“The Sea Voyage of ‘Pelican 8’”

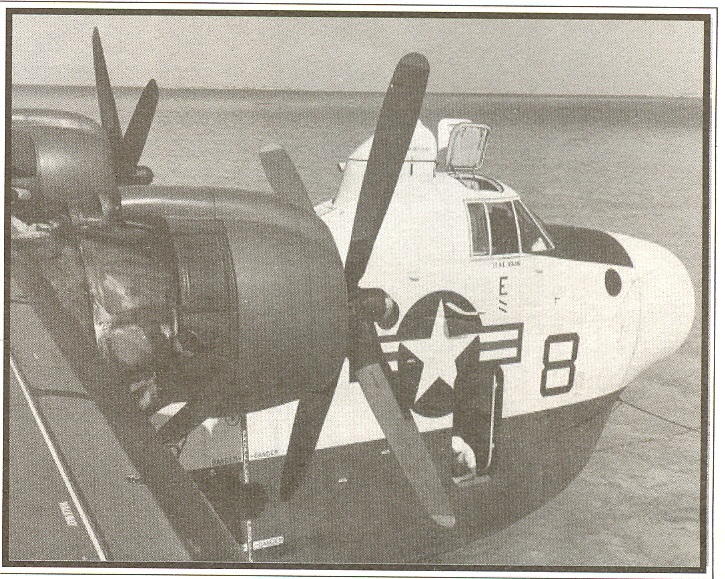

Over the years, I have worn my miniature Navy wings on my lapel proudly announcing that I was once one of the proud band of Naval aviators. Needless to say when people I meet see the wings I am asked "What did you fly?" I can see the visions of Tom Cruise in "Top Gun" in their eyes and when I reply seaplanes, PBMs and P5Ms, their bubble bursts and they reply "Oh, the old Catalina". I then reply "I have heard of the Catalina but I never flew one." Then they want to know, "Why did you ever want to fly seaplanes?" (that's assuming that they ever heard of them of course).

Over the years, I have worn my miniature Navy wings on my lapel proudly announcing that I was once one of the proud band of Naval aviators. Needless to say when people I meet see the wings I am asked "What did you fly?" I can see the visions of Tom Cruise in "Top Gun" in their eyes and when I reply seaplanes, PBMs and P5Ms, their bubble bursts and they reply "Oh, the old Catalina". I then reply "I have heard of the Catalina but I never flew one." Then they want to know, "Why did you ever want to fly seaplanes?" (that's assuming that they ever heard of them of course).

The number of us 'Ancient Mariners' is rapidly diminishing. This keeps me current on how old I am. It's a short story about a "Flying Midshipman" who wanted to get his wings and out to the fleet post-haste and selecting PBM training was the answer to that prayer. The other choice had long stays in "pools" as the waiting groups were known. There was a time in my career when this choice was beneficial to my survival in the human race. I will now elaborate on such a bold statement.

It was February, 1960, and our squadron, VP-44, flying P5Ms out of Norfolk was finishing an exercise in San Juan, Puerto Rico known as "Operation Spring-Board" where we got the chance to strut our stuff and do things that we were trained for. We were an antisubmarine squadron with a secondary mission of mining. We had fired 5" rockets at smoke lights and flown formation as we mined imaginary harbors. We also had played tag with our submarines, conventional and nuke, during the two weeks we were there. These were the days when the Russian "Whiskey" class submarines were prowling off the Atlantic coast watching our maneuvers and ASW (Antisubmarine Warfare) was of prime interest to the powers to be. Our crew 'ran-over' what we thought was a "Whiskey" on a routine flight one day but when we went back he was long gone. She looked like a double prow barge without a tow. That's why we went back. (Another story for another time.)

