Letter to Pat Francis

10 October 1995

Yes, the little OCTU story you asked about is mine.

Of the three other Midshipmen mentioned in the story, the only one I became personally friendly with was Walt Eells. Our paths crossed many times in training, and after we got our wings I saw him briefly at the Norfolk Breezy Point BOQ when we were all awaiting squadron assignments from COMAIRLANT in late 1949. He was an F4U Corsair pilot and went to a night fighter squadron at Atlantic City. I never saw him again, but heard he left the Navy after that tour.

I have been writing some memoirs for my children as the spirit moves me, using flight log books and personal diaries to refresh my memories of those long ago days. Since you asked, I’ll enclose a PBM sea story that is in reasonably good shape. It has some surplus words to explain the technical terms civilians might not understand. It also contains one error of fact: I can’t remember and can’t find out the voice call sign of the seaplane tender USS Currituck, so I invented one, “Sapphire”, to make the story sound right. I submitted the story to the Naval Institute for possible publication, but it’s not their style of material.

Sincerely

/s/ Harley

Harley D. Wilbur

A Sea(plane) Story

by Captain Harley D. Wilbur, U.S. Navy (Retired)

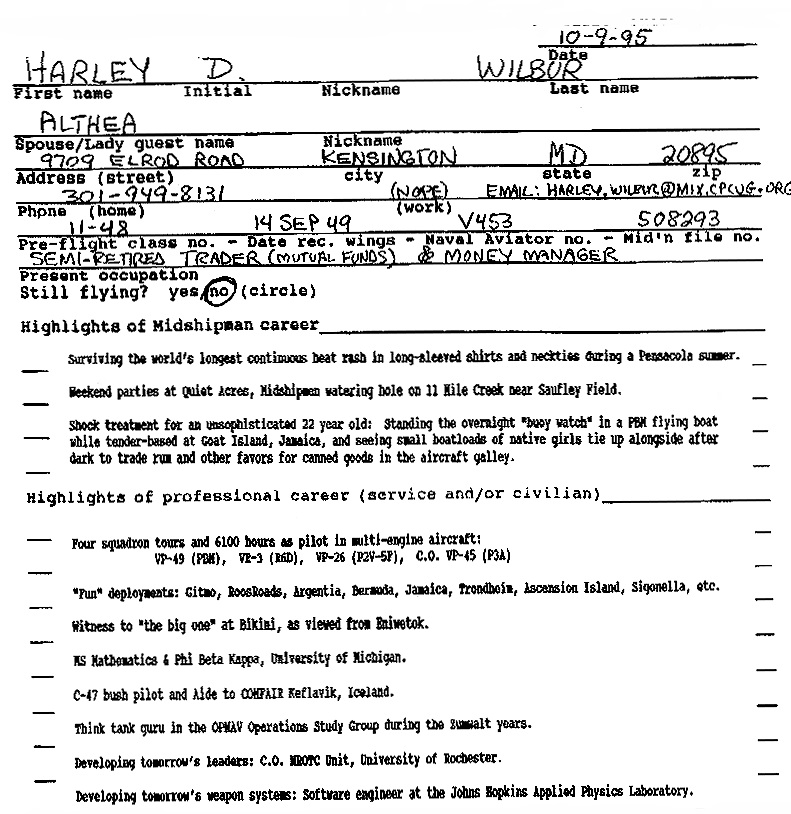

16 September 1952 was a day I won't soon forget. We were flying a PBM-5S2, a two engine, 30 ton Martin "Mariner" flying boat with a crew of ten persons: three officer pilots and seven enlisted men. We were in and out of clouds with moderate turbulence somewhere over the North Sea, and it was getting dark. Soon we wouldn't be able to see anything outside. There was some ice building up on the wings, we had no voice radio contact with anyone, and our navigator wasn't sure where we were. Our radar had just picked up what looked like the Norway coast, but what part of Norway was it? There were no satisfactory air navigation aids in the North Sea in those days. CONSOL, the British low frequency navigation system, was notoriously difficult to use, and because of the bad weather and the time of day, our radio direction finder was useless. We were stuck to rely on dead reckoning and our APS-31 antisubmarine radar, which wasn't very good for navigation.

Chief Hudson, our radioman, had CW Morse Code contact via HF radio with our seaplane tender, USS Currituck, at anchor in the northern part of Trondheim Fjord. From my point of view as pilot that wasn't a satisfactory substitute for voice radio contact from the cockpit, but it was better than nothing.

"Pilot, Radio. I have a message from base, sir," Chief Hudson said on the aircraft intercom system.

"What do they say, Chief?"

"1T65 is cleared to climb to and maintain 7000 feet."

When we used voice radio, our call sign was "Woodpecker One" or "Navy 85156", depending on whether we were talking to a military ground station or to civilian air traffic control. Shorter, more arcane call signs were used for Morse Code communications. Ours was "1T65". "T65" identified our squadron, Patrol Squadron Forty-Nine (VP-49). "1" was the side number of the aircraft. Our aircraft had a tail insignia with the letters EA followed by the side number, so another name for us was "EA-1". Confusing? Well, you get used to it. The squadron had 9 PBM seaplanes, and EA-1 was the Commanding Officer's aircraft. Because it was the skipper's crew, the individuals had been carefully picked, and I was very glad to have Chief Hudson as my radioman that day. He was a miracle worker at making contact when radio conditions were poor, which they almost always were in the North Atlantic.

"Roger, Chief. Tell them we are leaving 5000 feet now."

"Aye aye, sir."

I turned my ICS switch to HF radio so that I could listen to Hudson sending our reply on the ART-13 HF transmitter, which he controlled. My Morse Code skills were not very good, but I could recognize some of it: "Dahditdit Dit Ditdahdahdahdah Dah Dahditditdit Ditditditditdit." That translated to "DE 1T65", which meant "from plane No.1 of VP-49".

"Mixtures auto rich, flight."

