BRIEF BIO

My Navy life was based on the premise that if you can remain “well-rounded” you can go through life without any direction at all. I served in VT (training),VS (anti-submarine), VP (patrol), VR (transport), and VQ (recon-naissance) squadrons -- thus never having the “required warfare specialty” the Navy desired.

I also wandered about the academic environment our Navy operates, becoming the most Navy-educated (therefore probably untrainable from the Navy’s viewpoint) officer ever in Midshipman annals. I graduated from the Navy Line School, Naval Justice School, Defense Public Information Officer’s School, Navy Postgraduate School, Naval Command and Staff Course (Newport), Naval Warfare College (again Newport) and the National War College in Washington, D.C.

My sea excursions included Air Operations, USS Badoeng Strait, Navigator, USS Boxer, and Operations Officer, USS Okinawa. I was qualified, thusly, as an Officer of the Deck on three different types of ships, once again maintaining my ability to become a specialist in nothing nautical.

To complete my chaotic career, I served in the Bureau of Naval Personnel, the Office of Naval Operation (OP-61). Deputy of the Human Goals Program, Deputy to the Chief of Information, Professor of Naval Science (Nebraska University), and Senior Naval Research Writer at the National Defense University. (Note my ability to continue avoiding any “duplicate duties” that might have provided me with any expertise in a given field).

My scribblings include two published books and numerous articles in varied (naturally) publications on diverse (as might be suspected) subjects. My lifelong goal is to settle on something professional, as other human beings seem to do. Perhaps either tree or brain surgery would entice me, but then I would most likely lose interest after a time. It’s so hard to gain direction, don’t you think?

“The Navy’s Flying Midshipmen”

THE HOOK, summer 1987. pp 16-20.

by CAPT Walter “R” Thomas, USN (Ret)

“To friends with wings forever folded; their fortune was not so good as mine.” Ernest K. Gann

Forty years ago, surely inspired by those Naval Aviators who survived the massive ocean operations of World War II, some 3,600 young men signed contracts to become a unique group known as “Holloway’s Hooligans”. Some of them became the only U.S. Navy flyers to enter combat as midshipmen. Their story begins in 1946, when Congress approved the Holloway Plan, perhaps the most innovative and productive reorganization in the history of Naval Aviation training.

As the veterans of WW II returned to civilian life in 1946, the corps of experienced Naval Aviators was thinned considerably. To confront this personnel problem, VADM James L. Holloway Jr. (“Gentleman Jim”) devised a plan to recruit high school graduates – as well as flight cadets already in training who were to be released from duty – into a new program. It proved successful; in the next four years, of 3,600 candidates who entered the Aviation Midshipman syllabus, about 58 percent earned their Wings of Gold.

The first class started in the fall of 1946, composed of former cadets who were well into the flight training program and chose to be redesignated Aviation Midshipmen rather than be released from active duty. The last Pre-Flight class was in 1950 when the program was terminated in favor of accepting college graduates, mainly from the Naval Academy and Naval ROTC courses, as aviation candidates.

The main difference between the midshipman program and other aviation training schemes was that the Midshipmen were commissioned Regular Navy whereas Aviation Cadet (AvCads) were always Naval Reserve. However, Mid-shipmen were not commissioned when they received their wings, but two years from the date of warrant when they entered Pre-Flight. Thus, they were scattered over the earth in squadrons for periods varying from four to fourteen months as “Flying Midshipmen” with BOQ / shipboard mess bills they could not afford to pay, uniform requirements they could not possibly purchase and TAD assignments that incurred even greater debts for their meager means of $112.50 to $132.50 per month.

