set up a run from north to south at 3,000 feet. Popping one short, one on top and one long, I flipped the plane around quickly to avoid losing the target should he decide on a hard turn. The flares worked as advertised, providing near mid-day brightness.

And what to my wondering eyes did appear but USS Sacramento (AOE-1)! Under the flares I could read her hull letters loud and clear as I passed down her port side from bow to stem at deck level.

Some 33 years later, I have a vivid memory of that huge gray hull steaming along under the flares, completely unaware of what might have been. She was loaded to the gills with fuel and ammo. Hancock's response to my report of a friendly contact was simply, "Roger, out." Our drop on Tiger Island and return to the ship was uneventful.

After debriefing with the squadron air intelligence officer, Dick Foland, I hung around the ready room for another hour, now well past midnight, thinking that surely Hancock's CO would want to have a chat about the near demise of Sacramento, one of our very own ships. There was no doubt in my mind that he had been in CIC calling the shots. Fred Nelson, our squadron skipper, and I discussed the situation and decided that the Old Man, having had a pretty rough day, had probably hit the sack and would want to talk it over in the morning. I then gratefully downed the shot of medicinal brandy supplied by the air wing's thoughtful flight surgeon, and turned in. No discussion with the ship's CO ever materialized.

Later I talked with CIC officers. Turns out Hancock and its accompanying DDs had been tracking the surface search radar (SPS-1O) on Sacramento which had fingerprints (frequency, repetition rate and pulse width) nearly identical to Russian gear installed on the North Vietnamese torpedo boats. Thankfully, I had experienced similar erroneous evaluations in my CIC days. This sort of error usually occurs when ECM operators first check against enemy lists of parameters and fail, in their excitement, to check friendly lists as well. I also suspect there may have been some Signal Intelligence involved.![Wings of Gold spring 2000 Carlton was XO of VA-15 during this story, CO the following year. Above is an AD [NM304] on a RESCAP over the Gulf of Tonkin](/sites/default/files/George%20Carlton4.jpg)

Until now, I've been content to let the matter rest, but considering enough time has passed to assuage any lingering embarrassment and the story needed telling--with a view towards illustrating there are times when subordinates must act on their own initiative, especially when the stakes are high. Naval Aviation has a rich tradition of fostering a resolute disposition toward initiating appropriate action when confronted with complex and changing conditions. As I read current journals (Hook, Proceedings, Wings of Gold, etc.) and talk from time to time with younger active duty types, I'm left with the impression some of the willingness to act decisively in situations lacking complete definition has been discouraged by a climate in which rigid adherence to doctrine (coupled with passive acceptance of changes adverse to unit cohesion, morale and readiness) prevails at the cost of initiative.

Our Naval heritage is rich with examples, of heroic leadership under stress: “I have not yet begun to fight;” “Don't give up the ship;” “Damn the torpedoes;” “Take her down;” “Turn on the lights;” “Senator, there is not enough thrust in all of Christendom to make a fighter out of the F-111;” to cite a few. Unless subordinates see examples of fearless initiative in their leaders, they in turn are unlikely to act in the best traditions of the Naval Service when the chips are down.

I am also left with the impression that promotions today are based more on subordinate conformance than on demonstrated leadership. The final questions must always be: Will this make us better warriors? Does this improve our readiness to fight?

If the answer is no, then leadership must prevail to right an obvious wrong. Failing to act, the easy way out will often inflict one more chink in the armor of a Navy already over-tasked, under-equipped and undermanned.

* George Carlton, Tale Winds, Wings of Gold, spring 2000; © 2000.

“Essex, Tom Moorer and Me” *

In 1959 I was ECM and CIC officer aboard USS Essex (CVA-9). Two weeks before deploying to the Mediterranean I attended a meeting (classified secret) with CDR Bill Sisley, Ops Officer and engineers from BuShips. Essex was to install a prototype countermeasures system on the mast along with a control box in the ECM room.

In 1959 I was ECM and CIC officer aboard USS Essex (CVA-9). Two weeks before deploying to the Mediterranean I attended a meeting (classified secret) with CDR Bill Sisley, Ops Officer and engineers from BuShips. Essex was to install a prototype countermeasures system on the mast along with a control box in the ECM room.

