Not yet 1

My granddaughter, a student pilot and aviation enthusiast, walked beside me as we toured the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

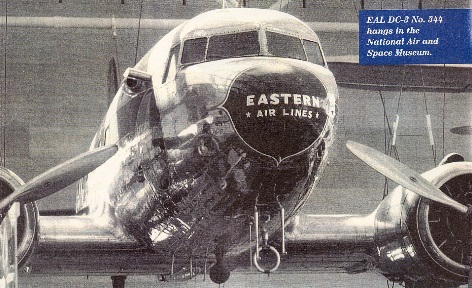

Hanging from the ceiling in front of us was No. 344, a DC-3 with Eastern Airlines colors and emblems.

“Grandpa, wasn’t that your airline?” she asked excitedly.

I nodded and kept staring at the right cockpit window.

“Did you fly that old airplane?” she inquired with a frown.

“Yes, I flew that airplane on Christmas Eve in 1951.”

“Tell me about it, please.” She asked.

“Well, we were headed for Chicago. The weather was awful. Rain was turning to thunderstorms and fog. Chicago was forecasting snow by the time we were scheduled to land. A line of thunderstorms was preceding a weather front by 40 miles. Capt. Frank W. Hill made the landing at Louisville by spotting the runway at the last moment of our approach in heavy fog.

“The next leg was my time to fly. That airplane, old 344 hanging up there, as I said, was the one we were flying. As soon as we took off, I knew we were in for a very rough trip. The turbulence was heavy. As a new copilot, I was doing my best to hold the airplane level and on course. About half way to Indianapolis, we flew into the worst of the weather. We had no radar to show us where the thunderstorms were or automatic pilot to hold the wings level. The lightning was blinding me. The hail hitting the nose of the airplane was deafening to my ears, and it was almost impossible to hold the airplane on course.”

“Were you using the omni stations for navigation?” She inquired.

“No. We did our navigation by listening to the low-frequency range leg that extended south from Indianapolis. Most of it was a guess because the static the storm produced was drowning out the radio signals we used for maintaining our course.”

“What’s a range leg?”

“Two radio transmitters near the airport at Indianapolis sent out different signals. If we were to the left of course, we heard a dit dat. If we were to the right of course, we heard a dat dit. If we were on course, the two signals came together as a continuous hum.

“The company radio operator in Indianapolis called to report the airfield there was closed because the new instrument landing system had failed and the ceiling was too low for a low-frequency range approach. After checking the weather in Chicago and Milwaukee, Capt. Hill told them we were preceding to Midway Airport in Chicago.”

“Didn’t the weather forecaster tell you about the weather?” She asked.

“We had gotten a good briefing before we left Atlanta, but in those days the captain was usually a better forecaster than the weather department.

“The turbulence eased off a bit, but the rain had turned into snow. When the captain reported our position over Lafayette, Ind., he was informed that all landing air facilities were temporarily out at Midway. We refilled our flight plan for Milwaukee. About 30 miles south of Midway, we were informed that Milwaukee’s weather was below landing minimums in heavy snow. The captain checked our fuel supply and shook his head. Then, out the left window, he saw a hole in the clouds below us.

“’Tell Midway Tower that we will be making a Cicero Avenue approach to Runway 33,’ the captain said. Then he told me to let down to 800 feet and fly a heading of 345 degrees.

“A few minutes later he reported to the tower controllers that we were passing the Blue Island Tank. They cleared us to land if we could find the runway.

“’Let down to 400 feet and fly 350 degrees,’ the captain ordered.

“I had to wipe the palms of my hands on my pants leg every three minutes to keep them dry.

“’Slow it up to approach speed and fly 355 degrees.’ He lowered the flaps to approach position.

“I glanced at my palms to make sure that it wasn’t blood that was coming out of my hands instead of sweat.

“’Five blocks to go,’ the captain said from his position with his face against the left window so he could count the streets that cross Cicero Avenue.

“’Let down to 200 feet and keep her slowed up.’

“I was measuring altitude in inches and speed in yards per hour. My heart was beating so loudly in my ears that it was hard for me to hear anything else.

“’I’ve got the airplane,’ the captain announced. ‘Lower the landing gear and give me full flaps.’