"Mixtures auto rich, sir," came the confirmation. Chief Aviation Machinist Mate Martin, our Plane Captain, was at the Flight Engineer's panel. The PBM was designed to be operated by a team. The flight engineer, sitting at a panel about 15 feet aft of the cockpit, had a full set of controls for the two Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines that powered the big seaplane, including the fuel systems, oil systems, cowl flaps and engine starting systems. The only engine controls the pilots had were throttles, propellers, and ignition switches. The idea was that the pilots could concentrate on flying the airplane and looking outside, while someone else watched the engine gauges and made whatever adjustments were necessary. This concept no doubt came from the way it is aboard ships, where the people on the bridge conn the ship and send messages to the engine room when changes in power are needed. The PBM was, after all, a flying BOAT, wasn't it? I was too new in naval aviation then to question the PBM system, but in my next 20 years of flying I never again flew ANY aircraft where the pilot didn't have complete control over his engines.

"Set RPM 2600, Wes."

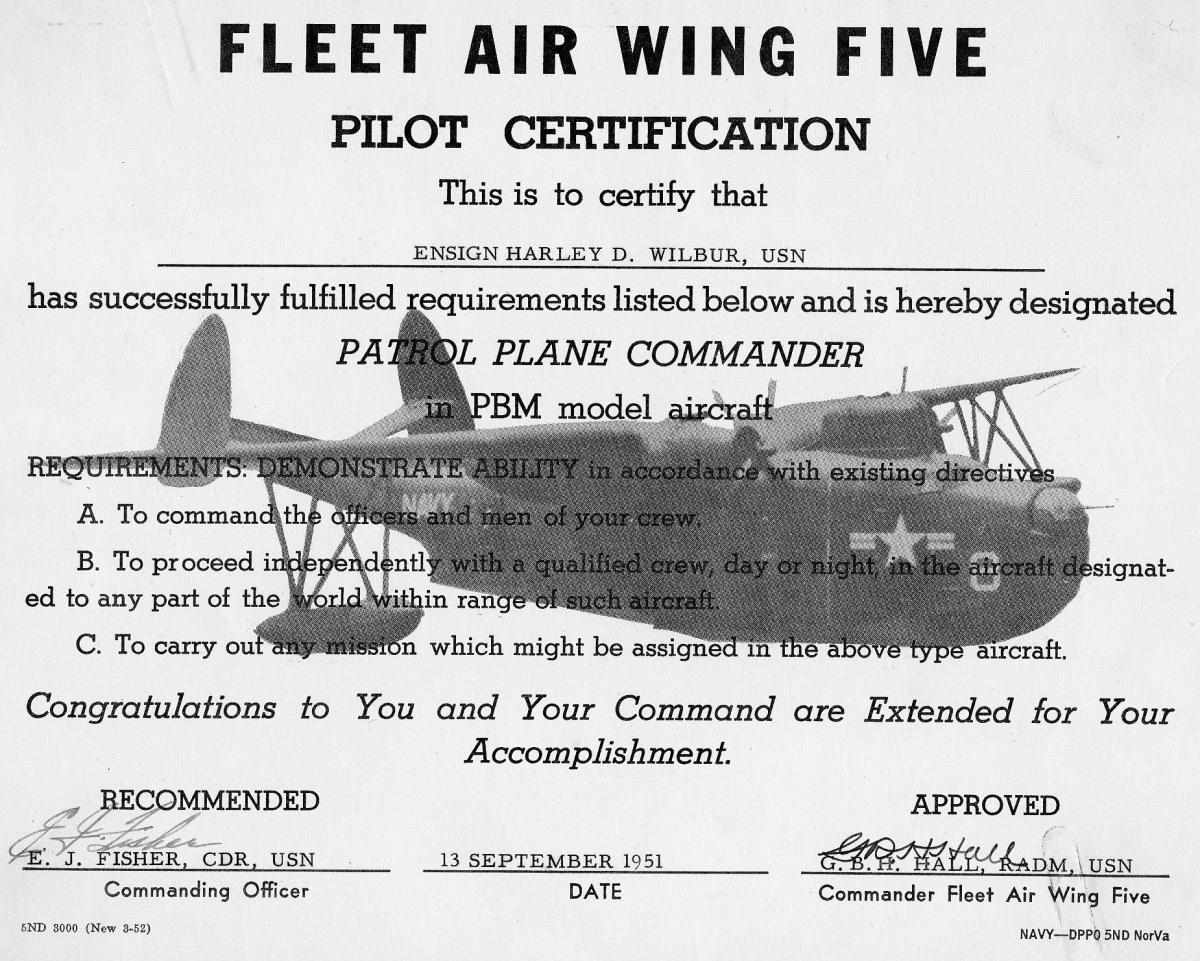

LT Wes Bogle was my copilot. He acknowledged the order with two clicks on his mike button and moved the prop controls to change engine speed from 1800 RPM cruise to the climb power setting of 2600. Although Wes was senior to me in rank ... he was a LT and I was still a LTjg ... he had joined the squadron only a few weeks before we left our Bermuda home port for the deployment to Norway, and had little experience in PBM aircraft. I had been in the squadron for 3 years and was a designated Patrol Plane Commander with about 1600 hours of pilot time in the PBM. I wasn't senior enough to have my own crew, but as copilot on the Commanding Officer's crew I was often assigned to fly as pilot in-command when the skipper was busy with other duties. Such was the case for this mission. I was 24 years old at the time.

The engines increased speed and I moved the throttles to set climb power for the change in altitude. Suddenly, BAM! BAM! BAM! One of the engines began to backfire and lose power. The racket was frightening, and we could all feel the aircraft shake.

"Flight, is that the starboard engine?"

"Yes sir, it's cutting out, sir."

Chief Martin, normally cool as a cucumber, sounded flustered. He looked upon the engines as part of his own family, and took great pains to ensure they were always in tiptop condition. Something like this was not supposed to happen. He took it as a personal affront when either of the engines misbehaved.