Cold War threats of the day to our forward deployed carriers included Soviet Bison and Bear bombers equipped with air-to-surface missiles. The ECM device, rapidly installed just days prior to departure, was a last ditch defense system designed to thwart missiles during the last few seconds as they locked on with terminal radar guidance. As it had no official designation, I dubbed our prototype device the "Zapper." There was no instruction manual, but the BuShips team did leave a 1st Class Petty Officer with us for maintenance and testing. I assigned my best ECM PO to work with him.

On 7 August Essex got underway for the 6th Fleet as a unit of CARDIVSIX under the leadership of RADM Tom Moorer. Moorer, destined to become a four-star admiral and a legendary figure in Naval Aviation, and his staff would transfer to Saratoga after the Atlantic transit. The Zapper was on the mast, the ECM room had an on/off switch, a red warning light, a push button to activate the jammer and that was it. CDR Sisley told me, "You figure it out, it's all yours." VF-13 was aboard with their F4Ds, the bat wing fighters called "Fords." Only three of us, the BuShips PO, my PO and me were fully informed about Zapper's existence and purpose.

Enroute, I determined the F4D's Airborne Intercept (AI) radar had frequency and pulse repetition rates similar to the terminal guidance system on the soviet missiles. As we passed the Azores the Fords were scheduled for night intercept hops. On impulse I decided to run some tests. Not wanting to make a big deal of it, I approached two junior Ford pilots and asked them to make runs on Essex prior to landing. I would be their air controller, working from a control station just outside the ECM room so that I could easily coordinate with my POs. I told the pilots we were familiarizing my ECM crew with their radar signals and that I might, as a test, send out a counter signal or two while they were locked on.

The Fords made two runs each coming in at 500 feet from 20 miles out at about 400 knots. They locked on at 15 miles and each time my POs reported a red light and hit the jammer button in response.

Not wanting to raise concerns, I broke the runs off at five miles to avoid overflying Essex. It went like clockwork. In a debrief in the back of VF-13's ready room near midnight, the pilots reported interference on their radar screens at about 10 miles out. Satisfied Zapper worked, I turned in for the night.

At 0900 next morning, it hit the fan. The CARDIV ops officer, CAPT Roy !saman (later RADM and my former squadron CO whom I greatly respected), summoned me to flag plot. A CDR who was staff CIC asked for my version of the event and said reports had been received that I had-conducted unauthorized ECM tests involving jamming the Ford's radars. I explained everything, stressing I ran the tests prior to Gibraltar. The CIC officer was out of sorts. He said an Italian cruise ship had passed some 40 miles north of us during the tests. He concluded I could have compromised the existence of Zapper.

This bordered on the absurd, and I assured him Zapper was directional and that the runs were clear of all surface contacts. Except for the cruise ship there were no other surface contacts during the exercise.

Roy and the CICO went out on the flag bridge and talked with RADM Moorer out of earshot. Roy and Moorer appeared calm, but the CICO was animated. Ten minutes later I was told to report to the admiral, who was sitting in his chair. I came to nervous attention for what seemed an eternity. Moorer just looked me over. Finally, he said, "Please stand at ease and tell me your version of this.” I related the whole story, stressing the Zapper needed testing, that the tests were successful and in my view there was no risk of compromise.

After a pause he said, "I could put you in hack (confined to one's room with nothing to read but Navy Regs) for a few days, but I won't. In the future keep your seniors informed. It might not be as efficient, but it will keep you out of hot water." He shook my hand and said, "I admire your initiative, now get back to work."

I left flag country greatly relieved, a bit wis for two years and CIC Officer for CTF-77 the prior year, I knew that ECM tracking and identification was marginal at best. About that time, Paul Charvet (Paul was lost the following year flying from er, and walking a bit taller.

* George Carlton, Wings of Gold, Summer 2005; © 2005.

“Tule Fog”

On my first trip to NAS Lemoore, California in November 1965, driving our trusty 1961 VW Bug north into the San Joaquin Valley, I was introduced to Tule fog. My family stayed behind in San Diego while I looked forward to A-1 Skyraider training in the RAG, VA122. I'd visit them on weekends. On passing Bakersfield, ceiling and visibility dropped to something just above zero/zero. This condition persisted for the next 100 miles to Lemoore. I asked about the fog next day at the squadron.