Another diversion which had later implications: I was invited to ride a Nuke attack sub for a contest of skills between it and a Destroyer. The challenge was made at a bar in San Juan the night before between the skippers of the sub (name forgotten) and the USS Abbott--a DD with a Flag aboard. As I went aboard, I noticed the absence of brass to be attended to as on other navy vessels. I was informed by a crew member that they weren't allowed to even allowed shine their shoes because of the fumes and there was one person assigned to test the air quality at all times. I guess that's a good reason to go submarine but the chow is a better reason. I went aboard before breakfast and was enthralled by what happened at the breakfast table. The ward room was within shouting distance of the conn and the Officer of the Deck was giving positions to the skipper as we dove into the Puerto Rican trench out of San Juan harbor. As we approached the operating area, the officers were not enjoying the pleasantries of idle conversation over a cup of coffee, they were planning the attack. It didn't even feel like we were underway as there were no lurches and tilts as we maneuvered. They informed me that it was more like flying than sailing and most turns were with positive g's. The OD gave out the range and distance as we closed in. The captain assumed the conn and got down to the business at hand. It seemed like only minutes when the captain announced he had executed a successful attack and left some noise makers which the destroyer was pounding with depth charges (training type). He confirmed his report by going to periscope depth and watching the shenanigans of his opponent. Scratch the USS Abbott [DD-629]. That was the subject of many briefings about the skill and cunning our enemy, the submareener (not submariner) the ASW officer (me), gave out to keep the lads focused.

We were aroused at 0-dark thirty and marched smartly to the weather briefing for the trip home (smartly means the same direction). "Stormy," the aerographer, said we were in for a great day, puffy CU over the route back with a chance of thunder-bumpers at home. No sweat, we could land blind in Albemarle sound at 80 knots and 200 FPM down after departing Elizabeth city's ADF at 300 feet if Norfolk was socked in. Eight planes (two went to Bermuda the day before) motored about, trying to stay clear of each other, in the harbor preparing to take off. This is one of the draw backs of seaplanes; you keep moving while turning up the engines and getting into position for take off. This times 8 was stressful to say the least. We had the good fortune to be classed as power boats until we became airborne and then the rules changed in the twinkling of the eye. That day we were 3rd or 4th in line to depart. With a roar of our two 3350's, we launched off gracefully and attained the airborne state. The quality of the maneuver in retelling was directly dependant on whether you were at the controls or not. At about 300 feet we were greeted with the sweet aroma of rum being produced as we went through the smoke plume over the rum plant at the harbor's edge. This experience holds a special place in my memories of Spring-Board '60.

Stormy was right, it was a fair weather day but he hadn't told us about the sunrise we were to enjoy. The clouds had that bright aura around their edges and the sun's rays were streaming down to the sea below - it was very calm - sea state 0. Rod Hall, the navigator, gave us our heading home and the radio hummed with the "OUT" report to the skeleton crew at home waiting for us lucky dogs to return. We throttled back and were at our departure altitude of 8,000' and settled in for the trip home with "George," the auto-pilot, at the controls. On the VHF we could hear those in front and those who were falling in line behind for the trip. We were relaxed and the coffee was brewing. We were plotting right down the track and ticking off our progress with reports to base when Oceanic Control interrupted the serenity of a great day with a request to go to 9,000' for the remainder of the flight. In compliance with the order, we advanced the RPM and manifold pressure and climbed to 9K. Again we settled into our routine which was soon to be interrupted.

As we throttled back there was a huge explosion in the starboard engine. Since I was in the left seat, I couldn't see the engine so I requested a report on what could be seen visually; the instruments indicated we had a real problem. We started feathering number 2 and going to single engine operation. My thoughts of '”here is the closest sea drome, and could we make it back to San Juan” were interrupted with a message that would make these thoughts irrelevant. "Pilot, the starboard engine is on fire!" came from the afterstation and was confirmed by the copilot. Okay, let's just pop the fire bottles and settle that problem. The copilot took care of this as I concentrated on getting the single engine procedure completed. I was jolted out of my complacency with "Sir, it's still burning" from more than one station. My mouth was dry as I shifted to high frequency and screamed "MAYDAY! MAYDAY! We have an uncontrollable engine fire in our starboard engine!" I just knew somebody would hear my call on HF since once I had held a conversation with Manila tower while taxiing in the harbor at Norfolk. Next thought "That engine can burn the wing off; we got to get these guys out of here." I don't know how many times we hollered "MAYDAY" but quite a few I would guess. I told the copilot I would make a left spiral down to about 1000 feet; have the crew throw out the liferafts then we will all bailout; trying to stay together in a circle. I would be last out and I still didn't have my chest chute attached yet. For some reason that hadn't .gotten on my 'to do' list yet.