You can never be sure what's going to happen when an engine behaves like that. Every "BAM" of the backfiring was not only an assault on the ears, but felt as if someone had hit the airplane with a huge sledgehammer. One can only imagine the tremendous stress this put on the engine's complex moving parts. My first thought was to shut it down and feather the propeller before something catastrophic happened. This was not a happy idea, though. It was dark outside, the weather was rotten, we were half lost, and the only nearby sheltered water where we might safely land, Trondheim Fjord, had only a narrow opening to the North Sea and was ringed by mountains several thousand feet high. The PBM was an underpowered bird that did not perform well on one engine. It was doubtful that we could maintain enough altitude to safely cross the mountains, especially with a growing load of wing ice. Finding the mouth of the fjord at night with our radar was a virtually hopeless task. Even if we did find it, the ship was 50 miles up the dark fjord, and getting there without running into an island or a mountain was problematical. Shutting down the engine would probably force us to attempt a night open sea landing on one engine in the stormy North Sea below us, which was hardly a comforting thought. Flying boats were meant to land on water, but not on the extremely rough water found in a storm on the open sea. Even if anyone survived the landing, their chances of staying alive in those icy waters until dawn, when there would be some chance of being found by rescue craft, were poor. All these thoughts raced through my mind in a split second while I was trying to decide what to do.

This day had been wrong from the very beginning. It started with an unscheduled early get-up from my bunk on the USS Currituck with word from the squadron duty officer that EA-1 had been assigned to go with EA-6 to Sullom Voe, in the Shetland Islands, as soon as the weather improved. There were 22 aircraft based with the USS Currituck in Trondheim Fjord, 9 planes each from VP-49 and VP-661, and 4 Royal Air Force Sunderland flying boats from England. This was a big NATO operation called MAINBRACE. We were part of the Orange forces in the war game. Our job was to shadow the Blue fleet as it proceeded south toward the northern coast of Europe. The Orange commander had stationed the seaplane tender USS Timbalier at the Shetlands in a small, sheltered bay called Sullom Voe, and the Currituck forces kept a rotating detachment of 3 or 4 aircraft there during the exercise. Timbalier was a much smaller ship than Currituck, and had limited capability for aircraft maintenance, so when a detachment aircraft needed maintenance it flew a patrol and then landed in Trondheim Fjord. Meanwhile, a replacement aircraft flew a patrol out of Trondheim and landed at Sullom Voe.

The previous day my crew had flown a fruitless 10 hour mission in the northern part of our area. Much of the time we were at 500 feet or lower in a furious storm with 40 knot winds that whipped up a state 4 sea. At the conclusion of that flight EA-1 was hoisted aboard the tender for all-night maintenance. I was exhausted and hoped to sleep in, but another aircraft was needed at Sullom Voe, and EA-1 was the only available squadron aircraft with dependable radar. A crew was needed aboard the aircraft when it was put back in the water in the morning, and I was the pilot assigned for that job. With a skeleton crew, I refueled from the stern of the tender and then taxied to a buoy to tie up until launch time. The ship's Aerology officer said there would be bad weather all over the area that would delay our flight at least 24 hours, so I left my packed bags on the ship, thinking I'd get some more rest later. After tying up at the buoy I had to wait an hour for a boat to take me back to the ship. When I got there I was told we were ordered to depart for Sullom Voe immediately, so I grabbed my bags, rounded up the rest of the crew, got a quick briefing, and went back on the personnel boat to the aircraft. The skipper wasn't on this flight, so I was in command.

With EA-6 40 miles ahead of us we set a course for the Shetlands at 8000 feet in wet snow. About 60 miles from Sullom Voe we got word relayed by EA-6 on VHF radio that Timbalier had ordered us both to return to Trondheim. There was no precision radar to guide our approach to the Sullom Voe seadrome, and the weather there was too bad to safely land without it. By then we had been airborne almost 4 hours, fighting strong headwinds which cut our 120 knot cruising airspeed to about 90 knots groundspeed. We made a 180 degree turn, descended to 5000 feet, and were heading back to the Trondheim base in the gathering darkness when the engine trouble developed.

Rather than shut down the bad engine, I tried reducing its throttle setting. Happily, the backfiring stopped and it appeared to operate normally again. With what amounted to 1 1/2 engines we were able to maintain a slow rate of climb to 7000 feet. The altitude was necessary because of the coastal mountains that we had to cross.

"Radio, Pilot"

"Radio aye, sir"

"Notify base that we reached 7000 feet at time 1850 zulu."

"Aye aye, sir." Soon the dahs and the dits started up again on the HF radio circuit as Chief Hudson sent the message.

With a strong tailwind now pushing us, we knew we were getting near the ship, but still weren't certain of our position. Our radar indicated we were approaching land.

"Wes, take the controls. I'm going to try to raise the ship on VHF."

"Roger. I have the controls." I felt the control wheel wiggle as Wes signified that he was now flying the aircraft. I moved my control switch from intercom to VHF radio, and keyed the microphone.

"Sapphire Tower this is Woodpecker One, over."

No response.

"Sapphire Tower, Woodpecker One, over."

Still no response. Then there was a brief scratchy noise on the VHF receiver. That might be the ship trying to answer us. We were probably just beyond maximum VHF range. Another scratchy noise came through. Then, suddenly, a human voice was there.

"Woodpecker One, Woodpecker One, this is Sapphire Tower, Sapphire Tower. Do you read me? Over."

Whew! You could feel the atmosphere of relief in the aircraft. Everyone who had access to a set of earphones was listening to the radio.

"Roger, Sapphire, read you loud and clear now. We are over the coastline, heading zero three zero, at 7000 feet. Uncertain of our position. Be advised we have an emergency. Starboard engine operating on reduced power. Over."

"Roger, Woodpecker One. Turn right to heading zero niner zero for radar identification, over."

"Woodpecker One coming right to zero niner zero." Wes turned the seaplane to the new heading. A few seconds of silence followed, then:

"Woodpecker One, radar contact, bearing two two zero, six zero miles from Sapphire." To an aviator under stress, the words 'radar contact' can be the nicest sound in the English language.

"Woodpecker One, Sapphire Tower. Are you able to maintain altitude? Over."

"That's affirmative, Sapphire. We can't go much higher, but we are OK here. Over."

"Roger, Woodpecker One. I hold you clear of the coastal mountains. Now turn left to heading zero four zero. Descend to 5000 feet. This will be a surveillance radar approach to sealane one niner. Sapphire weather is ceiling 800 feet broken, visibility 3 miles in light rain, wind one seven zero at twelve knots, altimeter two niner eight eight. The crash boat has been notified of your emergency. Over."