"Get used to it," was the standard response, "it will be with us for the next several months."

"Get used to it," was the standard response, "it will be with us for the next several months."

I soon learned that the locals approached driving in the fog by maintaining speed. They reasoned that everyone should drive at the speed limit, and that collisions would be avoided if no one slowed or stopped. I flew wing on 18-wheelers, allowing the big guys to run interference, as it were.

During the next few months I got close up and personal with Tule Fog, both flying and commuting. Almost a daily occurrence, the fog set in just after sundown and began to lift around 10 a.m. next day. It blanketed the valley from the deck to around 1,000 feet. Some remember it reaching to several thousand feet.

Tule is a native word meaning bulrush or cattail. These rushes were abundant along riverbanks and low lying marshes throughout the San Joaquin Valley--areas ripe for ground fog. Farming and irrigation began in the fertile valley in the 19th century and fog expanded along with the increased moisture.

I have always wondered why the Navy chose to build its primary west coast training field in such a location. Indeed, in the winter of 1966 we did most of our flying from fog-free regions in EI Centro in California and Yuma in Arizona.

In April, following carquals on Midway and completion of the RAG I joined the VA-215 Barnowls as XO and deployed to Yankee Station. A few months later we returned to our home base at NAS Alameda and were scheduled to deploy in Bon Homme Richard the following January. The Barnowls had an intense training schedule, including weapons training at Fallon, Nevada, day and night carquals on Bonny Dick long low levels—Sandblowers--which entailed magnum fuel loads that allowed us to stay up "forever" in our wonderful and rugged A-Is.

In December Jack Monger, CAG-21, summoned COs to a meeting at 1000 in Lemoore. VFs 211 and 24 were at Miramar while VAs 212 and 76 were at Lemoore. Since I was to relieve Fred Nelson as CO of the Barnowls in January, it was decided I should attend the meeting.

I flew VFR on top with plenty of fuel on board--enough to complete a round trip to Denver, Colorado and back. Passing Fresno, expecting the Tule fog to lift enough for me to land by 0930, Lemoore tower reported the field closed with zero/zero conditions. I was cleared to hold over the field at 5,000 feet.

When asked how long I could stay on station and what was my alternate destination, I jokingly replied, "12 hours with Denver as the alternate.” I also asked for the weather in Denver.

There was no response. I circled awhile longer and then enquired about the weather and was told it was still "zero/zero." I asked if GCA was available. "They're supposed to be out there," said the tower.

I was cleared to a GCA frequency and started an approach. Since I held a "Green" instrument card, I had the authority to start an approach even if conditions were below minimums. At the time, those minimums at Lemoore 150 feet and ½ mile visibility.

I entered the fog bank at 1,200 feet and descending toward 150 feet, the controller directed a missed approach. Since I couldn't see the ground I gladly pushed everything forward and got out of there.

Lemoore had 13,000 foot runways and new strobe approach lights which, like illuminated jack rabbits, streaked towards the touchdown area on the runway. On my third GCA at 150 feet, I saw the strobe lights running along the centerline. On the fifth approach, I could see a centerline stripe. On the sixth, I landed. On roll-out, nearly 2,000 feet down the runway I ran smack into those ubiquitous zero/zero conditions again. I later surmised the accumulated heat from the Skyraider's R-3350 engine had warmed the air in the landing zone just enough to lift the fog a bit.

Thanking GCA, I switched to ground control and was advised the field was closed. I explained I was on the runway with virtually no visibility and required a "follow me" truck. After 10 minutes of standing on the brakes, I discerned a rotating beacon inching towards me along the centerline. The follow me driver was having as much trouble seeing as I was. He slowly turned around in front of me and I eased my A-1 with its 13 foot prop behind the truck. The driver later told me if he had felt the prop touch his truck he was going to floor board the accelerator and leave me in the fog. I followed him closely (uncomfortably so) into the VA-122 line to a spot in the front row. Hugh Hoy, VA-1's CO, as was his practice, met me that day with his trusty line mule, festively painted in squadron colors. He said, "I knew you were scheduled in, but I didn't expect you so soon."