“As he took over the controls, he rolled old No. 344 into a 30-degree left bank and pushed the nose over to line up with the straight-in approach to Runway 33. The landing was smooth as glass.

“I think I looked at him as if he were God himself.”

My granddaughter and I walked on to the next exhibit.

She turned to me and said, “Grandpa, I used to think you stretched your stories about your flying days a little, but I think it would be hard to stretch any story about flying that airplane through a bad storm with no radar or autopilot.”

I smiled and nodded. She didn’t seem as interested in the other exhibits. She kept stopping to stare back at No. 344 with an occasional glance at me.

A few days later I was back at my German Shepherd kennel in southern Arkansas tending to my Muscadine vines that would yield grapes so I could make excellent wine next fall. My portable telephone rang. The voice from the speaker said, “This is the man upstairs calling you.” My knees became weak and my heart skipped a beat.

![Capt. Oel Futrell, a retired Eastern pilot, landed his last DC-10 flight on Christmas Eve [1986] exactly 35 years after flying No. 344.](/sites/default/files/Oel%20Futrell1.jpg) The voice continued, “If you will look up, you will see a United Air Lines B-737 headed south. Your two nephews are flying as passengers from Chicago to Mexico City. Watch our turn to the left.”

The voice continued, “If you will look up, you will see a United Air Lines B-737 headed south. Your two nephews are flying as passengers from Chicago to Mexico City. Watch our turn to the left.”

After stuttering a few sounds into the telephone, I saw the Boeing 737 turn 30 degrees to the left, then proceed on course.

I just thought we would say hello on our air phone as we passed by,” Capt. Ken Futrell said. He had made captain at United when he was 30 years old. Andy, his younger brother, had followed Ken to United and was serving as his first officer.

I watched the airplane disappear into the clouds to the south and turned my face to the eastern sky and said, “Thank you, Lord. You know I didn’t stretch that Cicero Avenue Story; and besides, I’m just not ready to go—yet.”

1 Capt. Oel Futrell (Eastern, Ret.); Air Line Pilot March 1995.

“Moon over Miami”

April '49. Jack Daubs (10·46) and I were assigned to VP-23 at Masters Field in North Miami. We were brand new Ensigns and with the pay raise from that of a Midshipman, we each bought a red convertible.

Our skipper had just made full Commander and was bucking for Admiral before he retired. To further his career, he never missed an opportunity to 'brown nose' the brass and invited anyone from Washington to come inspect his squadron and stay at the big, beautiful home he rented on Miami Beach.

One Friday morning, Jack and I were called to the C.O.’s office and ordered to show up that night at his residence in dress whites for dinner. A two-star from BUPERS with wife and 2 teenage (18 & 19) were spending a couple of days as his guests. We were directed to be on our best behavior and display impeccable manners at dinner.

After dinner, the two daughters asked the skipper if his two Ensigns could show them the lights of Miami Beach at night. He wasn't real enthused with the idea … but they insisted. After promising that we would have the girls back by 2300, we drove down Collins Avenue with the top down.

The girls were not really interested in the 'lights'; they wanted the 'sand' on a deserted beach. Eleven p.m. came, as did midnight … and 0300. No matter how much Jack and I 'begged and pleaded' those two girls could not be herded back into my car and returned to the skipper's house … they were Navy brats and knew all the angles.

At 0600, we pulled into the driveway … I swear there was smoke coming from the C.O.’s nose and ears. Right there he promised us at least a month in solitary, plus expulsion from the Naval Service. The Admiral's wife tried to come to our rescue by explaining that her daughters had insisted on the night on the beach and that the two Ensigns were only doing their duty to protect them on that dark, lonely sand.

Monday morning, Jack and I stood for an hour at attention before the skipper permitted either of us to utter a single word. He must have really zapped us in our fitness reports because a few months later Jack and I got our orders releasing us to civilian life while other Middies in the squadron went on to Navy careers.

Jack got his PhD from Penn State and flew as a captain on 747's with TWA. I got a degree from the University of Miami and flew for 35 years with Eastern Airlines.*

Three weeks before he died of cancer, Jack and I enjoyed a fun-filled conversation and reminisced about that night on the beach with the Admiral's daughters … Thanks girls, for a wonderful life flying for the airlines!"

* Oel flew the last commercial flight in the DC-4 hanging in the Smithsonian.