.... And the rest of it was just a routine instrument approach and night landing on the waters of Trondheim Fjord, 400 miles south of the Arctic Circle in Norway.

The next morning I asked Chief Martin what he found wrong with the engine. It was a magneto failure. The magneto is a device that provides the electrical impulses to fire the engine spark plugs. Each engine has two magnetos and two sets of spark plugs, so losing one of them doesn't cause total engine failure, but does reduce the amount of engine power available.

Later in the Currituck wardroom, over coffee, I was telling the dramatic story of my hairy emergency to a couple of friends, complete with descriptions of how loud the backfires sounded, how the plane shook, and what a night open sea landing in the North Sea on one engine might have been like. LCDR John Leffen, our gruff Ops Officer, overheard and interrupted me.

"Wilbur," he said, with no sympathy in his voice, "Didn't you learn in ground school that an R-2800 engine can develop 60% of rated power on one magneto?"

I decided it was a good time to go to my bunk Operation Mainbrace Diary

Patrol Squadron FORTY-NINE

Trondheim, Norway

Sept-Oct 1952

Patrol Squadron FORTY-NINE Mainbrace Diary

by Captain Harley D. Wilbur, U.S. Navy (Retired)

Author’s note: This account of the VP-49 deployment to Norway in 1952 is reconstructed from a junior officer’s diary, pilot’s logbook, navigation forms, photographs, and some personal recollections.

In the summer of 1952 Patrol Squadron FORTY-NINE, based at Naval Station Bermuda, was abuzz with preparations for the forthcoming deployment to Norway in September. The purpose was a major NATO war game called Mainbrace. VP-49 was assigned to fly for the Orange Forces. Our job was to shadow and track the Blue fleet as it proceeded south toward the northern coast of Europe. In war game parlance “Orange” usually meant “enemy”, as distinguished from the color Blue that was reserved for the U.S. fleet. During the cold war the color red was not used to designate the enemy for obvious international political reasons. Among the Orange forces to carry out this mission were two USN seaplane squadrons, VP-49 and VP-661, along with four Royal Air Force Sunderland flying boats and two seaplane tenders, USS Currituck and USS Timbalier.