Upon reflection, I think I figured that we had to get the men out before the wing burned off, but if it did I couldn't possibly get out anyhow. The crew had proceeded to the afterstation and were ready to bailout on my orders. I was thinking that there are sharks down there; I hope we can get everybody in the rafts before they get to us. "The fire is going out" a voice on the intercom said. I thought--It's still flying, maybe we can get it down. "All hands to ditching stations we are going to take her in," I shouted into the mike. No response. I tried again. Still nothing. I looked down and the radio was still on HF (High frequency) and now the world knew what I was doing but they couldn't hear me in the afterstation. I shifted to intercom and the cockpit and flight deck was alive with the crew buckling up. I don't remember what the altitude was but Bob Deland, the copilot, went through the check list and asked for the flap setting. As I recall I hadn't given it a thought and told him "half flaps." Reality had set in and all we had to do was land in the open sea. This I wasn't trained to do.

See these aren't really seaplanes they are bay planes. I had endured an open-sea landing one time only from the nav table in PBMs in Korea when we were delivering a South Korean spy to the North Korean coast. [Note: On that one, wind WAS a big factor AND it was at night, … yer ole editor was the copilot … the takeoff was worse than the landing.] The sea was calm and it looked like a big bay with wide-apart speed-bumps (swells). Wind wasn't a factor; all we had to do was pick a heading and keep it on the water after touch-down. Yoke forward to keep from skipping off, back to keep from digging in. In a moment it was over and we were once again a power boat. At this point, I reasoned that, my selection of seaplanes at Corpus Christi had served me well. The flight engineer, "Snake" Snively, got out on the starboard wing with a fire bottle to check the damage. His report was good, the sea spray on the landing had put out any fire that had remained. The crew reported in and all was well and no one was hurt. We were in one piece. As the adrenaline wore off, it seemed like yesterday that we had an engine fire. Time had seemed to go into slow motion and for some reason time wasn't part of the equation while we tussled with the emergency. There had been plenty of time to do what had to be done and some time left over for thinking. It was kind of eerie and surreal. I mentioned this to someone later and I was told that he had heard something like this before.

Bob Deland took over and I hopped out of the left seat to see, for the first time, the damage to the starboard engine. The wing was scorched and the engine appeared to droop due to the heat and landing but other than that we were in business.

More strange happenings were about to occur when I tried to find out who had said "The fire was going out," nobody owned up. I was sure they misunderstood so I tried again with the same result; nobody knew. Since the initial shock hadn't completely worn off, it was easy to move on but this still haunts me to the present day. Guardian angels are real and present. We were about to settle into a routine for the third time that day. A quick check told us we were about to be a surface craft for a while, quite a while, as a matter of fact. We tried the hydro-flaps. A newfangled device consisting of two appendages under the aft hull which were extended by pressing down on the rudder pedals. They gave us directional control on the water and did away with sea anchors we had used in PBM's. Glen L. Martin thinks of everything with all the comforts of home. They also did not slow us down.

More strange happenings were about to occur when I tried to find out who had said "The fire was going out," nobody owned up. I was sure they misunderstood so I tried again with the same result; nobody knew. Since the initial shock hadn't completely worn off, it was easy to move on but this still haunts me to the present day. Guardian angels are real and present. We were about to settle into a routine for the third time that day. A quick check told us we were about to be a surface craft for a while, quite a while, as a matter of fact. We tried the hydro-flaps. A newfangled device consisting of two appendages under the aft hull which were extended by pressing down on the rudder pedals. They gave us directional control on the water and did away with sea anchors we had used in PBM's. Glen L. Martin thinks of everything with all the comforts of home. They also did not slow us down.

We were on our way to wherever, cruising on our good engine. I asked Rod, the navigator, for a course back to San Juan. The quizzical look on his face would stay with me the rest of my life. I explained we didn't have a great deal to do now and I thought we could close the distance for anybody that might come looking for us. He grabbed his trusty protractor and gave us a heading. We set course and settled in for the long ride back. It wasn't long before Erne Wilson, the Squadron XO, was flying over head asking if every thing was okay. He had heard our "MAYDAY" and had turned back to help. We reported "All's well" and advised we were underway back to San Juan. Shortly, a Coast Guard Search and Rescue amphibian, an HU-16 Albatross, joined the group and asked to be updated on the situation. The XO said he was going to head back before his fuel became critical and wished us good sailing. SAR passed us the word that we were to make for Grand Turk Island and meet the tender, USS Albemarle [AV-5], there as they were underway to us as we spoke. Rod broke out the charts to get us a course for Grand Turk. As we chugged along, SAR gave us a plot of our position and remarked, "do you guys know that you are making about 11 knots". This was the first time we were able to ascertain our speed because our navigation gear, Loran, didn't work unless we were airborne. About this time we were contacted by the USS Abbott (the same DD which the Nuke boat had 'sunk' in that exercise duel of skills). They informed us that they were proceeding at full speed to our location and would be there ASAP. We answered back we were steaming away from them at 11 knots and it might be longer than they thought before rendevous. In a few hours the SAR said he was going to Grand Turk as he was low on fuel. We asked him to fly over us on a course to Grand Turk so we could set our course. He complied with our request then departed. We were on our own until the USS Abbott arrived.