Hugh dropped me off at the CAG-21 hanger where I bounded up to the top deck arriving at CAG Monger's office at 1005. Grinning, the CAG said, "You're late." The local squadron COs were there but the fighter guys from Miramar, flying Crusaders, didn't arrive until 1300, well after the Tule fog had lifted for the day.

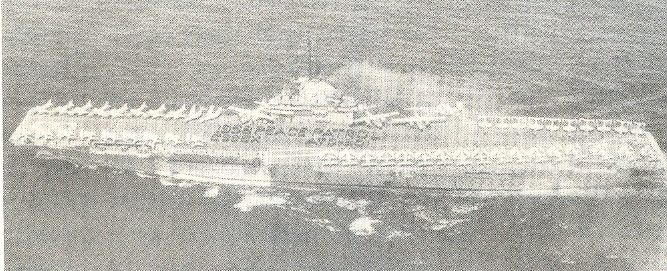

“Instanbul Incident”

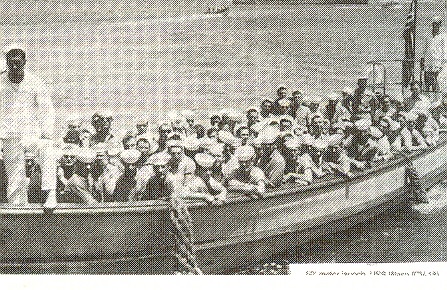

There was the usual four to six knots of current running south in the Bosporus, draining excess water from the Black Sea into the Mediterranean via the Sea of Miramar and the Dardanelles. USS Coral Sea (CVB-43), anchored in the stream, had launched all boats to recover its 1500 man liberty party from the fleet landing at Istanbul, a 20 minute ride to the west. Motor launch #4, a diesel powered 50 footer, was underway with a full load of white hats at 0100 on a dark, moonless, summer night in 1951. The launch, carrying a standard five man crew--boat officer, coxswain, bow and stern hooks, engineer--was loaded to capacity with 150 sailors in various states of exhaustion, inebriation, combativeness and exuberance. Some were quiet, some argumentative and loud, some were upchucking over the gunwales. Typical for hard working seamen deserving R&R.

The launch cut across the current at eight knots toward Coral Sea and approaching from abeam on her port side, the current caused the boat to slide astern. The coxswain held a heading 90 degrees to the ship's north-south orientation. I was the boat officer, a 22 year old ensign in VA-I5 on my first tour. I bore full responsibility for the launch. Standing alongside a 19 year old coxswain on the afterdeck, I told him to proceed well clear of the fantail because we got too close on a previous run.

Boat officer duties were assigned to the most junior air group aviators without any hands-on training. There were no written instructions, only verbal advice passed on by senior flyers which, in effect, was: "You're in charge; it's you're ass if anything goes wrong." Of course most of us Naval Aviators had egos and believed, "What the hell, if I can fly an airplane, I can handle a boat."

Some 100 yards out, the coxswain eased the tiller to the right causing the launch to head up into the stream and start across the carrier's fantail. The objective was to reach the after starboard accommodation ladder where, with luck, the human cargo would scramble safely up the ladder. The boat officer would report to the JOOD and secure for the night. The coxswain and crew would secure the launch to the starboard boat boom and also secure.

As the launch passed astern of the carrier the engine quit. Quickly losing headway in the strong current, the launch, unresponsive to its rudder, moved off with the flow of the Bosporus toward the Sea of Miramar.

"What happened!" exclaimed the coxswain. "How the hell would I know," I responded. Calls to the engineer 20 twenty feet forward with the engine were lost in the din of the assembled sailors.

"Quiet in the boat," I yelled. Sensing the situation, two chiefs, sitting quietly in the stern sheets, came forward through the mass of bodies, demanding quiet as they progressed. "The engine's leaking oil," shouted the engineer, explaining why it was shut down. "I have standing orders to shut the engine down at the first sign of an oil leak."

"How bad is it?" I asked.

"I can't tell but there's a lot of oil here," he said. The launch was now totally without power. The bow gradually swung around to the south and we drifted along like a cork in a stream away from the city lights and into the blackness of the night.