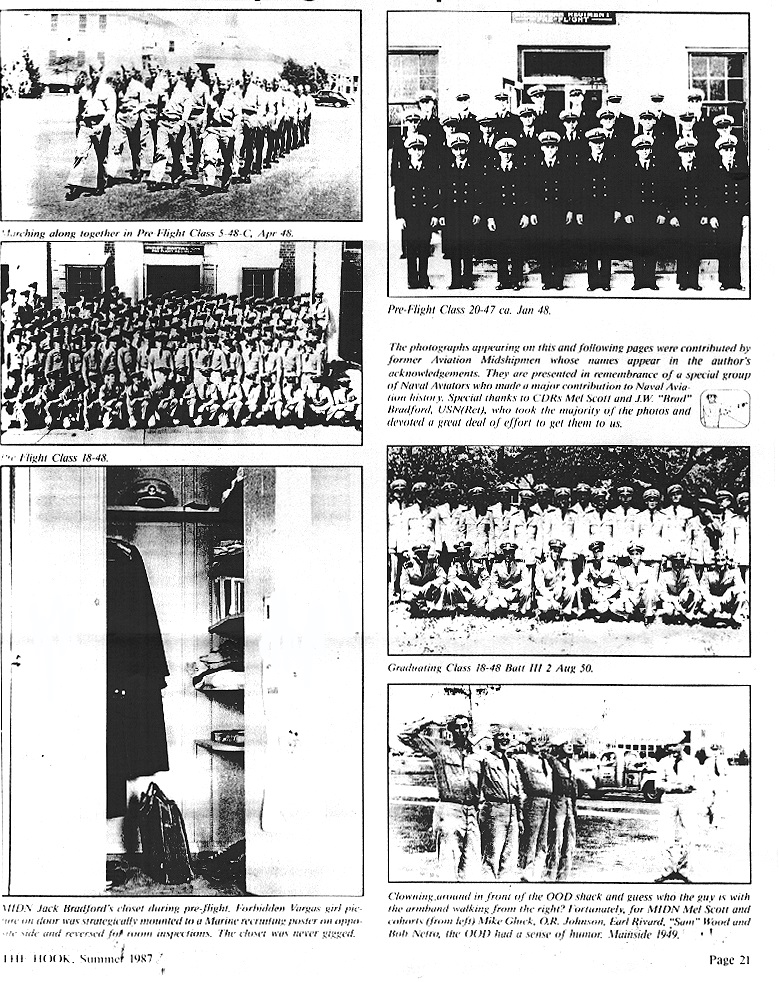

But all that was in the future when the aspirants signed on. The attraction for 1946 high school seniors included a two-year guarantee of full tuition and book costs and subsistence payments of $50 per month while attending college as Airman Apprentice. After completing two years of an engineering or science curriculum, the future aviators were sent to Pensacola – still as Airmen Apprentices. On arrival they were ordered into a four-week period of humiliation training in an Officer Candidate Training Unit (OCTU) where they marched, mustered and matriculated under the ever-present critical eyes of chief petty officer instructors. It was not a pleasant interlude.

When all physical examinations and OCTU training requirements were successfully completed, the new candidates were issued khakis to replace their dungarees, and passed into Pre-Flight. Once knighted there as Aviation Midship-men, the still-confused students encountered impeccably-uniformed Marine Corps sergeants who assumed the gentle duties of daily drills, frequent inspections, and an even more orderly life than the CPOs had imposed in OCTU. Now church attendance was mandatory, liberty nonexistent and physical training almost abusive. Pre-Flight was, if possible, less joyous than OCTU.

By September 1948 Pensacola was understaffed, heavily burdened and mostly overwhelmed by the mass of students who descended on Training Command from their two years of college. Logistics collapsed, food was short and uniform sizes subject to availability and each supply clerk’s disposition. Many Reserve officers were ordered in to help coordinate the chaos.

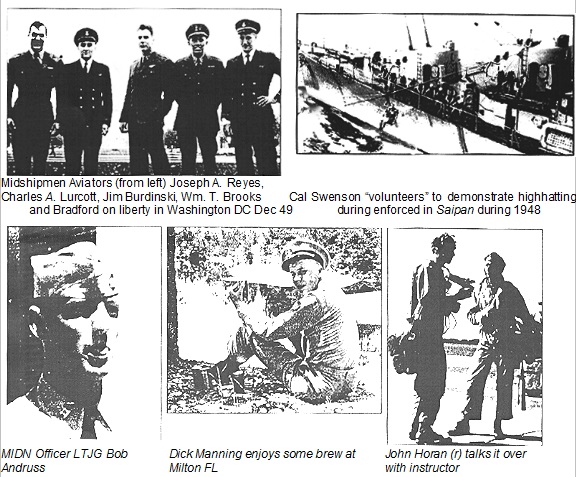

As the early summer arrivals completed Pre-Flight and crowded the Basic flight training classes at Whiting Field, a “back-up” occurred at Mainside. The late summer students who finished Pre-Flight in November and December could not be accommodated at Whiting. Never at a loss for solutions, the Navy sent these latter groups on board USS Wright (CVL-49) for intensive training in deck chipping, red lead painting and watch-standing. CAPT C. A. L. “Cal” Swanson, USN (Ret) was one of those unfortunate souls. The emphasis was on “standing”, as Cal recalls, “There was no place to sit down on that ship!” These “student pools” were long stagnant, and life was not improving.

However, the rigors of the Midshipman program served a useful purpose. Cal Swanson (Class 20-47) recalls the cohesive effect of those days. “The spaghetti feeds, the beach parties, the same group of girlfriends, really developed a bonding of the Midshipmen. Those who remained with the program through CQ and into fleet squadrons seem to have a special relationship.”

As in other hierarchies, the Aviation Midshipmen were forced into a pecking order. Fourth Class Midshipmen included all those in Pre-Flight; Third Class were in Basic at Whiting Field; and Second Class were either at Corry Field (instruments and night flying) or Saufley Field (formation and gunnery). The differences in status were negligible and almost invisible, consisting merely of locating collar anchors here or there. Hard liqueur, cars and marriage were strictly forbidden.

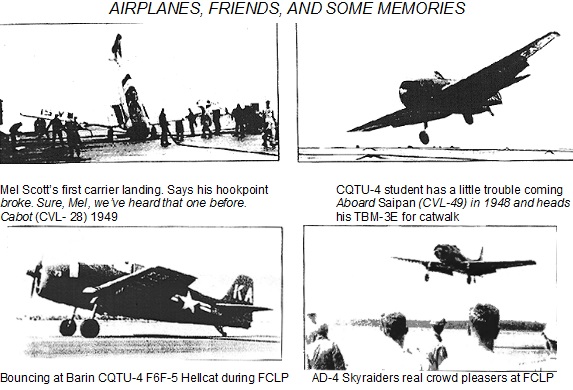

Eventually, after 10 to 12 months, Basic training ended. The culmination of Pensacola penance was Field Carrier Landing Practice (FLCP) at Barin Field (“Bloody Barin”), followed by CarQuals on either Wright or Cabot (CVA-28). Qualifying aboard was the true and blessed passage into “Midshipmanhood.”