It was about dusk before we saw the masthead lights of the Abbott on the horizon behind us. It was after dark before she came abeam of us. They wanted to tow us. This was one of the exercises they performed for the ORl's (Operational Readiness Inspection). This didn't seem such a good idea as a following sea might put us into the fantail and we would probably sink. Also they would have to slow to steerage way and make for a slow transit. We declined the offer and requested that they take a position about 1000 yds or so on our Starboard beam and give us fixes about every 30 minutes in case we became separated. They agreed and we settled in for the night. It wasn't all that bad as it was 'full moon' time of month; when the sun went down, the moon came up. At first I hadn't thought much about it but we were soon to appreciate our good fortune. It was still sea state ‘0’ with a light breeze a perfect night for Caribbean cruising. That's what we painted later on the side of LM 8, (The plane ID number and our call sign was "8 Pelican" when she got home it was "Caribbean Cruiser".)

The moon went down, the sun came up and we prepared for our arrival at Grand Turk. The Abbott wanted to know our intentions and we replied we would anchor and would need less than 5 fathoms to give our anchor proper scope to hold. They said the position we had indicated was perfect. We had chosen this spot on our aircraft charts because the color was light blue; the destroyer must have assumed that we had surface charts. We chuckled at their presuming we had knowledge of seamanship and surface navigation. But before we could demonstrate our new-found abilities, the tender, USS Albemarle, arrived and took charge. They announced they would change the Starboard engine while we were at the buoy and we would be on our way. This was because they would not be able to be take us aboard the fantail for repair due to the fact they had just been configured for the new jet seaplane--the P6M--which required a ramp be cut in the aft area of the ship to allow the P6M to taxi it's nose in to work on the engines. (I imagine most people don't know the Navy had about 12 of these babies in the Martin Plant in Baltimore, Maryland that were scrapped before they got to the fleet. Our crew had the opportunity to see these planes as they decommissioned them.)

We taxied in close and told them about our observation of the damage to the mounts due to high temperatures during the fire. They raked us with binoculars and concurred with our observations which they would check when we tied up to the buoy they had laid in the harbor.

After tying up, we were welcomed on board the tender and informed we would probably be taxiing to GlTMO (Guantanamo Bay, Cuba) if they couldn't help us. They offered to replace the crew for the trip. This kind offer was refused as the crew voted, to a man, to see this thing through to the end. Besides we were having a ball regardless of the inconveniences and close quarters. We had 4 extra people who were just riding back, three from the squadron Maintenance department and a Lt. Smale from the Canadian ASW group; they wanted to stay on board too. Our requests for a fill up on gas to give us added weight was honored and we were about to have another startling discovery about our adventure.

On fueling, the gas had streamed out of the tank. At first 'we thought a valve had been left open but inspection revealed the main line to the starboard inboard wing tank had burned through. The squadron had a running argument about how to manage the fuel in the wing tanks and I had decided not to bum the inboard tanks until last. This would mean if we had burned these inboard tanks first they would have been half empty and when the manifold burned through the tank would have been a bomb and blown off the right wing dooming all aboard. Our guardian angel was doing a good job on this one too. The fire we would learn was caused by a blown jug (cylinder) and had been fed by the sloshing out of the fuel in the tank and it seemed that when the overflow was exhausted the fire had subsided and that kept our wing intact.

On fueling, the gas had streamed out of the tank. At first 'we thought a valve had been left open but inspection revealed the main line to the starboard inboard wing tank had burned through. The squadron had a running argument about how to manage the fuel in the wing tanks and I had decided not to bum the inboard tanks until last. This would mean if we had burned these inboard tanks first they would have been half empty and when the manifold burned through the tank would have been a bomb and blown off the right wing dooming all aboard. Our guardian angel was doing a good job on this one too. The fire we would learn was caused by a blown jug (cylinder) and had been fed by the sloshing out of the fuel in the tank and it seemed that when the overflow was exhausted the fire had subsided and that kept our wing intact.