"Where's the Aldis lamp?" I demanded? We had to alert the ship.

"We ain't got none," said the coxswain.

"A flashlight?" I asked, and the coxswain sought one. Minutes passed as I mulled the situation. I was responsible for this boat and the 150 people in it. The ship didn't know we were in trouble. I wondered how long it would take for us to be missed. Many of the sailors are drunk and sick. How long can I keep them in their seats? I can no longer make out the outline of Coral Sea. She has blended into the dimming skyline of Istanbul.

I remembered preflight lectures that warned an engine without oil will freeze up in minutes. The longer we drifted from Coral Sea, the longer we'd have to run the engine.

Almost without conscious thought, I barked, "Engineer, start that engine."

"Sir, I have standing orders to shut it down with an oil leak," he said. Now convinced I would stand or fall with my decision, I stated, "Engineer, this is a direct order, start that engine … NOW!" The engine roared to life.

"Coxswain, make straight for that after starboard ladder," I said.

"Aye, Aye, Sir," came the response as he rang up one bell, meaning engine ahead slow.

"Give it four bells. With this current, we have no other choice."

He sounded four bells, the engine went to full power, the launch quickly picked up eight knots, an advantage of four against the current. I reckoned we had been adrift 25 minutes. If the current was running at no more than four knots, as I hoped, it would take us about that same time to get back to the ship. On the other hand at five knots it would take over 30 minutes. How long will that engine run? I figured running it at high RPM for a shorter time was better than lower RPM over a longer time.

"Sir, do you think we'll make it?"

"We're in God's hands now, keep your fingers crossed." I said. One of the chiefs handed me a flashlight, I aimed it at the island and flashed a series of SOSs but got no response. I focused the light toward the JOOD's station at the top of the accommodation ladder as the launch approached the ship's starboard quarter. With the chief's help I ordered the engineer to cut the engine as soon as we reached the foot of the ladder, I breathed an immense sigh of relief when the launch glided smoothly up to the landing. The engineer shut down the engine. The sailors, quietly, orderly, and sobered up made their way up the ladder and the security of their ship. I followed, lastly.

I asked the JOOD if he'd seen our distress signals.

"Distress signals? No, what's the problem?" he said.

"Damn, we could have been halfway to the Med by now!" I said.

"What're you talking about?" he said. Restraining my anger I reported launch #4 out of service due to engine problems. It was after 0200. I secured to the JO's bunk room.

Next morning, after quarters on the flight deck, somewhat blurry eyed, I was sitting in the ready room reading the dispatch board.

"Where's Carlton?" came a loud voice. It was my CO, CDR John Lacouture.

"Here, sir," I said.

"The Chief Engineer wants to put you on report for disregarding his standing orders. What's your story?" he asked.

I explained what happened, emphasizing my concerns about the current, the darkness and the safety of the liberty party.

After a few moments the skipper said, "Well, running that engine was a risk, but it gave you a shot at getting back and a chance to alert the ship as well. If you had lost the engine, you would have been no worse off than before." Turning abruptly to leave the room, he declared, "I'll take care of this." And the incident never came up again.

I have often wondered what would have occurred had I followed the Chief Engineer's standing order. Importantly, John Lacouture (later CAPT) had a fundamental impact in shaping not only my flying skills, but my approach to decision making as well. As I look back and reflect on this incident, I have no doubt that he was there with me that night when I ordered, " … start that engine!"

