Surviving the Purges

Surviving the Purges

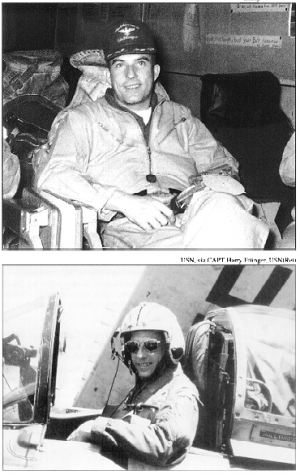

“The base closings were amazing,” CAPT Ettinger reflects today. “Everything was closing very rapidly.” In that environment, harry and his classmates learned the basics of Navy Air from the ground up – painting buildings at Mainside Corpus while outlying fields were being shut down. Prospective Golden Wingers were given every opportunity to get out, and many accepted. Harry survived two “purges” in which budding careers were nipped by the expedient of a coin toss. “Both guys with lockers to my left and right lost out,” Harry recalls, summarizing, “Of the 212 of us who started, 18 got our wings.”

After mastering the mighty Stearman N2S biplane, AvCad Ettinger went on do demonstrate proficiency in SNJs, SNBs, PBMs, SB2Cs and finally TBM Avengers. His initial carqual was aboard the brand new USS Wright (CVL-48), while his TBM checkout was aboard her sister Saipan (CVL-49). With that huge wing and low landing speed, Harry found the "Turkey" was not difficult for a fresh-caught aviator. He pinned on his wings and ensign’s bars at Pensacola on 1 July 1947.

Assigned to VA-6A at NAS Seattle, ENS Ettinger and two others volunteered for a special photo project at San Diego. Shortly they fetched up in Rendova (CVE-114), equipped with camera-laden TBMs and F6F-5Ps, and with that he embarked upon the adventure of a 1948 world cruise. That was the good news.

The bad news – the first priority was to deliver a stem-to-stem deck-load of AT-6s to Turkey, which meant no en route flying. "We had great liberty," Harry enthuses, with stops at Suez, Ceylon, Singapore, the Philippines and Hawaii. However, he and Hellcat pilot Bob Vermilya (Where Are They Now: Bob Vermilya, The Hook, Su '94, Page 13) would have preferred a bit more flying:

"We got five traps in the Persian Gulf, where we photo-graphed the area, and finished the three-month deployment with a total of ten." By then Harry was more than ready to return to the West Coast and his bride, Jean.

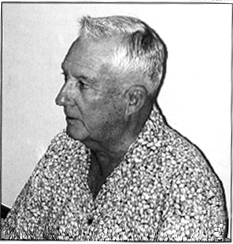

The next year, 1949, the squadron (now VA-55) received "some very old" AD-1 Skyraiders. However, new AD-4s were soon on hand, and the high-altitude capabil-ities were put to use at the expense of the Air Force. Those were the days of the B-36-versus-carrier debate, and VA-55 undertook to demonstrate which was superior. Harry and his squadronmates cheerfully intercepted some Peacemakers – much to the chagrin of the blue suiters.

At the end of 1943, 17-year-old Harry Ettinger of Milford, Mass., was preparing to go to war. So were the other 59 boys in his high-school class. For that matter, so were some of the girls, who joined the WACs or WAVES. Harry and two others were intrigued with Naval Aviation ("We never gave a thought to the Air Force") and were accepted into the V-5 program, which "stashed" them for one year at Williams College. Sworn into Uncle Sam's Navy in January 1944, the boys were slated to begin training in 1945. Harry had been exposed to the sea services early in life when the Coast Guard Auxiliary whetted his appetite for salt water. Upon completion of a year of college, Seaman Ettinger went to Ferry Service Squadron One, but his pre-flight class date kept slipping. Finally he got “The Word”: starting date October 1945.

Apparently, the Imperial General Staff in Tokyo also got The Word and hastened to capitulate on 2 September.

In March 1950 Harry's Naval obligation ended and he was released from active duty. With a family to support, he found work as a flight instructor and, ironically, as a Convair electrician working on B-36s! A nascent American Airlines career was cut short when he was suddenly recalled to active duty in October, four months after the Korean War erupted.