Once carrier landings were completed, the fledgling became a First Class Midshipman, a rank considered equivalent to Arabian prince. This title permitted the student, for the first time, to wear aviator greens, brown shoes (half-Wellingtons preferred), an anchor on each collar and a half stripe on his uniform sleeve. Most importantly, liberty was now unrestricted and hard liquor – even for those who hated it – could be consumed, preferably in the company of those lesser-ranked Midshipmen gathered around each CarQualled hero.

In every way Pensacola life was balmy for those First Class Midshipmen who spent their last few basic training days in the bar of the San Carlos Hotel, or were semi-permanent denizens of the AMVETS Movie Theatre.

The prestige quickly ended as the new Middies left Pensacola for advanced training at Corpus Christi, Texas, and outlying fields. One episode at Cabaniss Field during F6F phase in 1949 involved an extremely religious individual who was not the best aviator of his class, and an ex-Catholic who flew like a swallow. In the briefing room awaiting a hop the devout flier was seen praying on his knees. Irreverently, his classmate said, “If you gotta’ pray, then pray for me. I gotta’ fly your wing today!.”

Thus, in single and multi-engined aircraft, the final stages of flight training soon were completed and each Midshipman received his coveted Wings of Gold.

Why weren’t these aviators commissioned as ensigns? Because, in all innocence, their initial “warrants” as Aviation Midshipmen specified they would be commissioned two years after their date of rank, and many completed flight training in 15 to 18 months, some even less if they had been cadets in 1946. CAPT Bill Stuyvesant, USN (Ret), who many claim to be the shortest aviator in history, received his warrant in December 1946 and was designated a Naval Aviator in February 1947. Commissioned in February 1948, Bill was given a date of rank as of June that year – almost 18 months after he joined his fleet squadron.

In June 1949 all Aviation Midshipmen in Basic, at Pensacola, and in Advanced, at Corpus and environs, were sent home on 30 days leave because the Navy ran out of money for aviation fuel. Remember, these were the days of SecDef Louis Johnson, no friend of the Navy and Marine Corps.

Some of those designated aviators before the Korean War were released from active duty and encouraged to join the Naval Reserve. The Regular Navy, it seems, did not want to increase the number of officers between 1948 and 1950 on financial grounds. Quite expensive, don’t you know.

Former Midshipman CDR Bob Bennett, USN (Ret) recalls a succession of invitations to get out of the Navy. As the program evolved through 1948 and 1949, at each stage the first option always was leaving the service. “We imagined two big guys with a pitchfork standing by to toss us out,” Bob says. But most of the aspiring aviators stuck with it.

Then the shoe fell. On 19 may 1950 BuPers announced that fewer than 40 of the 450 or so middies from the Class of ‘49 had been selected for retention. The others were to be released to inactive duty the last day of June.

When the Democratic people’s Republic of Korea invited itself southward 25 June, most U. S. Navy budgetary restraints disappeared overnight. The foresight of VADM Holloways’ plan became apparent, but not without a glitch or two. Three days later, 28 June, SecNav decided Aviation Midshipmen could remain until 31 July if they wished. This is noteworthy. Within two days of legally avoiding the new shooting match, only one Midshipman opted out. And that had less to do with avoiding combat in Korea than with avoiding matrimony in San Francisco. As for the others, one aviator spoke for many when he said, “We wanted to do what we’d been trained to do.”

The SecNav dispatch was amended 14 July when AirPac authorized retention for former Midshipmen for 12 months. That fall the “Forty Nines” were notified they could remain on active duty “indefinitely,” but no amendment to pay scale or seniority was forthcoming in the bargain.

Meanwhile. a former Flying Midshipman already had been killed by hostile action far from the new war zone. On 8 April 1950 a VP-26 PB4Y-2 from NAS Port Lyautey, Morocco, took off for a mission over the Western Baltic. Among the ten-man crew was 21-year-old Midshipman USN Tommy Lee Burgess, who had entered the Midshipman program in 1947 and was designated a Naval Aviator in June 1949.

When the Privateer was reported overdue, a search was initiated by VP-26 and USAF aircraft in the assigned patrol area. Eventually debris was recovered which proved that the bird had gone down in international waters. The Soviets claimed it had been mistaken for a B-29 over Latvia, where it allegedly fired upon intercepting aircraft. The Russian version clearly was a lie, but no trace of the crew was found.

The first former Aviation Midshipmen to fly combat over Korea were two Air Group Five pilots, Ensigns Gordon Strickland of VF-54 and Jerry Covington of VA-55, who launched from Valley Forge (CV-45) in July 1950. When Leyte (CV-32) arrived on the line in October she brought a batch of ex-middies in CVG-3. There were half a dozen in VF-32 alone, including ENS Jesse Brown, one of the most popular pilots in the air group. He died in his crashed Corsair 4 December [1950], despite the Medal of Honor effort to save him by LTjg Tom Hudner. It so happened that Jesse Brown was black, the first Naval Aviator of his race, but that was unimportant to those who knew him.

In his last letter to his wife, Brown stated, “Knowing that he’s helping the poor guys on the ground, I think every pilot here would fly until he dropped in his tracks.” It was a sentiment every carrier pilot seemed to share during the endless, chilling days around the Chosin Reservoir.

Nor was Jesse Brown the only Aviation Midshipman to set a precedent. Joe I. Agaki had become the first Niesi to win Wings of Gold and he, too, flew combat in Korea.