“Flying with a Bent Wing” *

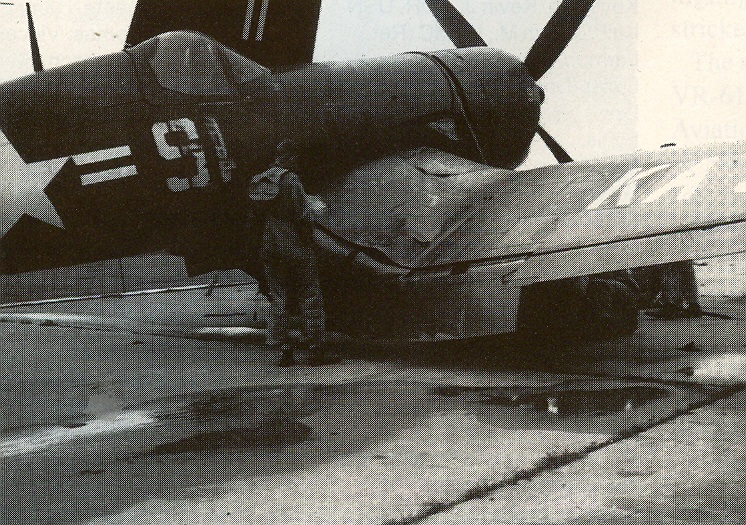

The F4U Corsair had many nicknames: U-Bird, Hog None, Hog, Widow Maker, Bent Wing, to name a few. Ungainly looking on the ground, particularly with flaps down, wings folded and cowl flaps open, she cleaned up beautifully in flight, presenting an unsurpassed elegance. With inverted gull wings (designed to reduce the length of her main landing gear struts and to provide a 90 degree interface between fuselage and wing) her airborne silhouette was unmistakable.

I first met the Corsair, up close and personal, in late 1949 at NAAS Cabaniss Field, Corpus Christi, Texas. As Flying Midshipmen, Bob Aumack, yours truly and Ed Crow, had completed basic flight training with 200 hours in SNJs and were fresh from making our first carrier landings (six each) on USS Cabot (CVL-20) off Pensacola, Florida. After finishing carquals we became advanced flight students, selected to fly Corsairs and promoted to First Class Midshipmen. As such we had earned the right to wear brown shoes and the distinctive aviation green uniform.

Upon reaching such exalted status, each Midshipman stood several inches taller and also commanded respect from the Marine gate guards as well. The Corsair, a mainstay of Naval Aviation from 1942 through the Korean War, would soon bring a large measure of reality back into their lives. Those Wings of Gold were yet to be earned, requiring 100 hours in the F4U-4 and another carqual session with the Cabot.

Over the next several months the three Flying Midshipmen successfully met the challenges of the F4U syllabus at Corpus. Comfortable and confident in the Corsair, having flown day and night tactics, rocket, gunnery, bombing and instrument flights from the deck to 38,000 feet, Aumack, Carlton and Crow were ready for the last phase of flight training—carquals at Corry Field, Pensacola.

The Corsairs used by Carrier Qualification Training Unit Four (CQTU-4) rarely flew above 1,000 feet. They were used day in and day out for Field Carrier Landing Practice (FCLP). The "bounce" pattern for the Corsairs was usually set up at Bronson Field, an outlying airstrip. Typically, six to eight Midshipmen would fly to Bronson from Corry early in the day, while two or three flights of six each rode a bus to the field. The LSOs flew to Bronson, thereby providing spare planes for the session, which usually lasted four hours. The planes were rarely shut down because as each pilot completed the required number of approaches and landings (six to eight), he taxied off the duty runway and, with the engine idling, exited the bird and another pilot jumped in - "hot-seating." We merely sat on the parachutes and didn't attach the harness as bailouts from an FCLP pattern were unlikely and the attached chute would be inhibiting should a scrambling exit be required. Each student flew two hops a session. Those lucky enough to be on the last one, got to fly back to Corry while others rode the bus.

While carrier landings have always been recorded, at that time field landings were not. Thus, no one knew exactly how many field landings any plane or pilot had actually made. Most likely, the planes assigned to CQTU-4 made more than most aircraft assigned elsewhere. In our initial briefings we were enjoined to focus on the main wing spar sections, visible from the wheel wells, during preflight inspections. Hairline cracks were appearing along the spars. If the cracks had been "stop drilled," they were OK for flight. Stop drilled cracks had a small hole drilled at the very end of the crack. Most of the cracks started beyond our limited view from the wheel well and we were told not to worry about that end! If the crack had not been drilled, we were to down the plane. Most of the planes had multiple cracks. None of us asked how many cracks were too many. We had faith.

On April 27'h, 1950 Bob Aumack was in the bounce pattern at Bronson Field. A group of us onlookers gathered near the LSO station to observe the approaches and landings. Bob, on his first hop that day, made three landings when things changed a bit. His approach was steady, starting slightly fast, nose a bit low in close, followed by a cut. He made a three point landing on the centerline, added full power and took off.