His Own Detailer

Reporting to Air-Pac, ENS Ettinger was offer a slot in VC-3 at Moffett Field, where they flew Banshees and Corsairs. Preferring to remain in San Diego, he asked what was available locally and was advised to look at VC-35 and VC-11, both flying Douglas Sky-raiders.

Today, Harry chuckles at the recollection: "I was my own detailer!" He took one look at VC-11's AD-3W "Guppies" and decided he didn't want to fly anything

that ugly. So VC-35 it was – CDR Charlie Stapler had recently turned the squadron into the night-attack specialists for AirPac. Transition courses and an instrument class at Barbers Point completed the curriculum.

storm, arriving at a cave complex near Wonsan. There "a tall, impressive looking guy in civilian clothes" took over. He told the aviator that a release would be arranged, provided Harry talked to the U.S./ROK rescue team by radio telephone. Harry figured a trap was being set, but took advantage of the fact that nobody overheard the full conversation. With the receiver to his ear, Harry could control the conversation and shield some information from his "handlers." He did not know the identity of the American on the other end, but arranged a "waveoff" signal in case of a trap.

More than 30 years later Harry learned the details: A U.S. Army unit on a nearby island was running guerrillas throughout North Korea. However, as he suspected, the operation was badly compromised, and nearly all the guerrilla teams were killed or captured during the war.

An Escape – And Captured Again

However, at the appointed time and place an H03S flown by CPO Duane Thorin motored into the pickup site. Thorin was the best possible choice: He already had some 120 peacetime and combat rescues to his credit. However, his passenger was an army lieutenant of dubious credentials who insisted on taking a heavy load of supplies on the rescue flight. With a Valley Forge ResCAP overhead, the helo alit and the officer pulled the 90-lb. Ettinger inside. Thorin lifted off with difficulty, flew over the lip of the ridge, ran out of ground cushion and crashed. The extra load had scuttled the chopper. Another rescue effort by a Marine Corps helo failed, and Harry Ettinger was again a guest of the commu-nists. He suffered a relapse, but two weeks later returned to Pyongyang.

In retrospect, Harry suspects that the communists wanted the rescue to succeed as a means of gauging U.S./ROK methods. If so, the plan backfired. Harry subsequently went to a remote, primitive camp near the Yalu where at least he could wash. "On August 8th, 1952, I washed my hands for the first time since December 13th."

Though there was no physical abuse, the mental and emotional pressure increased. The communists were eager to obtain "confessions" of germ warfare activities and told Harry and his hard-nosed holdouts, "You confess or you don't go home." That in itself was welcome news, as it indicated negotiations were proceeding. Sure enough, Harry and his "dirty dozen" colleagues were held until 10 days after the armistice, having received "pardons" for their "crimes."

Now LT Ettinger returned to U.S. control in August 1953, one of only 21 Navy pilots or aircrew and 10 corpsmen among the 4,418 returnees. At least 2,722 others had perished in enemy hands, and it is not known how many of the

8,177 MlAs died as prisoners or were transported to Russia. The Eisenhower administration chose not to pursue the matter.

Harry was delighted to learn that his two crewmen survived their ordeal, and his POW status had been reported to Jean. Squadronmate Marv Broomhead had been released earlier in "Operation Little Switch," reporting that Harry would be coming out in "Big Switch." Harry and Jean were reunited in San Francisco.

Back In the Saddle

Following a stint at Balboa Naval Hospital, Harry checked his options with AirPac personnel. Though still USNR, he wanted to remain flying tailhook airplanes. However, he ran afoul of two JG flight surgeons who declared that with fluid in his lungs he was only suited for Group III duty. LT Ettinger felt no need of a co-pilot and took his case to the senior medic. "I don't remember his name," Harry says, "but he'd been the flight surgeon aboard Valley Forge! He listened to me and said, ‘You look pretty healthy to me!’”

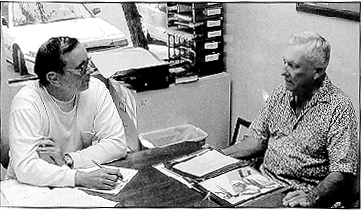

Harry had no problem with a T-33 jet instrument checkout ("I had more trouble learning to drive again") and began a terrific job in the Miramar ops office. For two years he flew everything available, both props and jets.