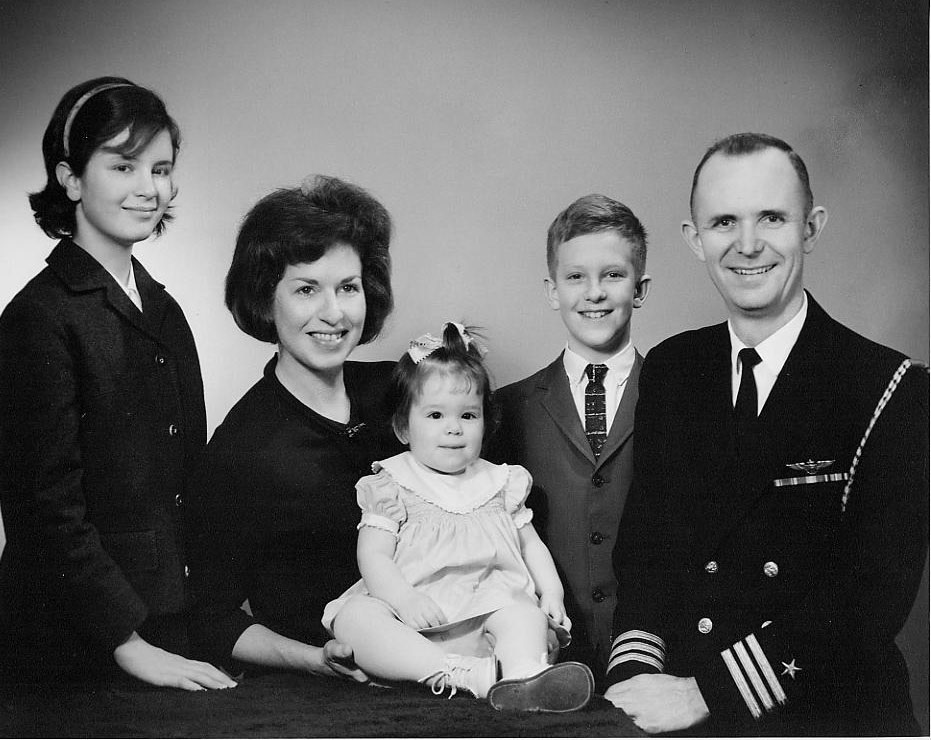

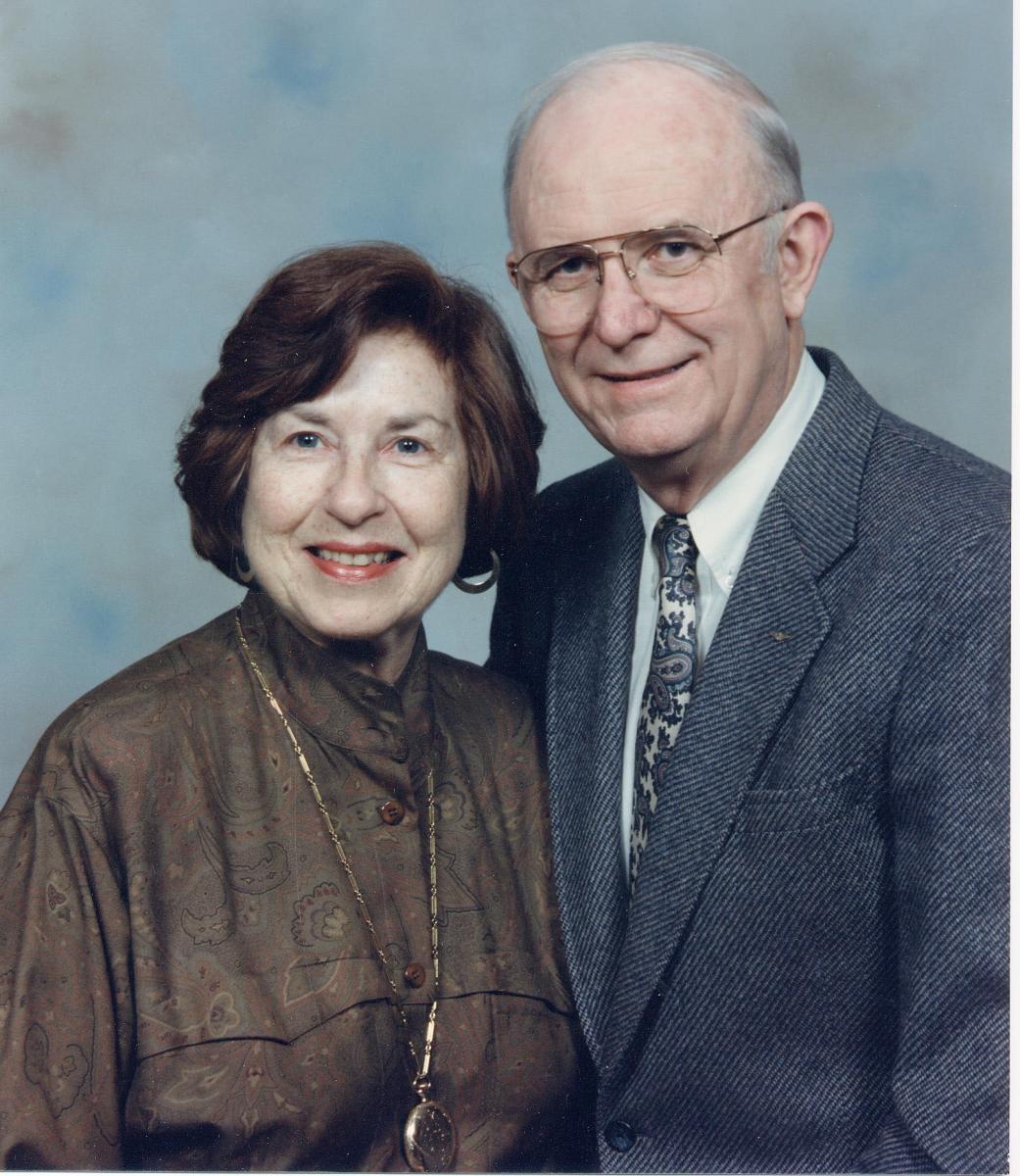

For VP-49 this was a big deal. Taking an entire seaplane squadron across the Atlantic was a major logistics effort and something that had probably not been done since the end of World War II. For me personally it promised to be an exciting end to my first squadron tour, which had started almost three years before. I expected orders to leave the squadron in November. Althea and I were already anticipating our trip home to the USA on the ocean liner Queen of Bermuda after 14 months of pleasant newlywed life in our little MOQ apartment on Naval Station Bermuda.