Gas wasn't the only thing we had ordered. Steaks and ice-cream seem to have mysteriously appeared on the list of "had to have" items for the yacht trip to Cuba. We did have a galley to cook the steaks but we were not blessed with a freezer for the ice-cream. Hope springs eternal in the breasts of flight crews it seems. As we loaded our supplies someone dropped a bottle of catsup on the steel deck splattering the ship's Executive Officer who was looking after us with what looked like blood on his immaculate white summer uniform. He graciously excused himself and returned in a fresh set of whites looking none the worse for the experience.

It was late in the evening and time to get underway for the trip to GITMO. We cast off and were provided with a crash boat from the tender to lead us through the coral heads which were visible only because of the white breaking water over them. The 'devil' was not to let us off that easily however. The USS Albemarle came up on our frequency with the notification that she was returning to port with a medical emergency which could be handled only at Grand Turk. (an emergency appendectomy). The boatswain commanding the crash boat asked of our intentions. We replied that we were all secure and he had better return to the ship before daylight disappeared and made his transit through the coral heads more difficult. We were now on our own, having departed of our own free will not due to an emergency. This was to be my first and only command at sea. I guess I could have paced the flight deck with my hands clasped behind me like Charles Lawton in ‘Mutiny on the Bounty’ or perhaps rolled my steel balls like Captain Queeg but it just didn't seem right. "Damn the coral heads, full speed ahead" was the order of the day. We were just passing the last coral head as the crash boat broke off and headed back.

For some reason we were being served huge servings of soft ice-cream dessert before the evening fare of steak on the cruise ship we were embarked on. Seconds were in order as five gallons had to be consumed promptly before it melted. We set the RPM at 1500 and the hydro flaps 'thumped' as we made our way into the open sea. Free at last! We were quickly falling in to the routine that would last for the next 24 hours. We had it made, reclining chairs on the flight deck, stove in the galley and four bunks aft with a breeze wafting through the afterstation hatches. The ice-cream was gone and we were consuming our steaks as if they wouldn't last through the night, and they wouldn't for the same reason as the ice-cream. Everybody stood a watch as needed. The pilots steering the craft, the flight engineer watching the engine, the radioman with position reports and others keeping watch. I reminded the crew, that there would be no sun bathing on the wings. We didn't need sun bum or having to fish someone out of shark infested waters. Later that night the Tender pulled along side to give us mental comfort and position fixes on our progress. The moonlight on the water was impressive and had some of us wishing our ladies were along for the ride. After all it was February 14, St. Valentines day.

Dawn came up like thunder, as the song goes, and ham and eggs and coffee were served to celebrate the beginning of the new day. The hydroflaps thumped first on one side then the other. We could not hold them in a half open position and had to fully extend one at a time. As a result of this continual pounding we had a small mishap. During the night one of the crew received a nasty bum when he rolled over in a bunk and touched a red hot hydraulic line. After breakfast the ship contacted us by radio and told us that the "Padre" had hooked up the VHF to transmit the church service to us. The memorable part of the service was the crew singing the hymn "Almighty Father, Strong to Save" (the Navy hymn). The verse that says "For those in peril on the sea" hit home that day and my mind wandered to the voice I had heard during the fire. This rendition with all male voices was stirring and prompted our flight engineer "Snake" Snively to remark "We Needed That." We were making good progress and were closer in to the Cuban mainland than the ship because they had to have deeper waters. About dusk we were just off GITMO when the ship informed us we were to enter the port unassisted. Wow! I hadn't even thought of this but it was reasonable if not mandatory. After all we both couldn't fit into the entrance. The moon had come up on schedule and made it brighter but it was still plenty dark especially to the Patrol Plane Commander who was 'shooting' the channel--ME! We didn't have any instruments for this sort of work so we just used our hands to indicate the angle to the marker and our desired bearing. Then we would pop back into the cockpit and compare with the compass. It was up and down then hit the hydro-flaps and do it all over again. I have often mused about this comical scene with us popping up and down like a jack-in-the-box in the cockpit of this semihelpless P5M. We made it in only to find the bay filled with aircraft carriers. Lights were everywhere and we retreated back out of the bay. We then saw the lighted ramp off to the port and made a hasty approach to the buoy. Searchlights were illuminating the ramp area and we slowed by blipping the one engine (switching the mags 'on' and 'off') and using the hydro-flaps for what they were designed for. We 'made' the ramp buoy and our beaching gear was being delivered by the rearming boats with their padded gunwales. Since we were not amphibious, we required wheels with flotation tanks to be clamped on and pulled up a cement ramp by a tractor to be accommodated in the parking area. As we were hauled up we heard what we first thought to be cheering but much to our disappointment it was only the crowd at the outdoor movie angrily calling for the ramp lights to be put out so they could see the movie. Another reality check. Our radio operator tapped out the "IN" report to home base indicating mission completed. We loaded our gear in the bus and retired to our quarters for some needed rest.