From Bob's view all was normal. But from the LSO's platform, apparent also to the observers, Bob was in serious trouble. As Bob's Corsair touched down, the right wing had twisted and dropped, causing the fully extended flaps to come within inches of the runway surface. As Bob added power, gaining speed and lift, the wing twisted so that the leading edge was elevated, causing the plane to roll left. Bob needed full right aileron and rudder to keep the bird level.

There was no doubt in the LSO's mind that the spar had broken. He radioed Bob to climb straight ahead and to leave his landing gear and flaps down, thinking that any change in their positions might cause the wing to sever completely

All appeared to be going well as Bob flew straight ahead to 5,000 feet. All planes in the pattern were ordered to land and clear the runway. The LSOs huddled, discussing what to do next. As Bob was headed straight away, the imperiled Corsair grew smaller and smaller against the blue sky. He was advised to start a very gentle left turn back toward the field. Bob had his hands full. Struggling to keep the bird level required considerable right aileron and rudder control against the excess lift coming from the damaged right wing. At the same time he was fully engaged in getting into his parachute harness, no small feat in the Corsair's tight cockpit under any circumstances.

The conference on the ground continued as Bob could see and feel that the right wing was indeed abnormally aligned. He was able to fly with gear and flaps down, in a wide orbit around the field at 5,000 feet. After 45 minutes the decision was made.

One of the LSO's transmitted, "It's your choice, bailout or try to land."

Bob sucked it up a bit and elected to try the landing. After all, we were taught that bailouts were a last resort. But if that wing came unglued below 1,000 feet there would be no resort left. All eyes were on Bob and his wounded Corsair as he made a wide, straight in approach.

We knew there was no turning back for Bob. Would that bent wing bird hang together? He was steady as a rock as he came on in and flew steadily over the fence and the runway threshold. His touch down was picture perfect as Bob held in aileron and rudder against the persistent pressure from the damaged wing.

On roll-out, as speed paid off and the tail settled, the damaged wing, permanently twisted, again caused the flaps to come within inches of the runway. It was later determined the spar had indeed broken and that the wing skin alone was holding the aircraft together. That week-end the following appeared in the Corry Field plan-of-the- day: "Congratulations to Midshipman AUMACK for the fine job he did Thursday. He may not have his wings yet, but on that particular hop he flew like a veteran. Even Grandpaw Pettibone would approve."

Subsequently, Aumack, Crow and yours truly successfully carqualed and earned those golden wings. Bob Aumack, incidentally, eventually became the CO of the Blue Angels.

* George Carlton, Wings of Gold, Spring 2001; © 2001.

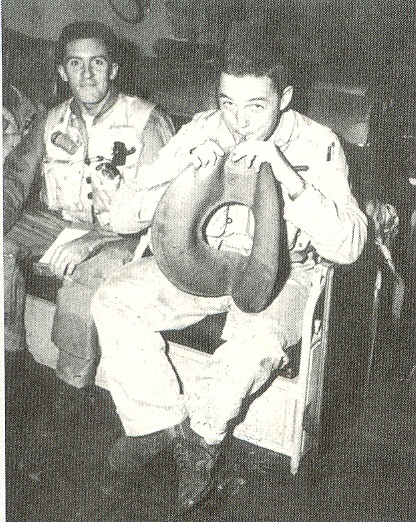

“Donuts” *

The Douglas AD (A-1) Skyraider was designed to be the fleet's first line dive bomber, but it proved it could also deliver tactical nuclear weapons. With the development of tactical nuclear weapons in the early 1950s, the Navy scrambled to provide a carrier- based capability. The North American AJ Savage became the Navy's answer to the USAF's high flying B36. Analysts soon determined that anything flying high in the sky was easily detectable and therefore easily countered. Low level, nap-of-the-earth, flying proved to be the best way to penetrate enemy territory by remaining beneath early warning radar detection. ADs flew well at very low altitudes even with a MK7 "nuke" on its centerline station plus two 300 gallon external fuel tanks on the inboard wing stations. The Skyraider's radius of action from the carrier was over 2,000 miles, limited primarily by oil consumption. It could stay aloft from 12 or more hours.