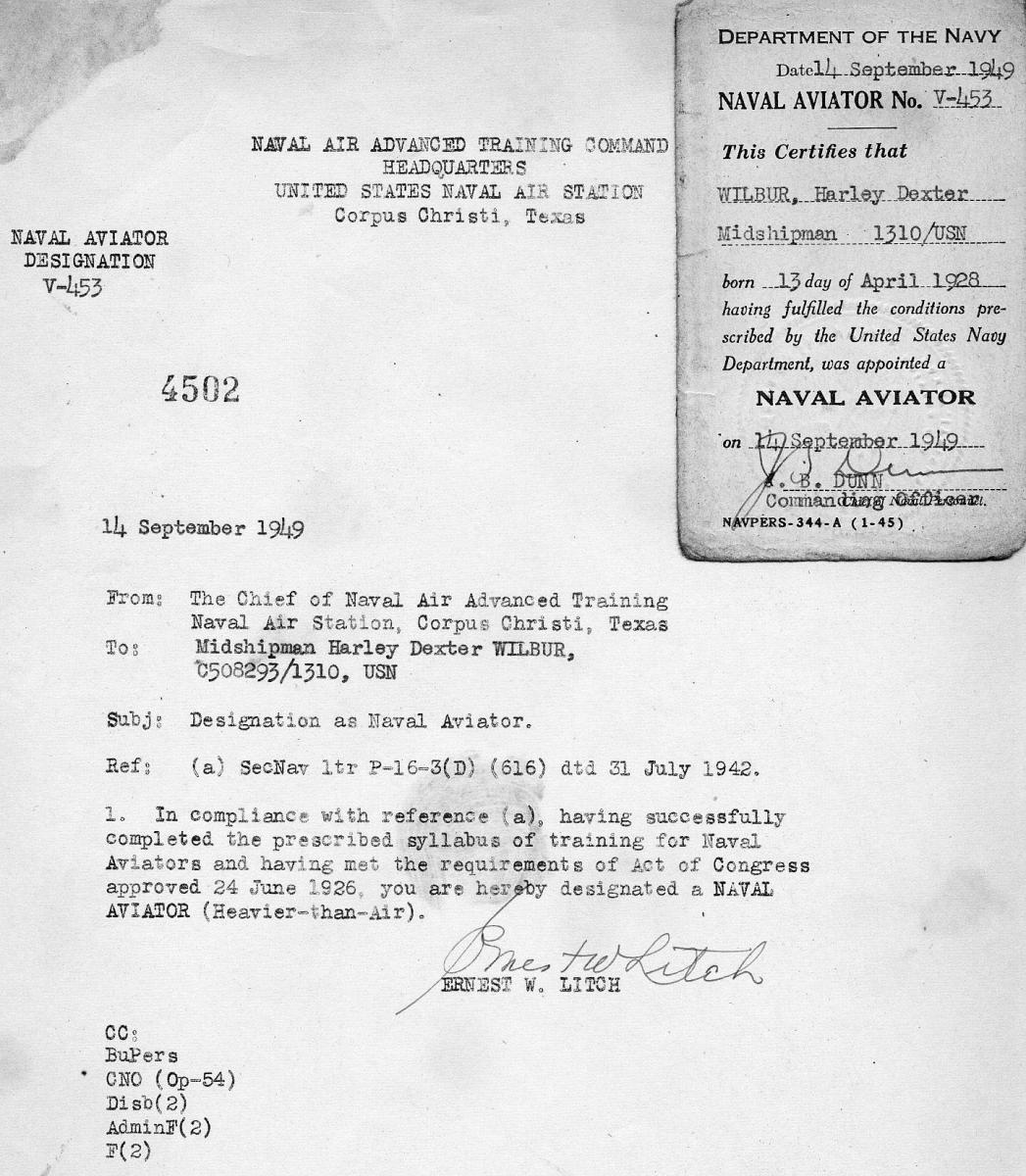

Imagine my surprise, then, on 11 August 1952 when my boss, squadron Material Officer LT Paul Parks, handed me the latest mail from BuPers: my change of duty orders. The first sentence stunned me: “When directed by your commanding officer in September 1952, … proceed to NAS Corpus Christi, Texas, and report to the Chief of Naval Air Advanced Training … etc. etc.” September! That was our month to be in Norway! Paul told me the skipper wanted to see me, and I was in his office as fast as I could get there. Just a week earlier CDR Jim Lynch had relieved CDR Ellis Fisher as C.O. VP-49. As an experienced first tour pilot in the squadron I was a designated Patrol Plane Commander and had been CDR Fisher’s copilot. The new skipper told me he wanted me to continue in that position for the Mainbrace operation. Therefore, he would ask Bupers to delay my squadron departure date from September to October. Nine days later I received an official modification to my orders: Instead of September, my detachment date was changed to “about 1 October”, which meant I would have to leave by October 10th.

This enabled me to make the Mainbrace deployment, but also meant that we would not be able to take the Queen of Bermuda back to the USA afterward because there was no Queen sailing that would be compatible with my orders. This was a personal disappointment for Althea and me. As it turned out, Althea left for her parents’ home on 31 August and I closed out our Bermuda apartment two days later. I didn’t realize until some years later what a rare opportunity it was for us to start our marriage on that delightful island. Nothing like it ever happened to us again.

Now for the Mainbrace story, in diary format:

Tuesday, 2 September 1952

The alarm clock got me out of bed at midnight. I packed the few remaining items and vacated NavSta Bermuda Quarters 131B forever. Our once well-lived-in apartment was an empty, ghostly shell when I left. The skipper’s airplane, EA-1, departed Bermuda at 0200. The officer crew was CDR Lynch, PPC; LTJG Wilbur, copilot (PPC); LT Wes Bogle and ENS Bill Greenleaf, pilot/navigators. The first leg of the trip was an 8 hour flight to Naval Station Argentia, Newfoundland. Earlier in the summer the squadron lost an airplane (but fortunately no crew members) in a bad weather landing at Argentia, so we all have some bad vibes about the place. This time the weather, 2000 foot ceiling with drizzle, presented no problems. As usual, it seemed cold in Argentia after coming from Bermuda. It would get a lot colder before this deployment was over. This was the last time any of our airplanes would be hauled out of the water onto the security of a seaplane ramp for more than a month.

Wednesday, 3 September 1952

We were airborne from Argentia at 0130 this morning, enroute to Reykjavik, Iceland. This was the longest leg of the trip, about 1450 miles. There is usually a strong wind blowing from Newfoundland to Iceland, which minimizes travel problems for eastbound flights. (Westbound trips are another story, as we would later learn.) Nevertheless, we topped off with full tanks of fuel, including the one bomb bay tank that each aircraft carried. Our best navigation aid, Loran, did not provide good coverage for much of this trip, and if Iceland weather turned sour it was a long way to any alternate seadrome. This was a 61000 pound takeoff, which is heavy for a PBM, but it went without incident.

The movement plan provided for the small seaplane tender, USS Timbalier, to service us at Reykjavik. Timbalier was an old friend from Caribbean deployments and had always provided us with cheerful, competent and comfortable service. Since it could not easily handle more than six aircraft at a time, the two PBM squadrons had to stagger their arrivals through Iceland. The large tender, USS Currituck, had crossed the ocean a couple of weeks earlier in order to set up the seadrome for our main Norway base in a fjord about 40 miles north of the town of Trondheim. As soon as all the aircraft cleared Iceland, Timbalier would proceed to the Shetland Islands to set up another seadrome there in a bay called Sullom Voe, for use during Mainbrace.

The movement plan provided for the small seaplane tender, USS Timbalier, to service us at Reykjavik. Timbalier was an old friend from Caribbean deployments and had always provided us with cheerful, competent and comfortable service. Since it could not easily handle more than six aircraft at a time, the two PBM squadrons had to stagger their arrivals through Iceland. The large tender, USS Currituck, had crossed the ocean a couple of weeks earlier in order to set up the seadrome for our main Norway base in a fjord about 40 miles north of the town of Trondheim. As soon as all the aircraft cleared Iceland, Timbalier would proceed to the Shetland Islands to set up another seadrome there in a bay called Sullom Voe, for use during Mainbrace.

The flight to Reykjavik took about 10 hours. The weather was good, though cold, and the trip passed without incident. Upon arrival we refueled from the stern of the tender and then tied up at a buoy. Bill Greenleaf drew the buoy watch, with temperature in the low 40s and a chilly north wind blowing. On the ship the rest of us ate, had a briefing on tomorrow’s hop, and hit the sack early.

Thursday, 4 September 1952

Got up at 0445, with time enough to drink a cup of coffee, dash off a postcard home, and get a weather briefing before taking a boat out to our airplane. EA-1 was airborne with the sun at 0630, with Trondheim just 6½ hours away. At our cruising altitude of 7000 feet we were clear of clouds with an outside air temperature of -7 degrees centigrade. EA-4, following us in the clouds at 5000 feet during the latter part of the trip, picked up enough ice to carry away her HF antennas. Since the only radio she had left was line-of-sight VHF, she joined up on us for the final part of the trip. We couldn’t contact anyone on the radio for an instrument approach to Trondheim, but there was a 1500 foot ceiling so we let down through a hole over the ocean and then flew up the fjord until we found USS Currituck.

I drew the buoy watch tonight, since the plane had to be turned up and taxied later to check one engine for an oil leak that had developed during the flight. It proved to be a bad leak, and so we were scheduled to be hoisted aboard the ship for a check the next morning. The air temperature was in the 40s with a cold west wind blowing. We couldn’t get the aircraft heater working, so it was a chilly night for those of us on the buoy.