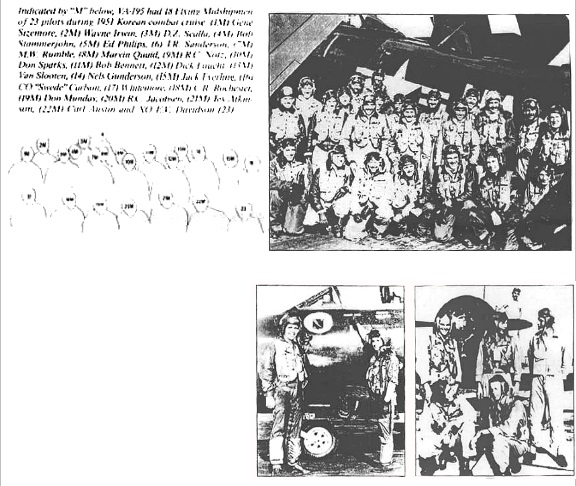

The influence of flying middies in some squadrons was astounding. Depending on timing and fleet needs, Midshipmen could be sent in large groups to some units, where they formed a decided majority. A case in point was VA-195 during 1951, which deployed with 18 former middies in a complement of 23 aviators. Interestingly, one of these pilots had received his “walking papers” in the May 1950 cutback. Reflecting the doubtful wisdom of BuPers, former Aviation Midshipman ENS Gene Sizemore continued his Navy career and achieved flag rank.

Despite their unquestioned contribution to the effort in Korea, most flying middies found that their original contracts dogged them for decades thereafter. To add insult to penury, two years of active duty as a Midshipman in training and as a squadron pilot did not count for longevity pay or retirement. This quirk in the law finally was resolved in 1974 when fewer than 100 former Midshipmen remained on active duty to benefit from the revision.

The 2,100 men who became Flying Midshipmen between 1946 and 1950 served their nation well – through Korea, the Berlin Airlift, Cuban Missile Crisis and Vietnam War. They were among the most dedicated and professional flyers in the Navy for three decades. The last Regular Navy Midshipman on active duty was RADM William Gureck, who retired in 1984, while RADM Les Smith and Buzz [Buz] Warfield remain on duty as Reserve officers.

The record would be incomplete without special recognition of former Aviation Midshipmen Howard Rutledge and Harry Jenkins who endured more than six years of horror and torture as POWs in Vietnam. They highlight the courage, sacrifice and valor of those Flying Midshipmen who served their nation so well in peace and in war.

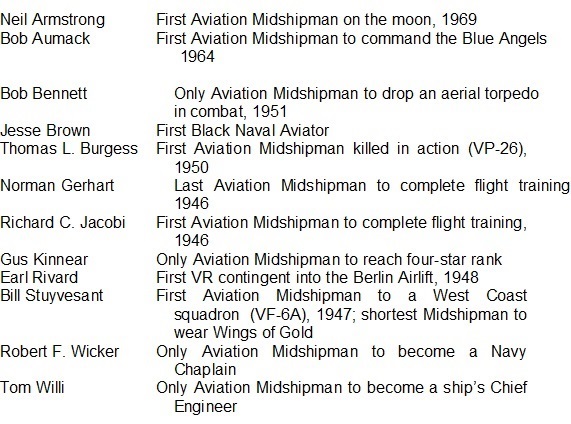

No records long remain unchallenged, but as far as the author can determine, the following are a few significant facts concerning Flying Midshipmen.

The Old Navy

“Holloway’s Hooligans”

By Captain Walter “R” Thomas, U. S. Navy (Retired)

The U.S. Naval Air Training Command in Pensacola, Florida, was the “Annapolis of the Air” – literally – from 1946 to 1950. In those four years, more than 2,000 “aviation midshipmen” earned their wings – but not their commissions – and became some of the best financial bargains in U. S. naval aviation history.

Toward the end of World War II, the Bureau of Naval Personnel realized that the Navy would soon face a fleet-wide shortage of officers, many of them naval aviators, when the mass exodus of combat veterans began. To keep the officer billets filled, immediate replacements in huge quantities would be needed. In response, a Navy board headed by Vice Admiral James L. Holloway, Jr., forwarded a plan that could procure sufficient numbers of trained officers to satisfy the needs of our greatly expanded postwar fleet.

The Holloway Plan, approved by Congress in August 1946, was probably the most successful large-scale reorganization of the U. S. Navy’s training structure in its entire history. Essentially, the plan “beefed up” the Navy’s recruit officer training program and offered new incentives to prospective candidates, including pay. It was the kind of facelift that the program needed in order to train larger numbers of career-oriented officer candidates.

The naval aviation community – anxious to get its officer candidates into the cockpit as soon as possible – was accommodated by Admiral Holloway in his plan, and “aviation midshipmen” were born. High school graduates were recruited into the Navy as airman apprentices, attended college for two years, then reported to Pensacola for about 12 months of flight training. While there, they were designated aviation midshipmen and later went on to earn their wings at advanced flight school at Corpus Christi, Texas. However, not until a full two years from the start of preflight school would these bureaucratic oddities (known as “Holloway’s Hooligan’s”) be commissioned as bona fide ensigns. But while they waited to become full-fledged naval officers, these “flying midshipmen” found themselves assigned to operational squadrons throughout the fleet, many of them flying combat missions in the skies over Korea.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

"Proceedings," April 1984 issue (pages 154-157)

Few now remember the once-active train station at Pensacola, and fewer still recall the lonely depot at Flomaton, Alabama; both terminals have long been abandoned. In the summer of 1948, Flomaton became the transfer point where the fast trains between New Orleans and Atlanta stopped briefly in the dark and at absurd times, usually between 0300 and 0400, to disgorge the future flyers. After waiting about two hours on this drab and dismal platform, a remnant of the railroad industry would stop to reembark the dazed and disoriented trainees on their final milk run to Pensacola.