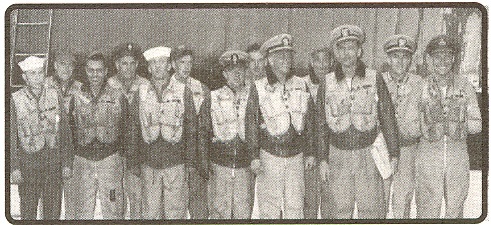

In a few days the squadron sent a plane to GITMO to retrieve the "wayward ones." The maintenance officer was upset because I had given some secret electronic equipment to the Tender for safe keeping and they were long gone on another mission. We returned home to a welcome prepared for us by the PAO (Public Affairs Officer) officer.

We were heroes and had been the subject of the TV nightly news while we were gone. My folks had heard the news on our mishap via one of these broadcasts. We were interviewed by the local paper and when asked for an outstanding remembrance, all I could think of was the expression on the navigator's face when I asked for a course to San Juan. I guess we answered many more questions because the article next day had a more complete story. It could have been that the PAO had a good press release for the occasion. We lined up for pictures for posterity, adorned in our sweaty flight suits and the accompanying aroma from our cruise. There were rumors that our 55 hour and 550 mile voyage had set some sort of a record but it wasn't verified. I did learn that one of the planes on the first transatlantic flight had taxied 55 hours to the Azores. I've been told that is part of an exhibit in the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola. Our adventure was history and it was now back to work for the returning heroes.

Later an encounter with CDR Peoples, our personnel officer, and the leader of the two plane detachment to Bermuda, left me wondering. He told me that at 0800 on the morning of the fire, he had been awakened with a dream of one of the squadron planes with an engine fire crashing and cartwheeling on landing. Cartwheeling was what we called it when a seaplane would dig in one of the wing floats into the water while landing and the results of such a maneuver. I have never known of such a crash except in films. Curious I questioned all of those in the landing if they had such a fear. Only Rod Hall the navigator said he was really sweating the open sea landing and had imagined cartwheeling. This was ESP. I had been involved in some similar experiments with Dr. Rhine, while I was at Duke university, in this vein and had heard of people as far away as London transmit data with better than the probabilities predicted for chance. You will probably understand when I say I was most careful what I thought and said around Rod after that.

It was years later when I saw a TV documentary on the legendary Devil's Triangle (The Bermuda Triangle) that it dawned on me that we had landed in about the middle of a triangle with boundaries between the points of Bermuda, Miami and San Juan, and some show it even as far north as Norfolk. We had operated in this area as a matter of course without realizing that we were stepping in the Devil's own territory. My wife likes to remind the listeners of the story that I am a "Bermuda Triangle reject." I hasten to remind her that we were not thrown out, it was just that the Devil blinked and we sailed out the back door.

A final note. When I told this story one time to a sailor who had sailed through the windward passage, he said he had never seen the waters there when it wasn't rough and windy. I don't care what they say about the Bermuda Triangle, that's a place where the unexplained is the norm and it's good to be on the alert.

Here’s hoping for a fair wind and a following sea for us all that are left.