Friday, 5 September 1952

EA-1 was hoisted aboard the tender at 1000 this morning. It was my first time to observe such an operation, a marvel of careful teamwork. The crew then swarmed over her to pull the check. We were scheduled to be put back in the water this evening, but difficulties with the oil leak kept the check crew working until well into the night. Many of the officers and men went ashore into Trondheim on liberty, but I decided to wait until my next opportunity. The senior officers were busily making plans for next week’s familiarization flights, and I made myself available for various odd jobs that had to be done.

Saturday, 6 September 1952

Various delays caused EA-1 to remain on the ship until 1400. When we finally did get it back on the water, we went out for a 2½ hour familiarization flight around the local area. The sun came out and the scenery around the fjord was beautiful to behold. We returned long enough to refuel from the tender and eat supper, then went out again for our night fam, another 2½ hour flight. The main purpose of these local flights is to become familiar enough with the fjord so that we can make an instrument approach comfortably if that should become necessary after Mainbrace starts. The skipper and I both think we have that problem pretty well in hand now.

Sunday, 7 September 1952

Sunday, 7 September 1952

This was another partly sunny and beautiful day, and the skipper, Wes Bogle and I flew another 2.7 hour fam flight this afternoon. Bill Greenleaf had the duty and did not join us. I had the buoy watch tonight, and took a boat out to the plane about 1830. It was another cold night.

Monday, 8 September 1952

I came in off the buoy watch about 0700, thoroughly chilled, but was warmed up by a hearty breakfast in the Currituck wardroom.

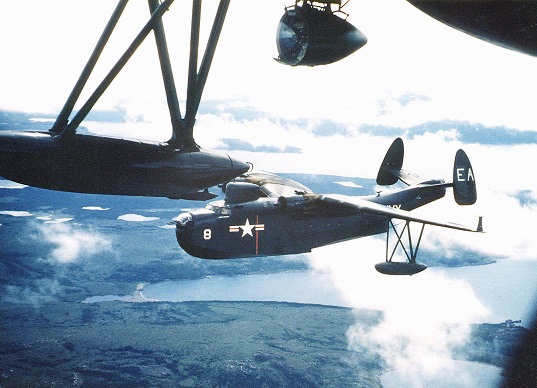

Today was liberty day, and a group of us, including Jess Taft, Jack Pickens, Wes Bogle, John Leffen, Frank McCoy, KC Campbell, Dick Klabo, Paul Parks & I, took the 1230 boat to the nearby village of Skogn. There we piled into buses arranged by the ship for a thrilling 90-minute ride into Trondheim.

There were two aspects to the thrills of the ride. One was the high rate of speed at which the bus traveled on very narrow, scary two lane roads; the other was the breathtaking scenery along the route. It was another sunny day, and the beauty of the countryside defies description. We arrived in the town of Trondheim about 1430, and spent the afternoon shopping and walking around, seeing the sights. The buildings, mostly frame construction, are not unusual, but the people are a different matter. They all have rugged features, white skin with red cheeks, and are quick to smile and be friendly. They knew us to be foreigners by our uniforms, and made us feel welcome in their town, which has a population of about 50,000. None of us could speak Norwegian, but the language barrier was not a big problem because many of the shopkeepers, clerks, waiters, etc., spoke enough English to understand us. At one point a group of children crowded around us on the street and we gave them candy, gum and whatever other goodies we had with us.

A British lady opened a conversation with us in English, saying that the Norwegian children are well fed but the children in Great Britain are the ones who need candy handouts because food is still scarce there. Our evening activities consisted of drinking and eating in the various hotels and restaurants. Food was plentiful, tasty, and very reasonable in price.

Frank McCoy and I (the party poopers) decided to take an early bus back to Skogn, but there weren’t enough people interested in that to make a busload, so we all had to wait until the last buses departed at midnight. I didn’t make it to bed until 0245, thoroughly exhausted.

Tuesday, 9 September 1952

Crew 1 had another liberty day today, so I was able to sleep in this morning. I missed breakfast, but my morning hunger pangs were soothed by mail call, at which I received three letters. We are told to expect mail only once a week during this deployment. Given the circuitous ChiSkogn, Norway: USS Currituck and PBMs at anchoref Hudson said on the aircraft intercom system. rouSkogn, Norway: USS Currituck and PBMs at anchortSkogn, Norway: USS Currituck and PBMs at anchore mail must take to reach us this does not sound unreasonable.

Jess Taft and I decided to do some walking around the local countryside this afternoon. We took the 1300 boat to the dock at Skogn, where there always seems to be lots of activity. The local villagers are curious about our airplanes, tied up at buoys between USS Currituck, and the shoreline. The scene is like that of a mother hen and her chickens. Chickens have to eat, and the villagers quickly learned that they could row their boats out to the airplanes and trade their fresh farm bread, butter and eggs for our aircraft galley supplies of canned fruit and coffee. This informal Norwegian commerce is favorable to both sides and provides a break from boredom for the crews on buoy watch. It has much more class than the commerce we saw during our Goat Island, Jamaica, deployment a couple of years ago. There the natives tried to exchange homemade rum and the nighttime “services” of their young ladies. (The latter commerce was done only during hours of darkness. The Norwegians use the daylight hours.)

Jess and I set out from Skogn on foot along the road to Levanger, a larger village about 5 miles away. We were marveling at the beauty of the countryside and taking photos as we walked, when we saw a bus coming along behind us. It turned out to one of the two scheduled runs per day along this road, so we hopped aboard and rode into Levanger for 75 ore, about 11 cents US. In the village we walked around taking pictures and “looking” for a while, then stopped

in a little Kafe for coffee and pastries. We also spent some time in a bookstore, and counted no less that 6 bakeries (“Bakeri”) in the town of 1400 people. The Norwegians evidently like their pastries. We continued our travels around the village, had dinner in the only hotel about 1700, and then returned to the Skogn dock via taxicab.

Wednesday, 10 September 1952

Nasty weather entered the scene today, and I was glad I had no further interest in going ashore. I attended one officers’ meeting to discuss operational aspects of Mainbrace, and spent the rest of the day writing letters and studying my Navy correspondence course “Foundations of National Power”.