Because aviation midshipmen were not allowed to own cars (nor could they afford them), and since the Navy only authorized rail transportation on a midshipman’s prepaid travel request, the “Flomaton Flyer” was the austere and only route to Pensacola for thousands of future aviators – it was a discouraging introduction. Subsequently, it is reported that no “flying midshipman” ever retired in Flomaton.

Between June and September 1948, five battalions of fledglings descended on and overwhelmed the training command’s capacity for housing, clothing issue, classroom instruction, and – especially – food services. The men of the Fifth Battalion, known as the “Famished Fifth,” because they were fed last, often were lined up in formation for 200 yards awaiting their turn to eat. Members of this distinguished group still recall those many mornings of cold cereal (but no milk), toast (but no butter or jam), and “We just ran out of meat and eggs.” Gluttony was not a sin in the Fifth Battalion – it was a fantasy. For the last six months of 1948, the candy bar machines throughout the base reaped unimagined profits and were usually empty by 1000 each morning. In addition, the “gedunk” sales records for the same period at Pensacola have never been broken. It was a hungry year.

Because of the massive influx of students in the summer of 1948, it was necessary for the new arrivals to “marinate” four to six week in an officer candidate training unit (OCTU) where they retained their rates as airman apprentices. In OCTU, the prospective aviation midshipmen were trained in the fundamentals of abuse, under the oppressive Florida sun and the reproach eyes of marine sergeants. Liberty was never permitted; drill, discipline, and obsessive cleanliness were taught more as commandments than as principles.

The OCTU students also received exceptionally thorough physical examinations, severe exercise schedules, and both routine and surprise room and personal inspections. Demerits were awarded liberally and extra duty rifle drills and marching hours were constant hazards. Those who survived OCTU were warranted as aviation midshipmen and ordered to pre-flight school. But the inspections and marine sergeants remained, thus giving birth to the lament, “Them that flunked was the lucky ones.”

The horde of students created a backlog throughout the flight training syllabus from 1948 to 1950. Many aviation midshipmen who completed pre-flight school late in 1948 had to wait for their initial flight training billets to become available at Whiting Field. This time was conveniently filled by assigning the students to temporary paint-chipping duties on board the Pensacola-based aircraft carrier USS Cabot (CVL-28). The stagnant flight training situation was further aggravated in June 1949, when everyone was sent home on leave for a month because the Navy ran out of money to buy aviation gasoline. Then the numbers of aviation midshipmen dwindled rapidly as the Defense Department made severe budget cuts in 1949. As a result, many of the earliest students (1946-47) earned their wings and discharges concurrently; it was a Kafkaesque world.

While the coveted title of “first class aviation midshipman” has no counterpart in the fleet today, it once was the epitome of social structure at the San Carlos Hotel in Pensacola. As a student progressed through basic flight training, he advanced through the fourth-, third-, second-, and first-class stages of “midshipmanship.” The first three stages were somewhat meaningless since the student merely switched his collar anchor around, continued to wear his khaki working uniform with black shoes, and had very little liberty. But on achieving first class aviation midshipman status, fundamental changes in appearance and confidence became apparent.

Unlike his junior counterparts, a first class aviation midshipman wore his anchors on both collars, sported brown shoes (usually half-Wellingtons), donned aviation greens, was permitted unrestricted liberty, and was allowed to drink hard liquor rather than only beer or wine. These Olympian privileges, reserved exclu-sively for those who were carrier-qualified and on their way to advanced training in Corpus Christi, were prestige symbols that have seldom been equaled in the annals of naval society. Nevertheless, even at Corpus Christi, the rite of marriage was still forbidden. Those who chose to live off base were quickly investigated for evidence of conjugal bliss.

By 1950, the unpleasantness in Korea had erupted, and the Defense Department reversed its practice of sending many aviation midshipmen home after they had earned their wings. Now the flight students were graduated and sent to operational billets.

One immediate problem with the arrival of this new crop of aviators in the fleet was their title of aviation midshipmen. This resulted from the contract that required them to remain as midshipmen for two years from their date of warrant, although they had completed flight training and joined the fleet. Often, the operational squadrons were undecided about where they should house such a distinguished brood; they weren’t enlisted men, and they weren’t officers. Money also was a complication, since the bachelor officers’ quarters with its closed mess charged a monthly rate for occupants, and aviation midshipmen were always broke. They only earned $132 a month, including flight pay and subsis-tence. Many still owed money for such necessities as their aviation greens, and few had any means of transportation. Fewer still had what creditors term “a reasonable means of support.”

Another economic facet of squadron life was that aviation midshipmen only received three cents a mile for travel to their duty stations, while ensigns received eight cents a mile. Matters were further complicated by the fact that “midshipmen” were only allowed to ship personal goods between their homes and Annapolis – and none of the aviation midshipmen were going to Annapolis.

A final blow for many was that they were given a date of rank as ensigns long after they had earned their wings. Aviation Midshipman William Stuyvesant, one of the earliest graduates, was warranted as an aviation midshipman in December 1946, designated a naval aviator in February 1947, commissioned as an ensign in February 1948, and given a date of rank of June 1948 – almost a year and a half after he joined his squadron. Life most certainly was not easy in the case of Holloway’s Hooligans.