|

Crew: |

|

Passengers: |

|

Plane Commander |

LT Ray W. Myers |

G.L. Shugarts, AMC |

|

Copilot |

LT Robert E. Deland |

K.C. Morris, AMC |

|

Navigator |

LTjg Rod D. Hald |

D.E. Lettner, AMS2 |

|

Observer |

Flt LT H. Smale, RCAF |

T.D. Brown, ADR3 |

|

Plane Captain |

E. Snively, AD1 |

|

|

Electronics |

Harry E. Steel, AE1 |

|

|

ECM Operator |

J.W. Gibson, AEMAN |

|

|

Ordnance |

R.M. Chamberlain, AO3 |

|

|

Radioman |

J.J. Wojton, AE3 |

|

NAVY PILOT BEATS WORLD RECORD

FOR WATER TAXI

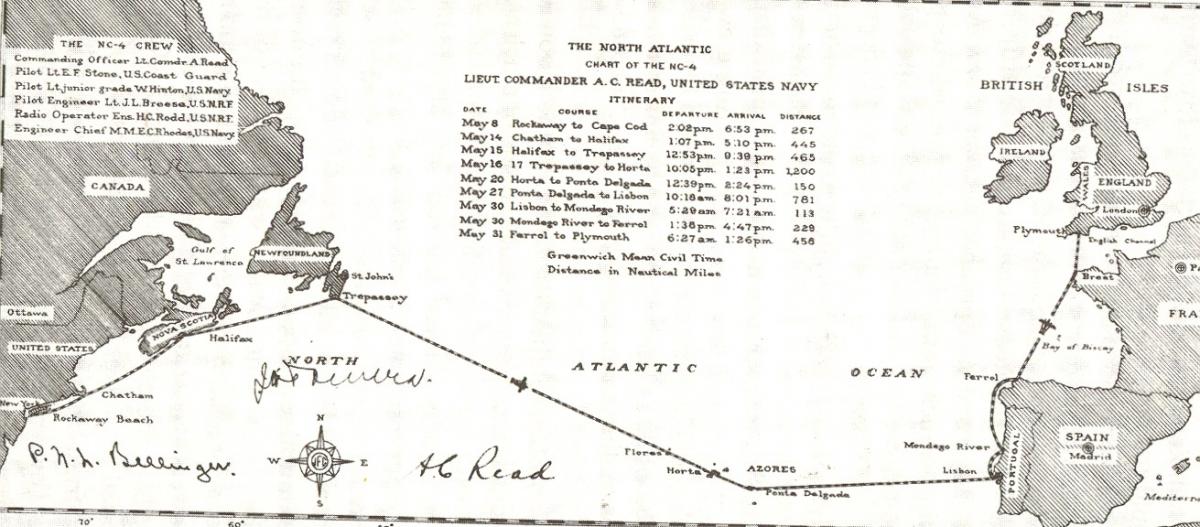

In February 1960, LCDR Ray Myers, USN, (former Flying Midshipman) eclipsed CDR John H, Towers’ record of 53 hours and 205 (nautical) miles hours set in May 1919 water taxiing the NC-3 following an attempt to fly across the Atlantic non-stop (the NC-4 succeeded in this attempt).

LCDR Myers’ journey of 55 hours and 550 miles, was made in a Martin P5M from VP-44 following an attempt to fly from Puerto Rico to NAS Norfolk, Virginia.1

CDR Towers’ excursion was from off Newfoundland to the Azores. 2 LCDR Myers’ journey was from 34½ miles south of Horta to Ponta Delgado (both in the Portuguese Azores, following a precautionary hard open-sea landing.

A later attempt to break this record was made in 1959 by LCDR James S, “Steve” Christensen and his crew flying (or taxiing) a Martin P5M-2 from VP-45 from NAS Jacksonville, FL, and return to Mayport, FL.3 His try of 26 hours and 200 miles, failed to break Towers’ record.4

Mantz’ narrative:

1 See Ray Mantz, ________, Flying Midshipman Association, The LOG, ______; Association of Naval Aviation, Wings of Gold, Spring 2013, .

2 See ___________________________________________.

3 See CAPT Richard K. Knott, Wings of Gold, Spring 2013.

4 See CAPT Knott, The American Flying Boat – An Illustrated History, U.S. Naval Institute.

“The Day the Devil Blinked”

A Pennsylvania native, from Philadelphia, author Myers was drafted by the Navy in September 1945. After boot camp he joined the V5 program, attended Duke University under the Flying Midshipman program, entered flight training in 1948, and after earning his wings, served in VP-42 in the Korean War, earning three Air Medals. He was a flight instructor in SNJs and served on the training carrier, USS Saipan, before completing studies at Duke University, earning a BA in history. He served in VP-44, and had assignments in NATSF Philadelphia, and COMFLEETACTS Ryukus, Okinawa. He was in the Navy Schools Command in Pensacola when he retired in 1970. His first wife passed away in 1983 (three children) and he currently lives in Cantonment, Florida with wife, Mary. They have four children. He’s a Lifetime member of ANA, and belongs to the Flying Midshipman Association, the Retired Officers Association, and serves on the board of the Waterfront Rescue Mission, Pensacola, Florida.