Harry Ettinger returned to the fleet via VA-56, flying F9F-8 Cougars during a Bon Homme Richard (CVA-31) WestPac. A non-flying "pay-back" assignment as first lieutenant of Lexington (CVA-16) brought him into close contact with the black shoe world, running hull, anchors and boats departments. However, while there, Harry's request for a regular commission was approved by CAPT James R. Reedy, and he made 0-4 the same day.

A perceived shortage of aviation ordnance resulted in LCDR Ettinger's assignment to the supply depot at Mechanicsburg, Pa. Once free of that chore, Harry consulted with his detailer, requesting AirPac A-4s. However, his Skyraider experience reared its head. With more traps in props than jets, Harry was sent to the A-1 RAG at Lemoore. Requalified in the Spad, he joined VA- 25 as Ops 0 for Midway's (CVA-41) 1963-'64 warm-up cruise for the Southeast Asian Thing. “On the last day of the deployment we delivered our planes, minus carrier and nuke gear to Bien Hoa for the South Vietnamese Air Force."

Harry’s Third War

The next cruise was for real. After deploying in April 1965, Harry fleeted up to CO and moved on with his second war. In 1,850 sorties totaling 8,500 hours, VA-25 lost two pilots and one aircraft. It could have been worse: As much

as six and a half hours per sortie, day and night was a rough way of making a living. Yet Harry says things generally went well under CDR Bob Moore, "a wonderful guy."

Some comparisons with Korea were inevitable. Harry recalls that night flying especially was improved since "the angled deck changed the whole Navy." There had been no SAMs in Korea, but the SA-2s seldom bothered the Spads, while 37mm remained a potent threat. CAG Moore believed in rotating mission leads, and on those occasions when the A-1 skipper had the duty, “the jets just had to wait for me to arrive!”

Apart from some hair-raising ResCAPs, the highlight of the cruise was Clint Johnson and Charlie Hartmann's bagging a MiG-17. While the Phantoms of VF-21 had logged the first two MiG kills, the piston slappers wasted no time lording it over the other go-fast types of CVW-2. Harry called down to the F-4 ready room, asking “Can we borrow your MiG stencil?” He reckons his boys received congratulatory messages from every A-1 squadron or detachment in the

Known universe.

On one ResCAP Harry saw more MiGs than most fighter tigers did in the entire war. He witnessed two MiG 19s bag an F-104 near Hainan Island, then diverted inland to rescue a down A-4 pilot. In the process two MiGs from Kep blew through the area, but the Spads remained on station until an HC-1 chopper made the pickup, recovering with the fuel warning light strobing.

Subsequently Harry made two more Tonkin Gulf cruises with CarDiv Nine staff, including the horrific Oriskany (CVA-34) fire in 1966. Ending the stint as a captain selectee, Harry reluctantly acceded to ADM Mike Michaelis’ advice, “You need a D.C. tour.”

All things considered, CAPT Ettinger got off lightly. Following Naval War College he joined the joint staff back-room boys in analysis and war-gaming. “It was really fun,” Harry enthuses. “I was the Russians in RISOP games with ICBMs, bombers – the whole thing.” Each evolution took 18 months to plan and six months to game, going head to head with the U.S. SIOP. “I liked it so much that I even went in for half days on Saturdays,” Harry explains. “The first thing I did was blow up NORAD.” He reckons that eventually he targeted every Holiday Inn across the fruited plain, just to make sure he nuked enough dispersal airfields.

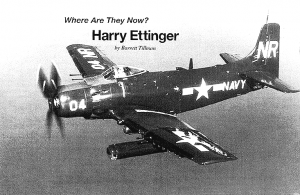

Harry’s last assignment was a year in Material Command before retiring in September 1974. By then, he and Jean were dedicated Californians, and they settled in Cardiff by the Sea, a lovely community just north of San Diego. A three-

year remodeling job occupied much of their initial retirement time, but more recently they keep busy traveling, attending POW events, and following the Padres to spring training.

Harry keeps in touch with his Tailhook Association friends and only rarely misses the annual gathering over the years in Las Vegas, San Diego and Reno. Wherever he is, he is at the center of the action. His jovial, easygoing manner and ready smile are an identifiable trademark – as his many stories. Life is much easier now for Harry than it was in the early days, and it’s obvious he enjoys like in Southern California.

It’s a long, long way from “Pox Palace” and Pyongyang.