Mr. Micawber (one of Charles Dickens’ favorite characters), when con-fronted by a legal contradiction, replied “If the law says that, sir, then the law is an ass.” It was soon discovered that the laws relating to “flying midshipmen” were quite often “asses.” The service time of aviation midshipmen could not be credited for longevity, pay purposes, or even as active duty time. For about a quarter century, despite the efforts of many distinguished congressmen and the multitude of personal letters written to the Navy and Defense Departments, all attempts to change the U. S. Code for aviation midshipmen were fruitless. Finally, in 1972, the subject was addressed favorably, and the law was changed to include aviation midshipmen with flight officers in the U.S. Code. Pay was adjusted for those still on active duty, but by 1972, few former aviation midshipmen qualified and no retroactive adjustments were authorized; less than 100 offices were affected by the “corrective” legislation.

As a result, in addition to recruiting the least expensive naval aviators in history at $132 a month (including flight pay), the government saved perhaps millions of dollars by not authorizing a two-year “fogey” for the aviation midshipmen who served on active duty for more than 20 years without credit for their “midshipman time.” At the first Pensacola reunion of the Flying Midshipmen in April 1982, one of Holloway’s Hooligans remarked, “We were cheap at half the price.” From another quarter came a more apt response: “We never even got half the price!”

Captain Thomas entered the Navy at Pensacola, Florida, in 1948 as one of the Navy’s “Flying Midshipmen.” While assigned to various squadrons, he flew many different types of aircraft, including seaplanes and helicopters. He also served tours as a ship’s company officer on several aircraft carriers. His shore assignments include duty as a flight instructor, Special Assistant to the Chief of Naval Personnel, the U.S. Naval War College staff, and the Politico-Military Policy Division of the Chief of Naval Operations. Currently he is the Director of the U.S. Navy’s Anti-Drug program.

Captain Thomas is a graduate of the U.S. Navy’s Line School, The U.S. Naval Post-graduate School, the Navy’s Legal School, the DOD Public Information Officer’s School, the U.S. Navy’s Command and Staff College, and the U.S. Naval Warfare College. He also holds a master’s degree in international affairs from George Washington University.

His previous published works include articles in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings and the Naval War College Review, as well as two series of weekly articles in the Navy Times on “Russian Communism” (1955) and “The History of Weapons” (1963).

Captain Thomas maintains “my most satisfying experience in the Navy has been dealing with people. I have managed to get along well with all of my juniors and colleagues – and with fifty per cent of my seniors. I never expected as much, and I don’t anticipate more!”

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Naval Institute Press

Annapolis, Maryland

------------------------------------------------------------

“THE HOOK” summer 1987, pp 21- 24

Acknowledgements:

CDR Bob Bennett, USN (Ret)

CDR Jack Bradford, USN (Ret)

CDR Art Elder, USN (Ret)

CAPT Ed Gillespie, USNR (Ret)

CDR Herb Sargent, USN (Ret)

CDR Melvin Scott, USN (Ret)

CAPT Bill Stuyvesant, USN (Ret)

CAPT Cal Swanson, USN (Ret)

--------------------------------------------------------------

Former Flying Midshipman CAPT Walter “R” Thomas, USN (Ret) received his wings in 1950. During his career he logged 6,000 hours in VS, VT, VR, VP and VQ squadrons. He was tactics officer of VP-9, the first P-3 squadron sent to Southeast Asia in 1965, and commanded Fleet Air Electric Reconnaissance Squadron Four 1969-70, flying EC-130Qs. Shipboard assignments included duty in USS Badoeng Strait (CVE-116), Boxer (CVA-21), and Okinawa (LPH-3). During his Washington tours, CAPT Thomas served in BuPers, OpNav and Chinfo. He is a graduate of the Naval Justice and Postgraduate Schools as well as the Naval and National War Colleges.

In his book, “From a Small Naval Observatory”, CAPT Thomas notes that his career “was so well rounded, it had no direction at all.” Upon retirement in 1981 he became executive director of the U.S. Navy Memorial Foundation. He left in 1985 to become a freelance writer, and now is working on his fourth book. He contributes frequent articles to naval magazines and to Navy Times.

Master of Ceremonies

Flying Midshipmen Reunion Washington, D.C

May 18, 1995

Now for a few new notes from our days in Pensacola. I realize that some of you older folk came from Ottumwa and other legendary sites but Tom Conway and I jumped on a train in Providence in August, 1948, and rolled down to Pensacola via New York, Washington, Atlanta and Flomaton, Alabama. Flomaton was culture shock. If the world was destined to become our oyster, 4 am in Flomaton was possum soup.

I had never encountered Alabama accents before; in fact, I didn’t understand anyone south of New Jersey. By the time we reached Pensacola, life seemed to become one huge, collective JETHRO bearing down on me. I still believe in 1948, no one in the south knew that “HARASS” was one word.

After arrival we were shoveled into an Officer Candidate Training Unit – supervised by chief petty officers who flunked “couth” – and poked by doctors who taught us to cough on demand.

We all signed an obscure contract that mentioned a commission as –ENSIGN – sometime – someday – maybe. No one ever saw a copy of that contract again. I suspect it was illegal; but it got us into Pre-Flight.