On low level (50 to 100 feet above ground level) training missions, lasting between eight and 12 hours, the pilot's posterior, strapped tightly to the parachute seat cushion, became uncomfortably numb. The solution, attributed to a CAG-8 flight surgeon, was to supply AD pilots with medicinal donuts--round, red, rubber, inflatable inner tubes to provide relief following rectal surgery and such. The best ones were equipped with hand squeezable plungers which allowed the pilot to vary the inflation pressure from time to time. Some referred to them as donuts, others as whoopee cushions. They proved to be a godsend on long flights. Of course the Skyra ider flyers endured considerable ribbing from air wing shipmates.

On low level (50 to 100 feet above ground level) training missions, lasting between eight and 12 hours, the pilot's posterior, strapped tightly to the parachute seat cushion, became uncomfortably numb. The solution, attributed to a CAG-8 flight surgeon, was to supply AD pilots with medicinal donuts--round, red, rubber, inflatable inner tubes to provide relief following rectal surgery and such. The best ones were equipped with hand squeezable plungers which allowed the pilot to vary the inflation pressure from time to time. Some referred to them as donuts, others as whoopee cushions. They proved to be a godsend on long flights. Of course the Skyra ider flyers endured considerable ribbing from air wing shipmates.

Following the deployment of VA-25 in Coral Sea in early 1968, the last Navy "Spads," as they were then called, were turned over to the USAF and the Vietnamese Air Force. Whoopee cushions/donuts went along for the ride. Here's an account by USAF pilot J. A. Guthrie Jr., USAF:

"Early in 1968, a bombing ban was finally lifted from the Plain-de-Jars region of Laos, and I was scheduled for my first A-1 E Skyraider mission. My wingman, Ralph Hoggatt, was a bona tide hero, distinguishing himself during a search and rescue in the Mu Gia Pass region the previous November, but we were apprehensive about our first incursion into this known hot spot. Informed that the Plain would be heavily fortified, we listened intently to the briefings, paying particular attention to possible locations of antiaircraft gun emplacements.

Flying as lead for ‘Firefly’ flight, I lead our sortie into the area without incident. We decided on the best run-in headings and escape route, and rolled in to drop a MK82 500 pound bomb. The enemy responded with little ground fire. So far, so good.

But, as I pulled out from the initial pass, I heard a loud explosion and felt a strong concussion under my posterior--every aviator's nightmare. I was hit in the most vital area! In cold sweat, I relaxed stick back pressure to relieve g forces and conduct a quick investigation. My frantic self-inspection sent the aircraft on an erratic flight path and triggered a radio call from Ralph, asking if I was in trouble. I was too focused on my highly motivated examination to respond. No blood, no pain. I'm definitely not going to be singing soprano. Good! Very, very good!

I pulled up and climbed to a safe altitude, then tried to figure out what the hell had happened. Instead of an ejection seat, the A-1 used a Yankee extraction system that pulled the pilot from a disabled aircraft. The seat was a solid "hard pan," and after three hours airborne a pilot's tail section would really suffer. As a result, many of us sat on donuts--the inflatable inner tubes liberated from hospital hemorrhoid patients.

But constant usage in an environment for which it was not designed tended to shorten its life span. Just as I pulled off target, age and repeated ‘g’ loads combined to produce a massive whoopee cushion failure. ‘G’-compressed air had blown a hole the size of my fist through the inner tube. During my flight back to Udom, Ralph, worried that I had been hit, repeatedly asking about my condition. In a most resolute baritone I replied I would explain once we were on the ground. It was clearly a memorable moment of a Southeast Asian combat tour.

[Note: The AD was originally designed without an ejection seat. The ‘Extraction Seat’ used in A-1 Skyraiders during the Vietnam War was called the "Yankee Seat’" It was, technically, the Tractor Rocket Extraction System. Developed by Bob Stanley, a test pilot for Bell Inc., the system essentially consisted of a rocket and a long lanyard designed to pull a pilot from a stricken airplane. In distress a pilot could start the sequence by blowing the canopy which in turn fired the rocket while releasing the pilot from the safety belt. Thus, the pilot was yanked clear of the airplane. Parachute opening followed shortly thereafter.

* George Carlton, ‘Tale Winds,’ Wings of Gold, Spring 2004; © 2004.