In Pre-Flight, we studied ancient engines, Morse code, strip navigation, bubble sextants and other Jurassic-age subjects. There was a course on “Principles of Flight”, about lift, drag, thrust and stuff – along with Robert Taylor and DILBERT movies on how to fly, or how not to fly. Wisely, we ignored all that once we started flying.

We spent a lot of time in the swimming pool learning how to swallow water – and escaping from the DILBERT DUNKER. This was supposed to build up our confidence for crashing into 6 feet of water at five miles per hour.

For recreation, we had the ACRAC, where we drank beer and lied to girls from the paper mill – you all saw the movie!

After Pre-Flight, we went to Whiting Field to display our stupidity to instructors who expected us to make an equal number of landings as take-offs. We were also sent off to solo – a test of faith over talent – not unlike a honeymoon. After soloing, we had to buy our instructors a fifth of booze – which was probably the reason they turned us loose – since we were not logically ready. But then if life was logical, men would ride sidesaddle. At Whiting, Frank Nulton learned to throw-up downwind which gave him an edge on us later aboard ship.

After Whiting, we went to Corry Field for instrument work where we learned to peek out of curtains and we started night flying to enjoy vertigo. From Corry we pressed on to Saufley Field where we tried to collide with each other and understand instructors trained in shrieking. We usually met over the Lillian Bridge in an aerial ballet for the genetically clumsy. We also flew gunnery runs over the gulf – shooting mostly fish and holes in our propellers.

Finally at Barin Field, we practiced carrier landings to prepare for the final fiasco – our first carrier catches at sea. At both locations we watched frantic LSOs wave flags around as if somebody cared.

After this we were ranked 1st class Midshipmen, and walked around with a sickening amount of self-admiration, also as if somebody cared! In truth, we were still as thick as 2 planks. We didn’t know it then, but we were entering into the golden years of Naval Aviation. Every good prop, turbo-prop and jet airplane of any ilk came on-line between the ‘40s and the ‘70s – and it all started with us – in Pensacola. Which may not have been the best days of our lives, but they were DAMN close!

BANQUET ADDRESS

50th Reunion, Flying Midshipmen

Pensacola, Florida

May 12, 1996

I’d like to welcome the more affluent [Flying Midshipmen] – the retired airline pilots. Quite a few here tonight. There’s an old phrase of a little child who said, “When I grow up, I want to be an airline pilot. Basic rule: you can’t do both, son!”

Now it’s been 50 years since we started blowing up barracks’ sinks and … uh … running panties up on the Admiral’s flags in the days of our LOUTHOOD here at Pensacola.

I’m going to remember a few things – mention a few things I remember from those days, my memory being what it is, or is not. But first, I want to remind everyone NOT to offer me a ride back to the hotel – I drove here. Memory and fatigue, two of the major problems as you grow older. A friend just said to me the other day, “If I go to the cleaners and gas the car on the same day, I need a nap.” I’m glad we have the 50th Anniversary here, instead of Washington, D. C., where we have to be a little more politically correct than we’re used to, especially in an election year. Bob Dole is trying to control his teenager – Newt. Newt, a man that really needs a Prozac moment. And the press is again reminding the President of his famous comment “I didn’t inhale and I didn’t like it.” Well, it’s obvious why he didn’t like it. This is not a Road to Damascus, revelation. And I can say this, a “Newsweek” Washington correspondent said, “President Clinton is feeling so confident about the election, that he’s started dating again.”

I’ve mentioned that I hit culture shock when I came here from clam digging country, in Rhode Island, 50 years ago. It’s only lately that places like Biloxi have come to be modern and learned such phrases as, “where the hell are the ATM machines?” And Trader John’s had yet to become the Mecca we all know – although you still have to decide whether to go there or comply with the health code. How many of you have been down there?

In 1948 I arrived in “Grits R Us Land” in Flomaton, Alabama – where they still celebrate the Fiesta of One Flag. Pensacola was not really urban in those days. And I’m fond of saying, “When you were invited to a house warming party in the 40s, you were expected to help take the wheels off. They did have liquor stores for the “Drunk on the Go,” – and the San Carlos Hotel was here then for a lot of our instructors from Whiting who came in on the weekends. Uh, the San Carlos has been demolished now; so I don’t know where the instructors go these days. Memories are a bit mellower now, as we forget unpleasant things like OCTU and Tarmac, Marine Drill Sergeants and maybe even Navy doctors who tried to twist our colons into semi-colons.

In Pre-flight, if you’ll recall, we studied stuff about as interesting as lint: Principles of Flight, Strip Navigation, which always was a favorite … it’s a distant memory, now, along with Morse Code. I did like the Dilbert cartoons. They kept the Burma Shave careers going for years, if you’ll remember them. Things like: “Lest you be a social bum; Always use your check-off, chum!” And they told us this time after time, and I guess eventually it got to us.

We marched to church on Sunday, if you’ll remember. I always mentioned this to my mother so she didn’t think I was getting in with the wrong crowd. For those into pain, physical fitness was fun. We had one instructor who knew only four words of the English language: what were they? [audience, in unison: “Get off the trampoleens!”] At the swimming pool we learned how to crash aircraft (?) into six feet of water – that did us a lot of good – and how to jump into simulated burning oil from a simulated ship, simulating saving ourselves. Ken Snoody had a problem with that in that he, like some others from the mid-west, couldn’t swim. On liberty a few studied graphic arts at the AMVETS. Paid for that, didn’t we?

When we moved on to Whiting Field, finally, we left Pensacola girls who took 45 minutes to apply makeup and met Alabama girls who used that time to clean their rifles. Our flight instructors talked to us through intercoms much like the microphones we have at these banquets.

And after we soloed we bought our instructors a bottle of booze – to sustain them between trips to the San Carlos. I’ve known at least two instructors who should have had their pictures on the gin bottles, saying: “Do you know me? I should be in Milton.”

We practiced landings at Pace and Wolf and Canal – fields that had been confiscated from soybean farmers, if you’ll remember. We also practiced acrobatics including, if you remember, whip-turn stalls, spins, and other great regurgitation maneuvers. It took Frank Nulton how many times?

At Corry we flew at night, scaring hell out of each other, We practiced instrument work there – listening to dit-dahs and dah-dits – which is Morse Code for As and Ns. Why we had to learn the other letters I’ll never know. Does anyone remember how to play a Crow’s Foot Range?” Does anyone care?

The Saufley Field challenge was to teach aerial ballet to the spatially handicapped. Each day we attacked each other over the Lillian Bridge. This was called “rendezvousing.” Tail chasing took on a new meaning. Later, on gunnery runs, we mostly painted the Gulf with colored bullets. We were great examples of why there can never be too much gun control.

At Barin Field we frightened a generation of LSOs before they flogged us out to the carrier where we would practice “slam-dunk” landings, “no-hook” approaches, and “disaster-oriented” wave-offs.

After our carrier quals we were genuine A-1, “Let’s Kick Butt,” First-Class Midshipmen. We became a unique band that banded together; as far as I’m concerned the greatest band of Naval Aviators ever. As I’ve mentioned before, Pensacola may not have been the best days of our lives – but they were damn close. Thanks for coming – have fun – happy anniversary!

MISCELLANEOUS

Was it practical to place Midshipmen in fleet combat units? Was it sensible? Was it even legal? We do know that it was cost effective. Flying Midshipmen received about $132 a month, including flight pay.

Well before the average future Aviation Midshipman faced such mundane problems as reduced pay and fleet duty, he had to complete two years of college. Academic failure posed the ever-present threat of being whisked into the fleet as an Airman Apprentice.

With academic success, however, the future fledgling received orders and a travel voucher sending him to Pensacola. It seemed as if the Navy's selection of transportation to Florida was either the cheapest train or the most disreputable bus available. Washington did not, in those days, toss money about loosely. In fact, the college student even had to attend summer school between his freshman and sophomore years ... government funds were not to be spent on idlers.

Once in Pensacola, the new arrival found that he was, above all else, slated to remain an Airman Apprentice until he was further evaluated as worthy of Aviation Midshipman status. The U. S. Marines were assigned this delightful task of determining "worthiness." Under this Officer Training Unit (OCTU) system, the new candidates were physically stressed and at least mentally abused under the watchful and reproachful eyes of their Marine Corps mentors.

During this initial training period in Pensacola, the rites of "Midshipmanship" were expected to be observed penitently. As the Aviation Midshipman was promoted through successive stages of flight training at Whiting, Corry, and Saufley Fields, his status progressed from Fourth to Second Class Midshipman. Within this structure, minor changes occurred in privilege and dress, all largely invisible. They consisted merely of switching collar anchors from one side to the other, or having a few extra hours of evening liberty. Cars were not permitted, nor overnight absences, allowed. For this first year of training, as Aviation Midshipman's life at Pensacola was neither migratory nor lived with wild abandon.

This monastery atmosphere changed significantly once the trainee qualified on the aircraft carrier and became a First Class Midshipman. This was the last stop at Pensacola before the student left for advanced flight training at Corpus Christi or other Texas bases. Unlike his recent contemporaries, a First Class Midshipman, during his last days of liberty in Pensacola had a position within the local hierarchy that seemed at least equal to a four star admiral. For the first time in his Florida exile, he could drink hard liquor, wear brown boots and the aviation green uniform, display anchors on both collars and remain off-base overnight every night.

Letter to Pat Francis

Ground Hog Time

I seriously doubt if I’ll ever get around to proof reading my own work, so you can imagine when I’ll correct any errors you may have made. Besides none of us like to have our faults highlighted.

As for glossary of aviation terms – normal, technical, localized and profane – it would take another lifetime, and I’m already wearing this one out. However, if you just jot down the jargon as you ramble across it, I’ll be glad to translate, e.g.

FCLP - Field Carrier Landing Practice; where we simulate approaches and landings at LOW (carrier type) speeds and try not to hit the cows.

SQUADRON STUFF:

VC – Composite Squadron; VF – Fighter Sqdn;

VA – Attack, VS – Anti-submarine; VP- Patrol;

VQ – Reconnaissance; HS/HC – Helicopter;

VR – Transport

(designates a unit, like VF-122)

OCTU: Officer Candidate Training Unit (where we went through physicals, drills and other irrelevant stuff for 2-4 weeks) – (circa 1946-1950) before entering pre-flight.

Line Puke: A surface [non-aviator (Black-Shoe)] officer. Almost any officer NOT an aviator.

Bravo Zulu: When a ship hoists the B and Z flags (thus Bravo Zulu) it is telling another ship, “Well Done.” Also used in letters and messages for the same compliment and is applied to almost everything.

Incidentally, I believe “The Hook” once published a glossary. Have Lou write them instead of hibernating.

Phone anytime.

Ciao,

/s/ Walt

P.S. Ask Lou to explain “Roger Ball” [Lou Ives never flew a “Roger Ball”--Only Paddles.]