Thursday, 11 September 1952

Another day of inactivity. It was the last liberty day before Mainbrace begins, but not many officers availed themselves of the opportunity. I continued my ship-board activities of writing letters, studying my correspondence course, and reading. There was some excitement for us to watch when four RAF Sunderland flying boats arrived to join our group. One of the things we noted right away was the different RAF attitude towards the aircraft buoy watch. They simply don’t believe in it. When they arrive after a flight, the last man out locks the airplane door and everyone goes into the personnel boat. If the airplane drags its buoy or sinks overnight, so be it. Ah! The civilized British!

My turn again on the EA-1 buoy watch tonight. Brrrr. Cold night.

Friday, 12 September 1952

Briefings most of the day today, in a feverish effort to pass out last minute operational information. Compared to past squadron-level briefings, this morning’s major briefing by the ship’s officers was poorly prepared, and necessitated another squadron briefing this afternoon to cover some neglected points. VP-49 always seems to get more excited about these operational details than other units do. Do we set our sights too high? Well, we are the “E” squadron after all.

At the skipper’s request, EA-1 was scheduled for the first Mainbrace patrol tonight, so I attempted to get some sleep this afternoon. We were briefed at 1930 and were airborne for the 12 hour flight at 2230.

Saturday, 13 September 1952

Our flight was characterized by lack of contacts and considerable doubt about our navigational position most of the time. Not completely lost, just imprecise and uncertain. The radio navigational aids in the area are very poor, skies were overcast, and we had to rely on dead reckoning most of the time. The driftmeter and visual estimates of surface winds are a navigator’s best friends in this situation, but they are difficult to use at night. The skipper was pleasant and cheerful throughout the flight. He doesn’t let himself get upset when things go wrong, and is very pleasant to fly with.

We landed about 1015 this morning. Benzadrene tablets kept us awake during the night. After debriefing and the noon meal, their effect began to wear off, and I was ready to sleep. Slept from 1400 to 1730, woke up for the evening meal, and then slept again from 1830 to 2400. At that hour I got up for the briefing for our next flight, only to find that we had been removed from the schedule because of radar troubles. The mail was in, however, with my first letter from Althea. Still wide awake, I wrote a reply and then read for a while until I got sleepy again. Finally went back to bed about 0200. What a crazy schedule!

Sunday, 14 September 1952

Crew 1 had standby duty today. For most of the day there was no action, just an occasional briefing, and reading, studying, and sleeping. Once we got as far as loading the airplane, casting off and taxiing around the fjord, but then the mission was cancelled and we returned to the ship. Cold, rainy weather.

One of the things I notice at our briefings is that the RAF pilots have a much more relaxed attitude toward things than we do. For example, we USN types fuss a lot about having a detailed procedure for what altitudes to fly during instrument flight conditions in the operating areas. The idea is to have altitude separation to preclude airplanes running into one another in the clouds. The RAF types are impatient with us about this. Their attitude is that since there are so few airplanes in this part of the world, it just isn’t worth bothering about. It would be a tremendous stroke of bad luck if two airplanes did meet at the same altitude in a cloud. The RAF position seems to be, if that happens, aircrews should just keep a stiff upper lip, “be British”, and crash and burn with dignity.

Monday, 15 September 1952

We finally got a definite flight early this morning. Had a 0300 briefing and were airborne at 0430. The skipper had a social engagement last night, so Wes, Bill and I took the patrol. It was ten hours of really bad weather and no contacts. The radar failed, and for about 4 of the hours we flew a search pattern under clouds at 500 feet over a phenomenal sea whipped up by 40 knots of wind. It was a terrific strain for all of us. The Norwegian Sea can be a rough place for a sailor to ply his trade!

After landing and tying up to a buoy this afternoon we learned that EA-1 was to be brought aboard the ship tonight so that she could be checked in order to fly again tomorrow. I went out with the plane director and his boats to witness the operation of hoisting the bird aboard. It is an interesting evolution with emphasis on teamwork, precision, and care to avoid accidents. Most of our planes are having radar troubles. Those of EA-1 are less serious than some of the others. The few planes with workable radar have to bear the brunt of the flying. The new APS-31 antisubmarine radar in our PBM-5S2 aircraft seems to be much less reliable than the old APS-15 radar we had in the PBM-5S. The weather remains lousy … rain all the time.

Tuesday, September 16, 1952

It was decided that EA-1 would accompany EA-6 to Sullom Voe today, so I packed my bags. Then aerology said it would be at least 24 hours before we could go because of bad weather all along the route and at both terminals. After that EA-1 was hoisted off the ship and I had to taxi her back to the buoy, where I waited for two hours for a boat back to the ship. When the boat finally came it brought orders for us to leave for Sullom Voe ASAP, so I returned to the ship to pick up my bags and the rest of the crew. We were briefed, took a boat back to the plane, and soon were airborne. (The skipper was not with us.) With EA-6 40 miles ahead of us we flew toward the Shetland Islands at 8000 feet, soon encountering wet snow that left a moderate coating of ice on the plane. We easily cracked it off the airfoils with our deicer boots. About 60 miles from the Shetlands, half lost, we got word from EA-6 that USS Timbalier ordered both of us to return to Trondheim because of bad weather at Sullom Voe. It had taken us almost 4 hours to get this far. Upon turning around we picked up a strong tailwind. Soon we had the Norway coast on radar, but were in the clouds and couldn’t determine our exact location. 100 miles or so from Trondheim USS Currituck sent us a CW message to climb from 5000 to 7000 feet. Upon adding climb power our starboard engine began to backfire and cut out. This was really the last straw in a fouled-up day! We got it working OK again at reduced power, but it was a scary few minutes when it happened. We finally got voice radio contact with the ship on VHF and made a night surveillance radar instrument approach to the seadrome. On the water the starboard engine quit completely during our buoy approach. The problem turned out to be a magneto failure.

Wednesday, 17 September 1952

Wednesday, 17 September 1952

While Chief Martin and the mechs worked on the plane all day, I stayed on the ship and watched the hands of the clock go around. I tried studying, reading, and writing letters, but nothing held my interest. Letdown from the exciting day yesterday, I suppose.

I had the buoy watch tonight. It was difficult to sleep because of the noise of the auxiliary power unit. The APU had to be kept running until 0200 to supply power to the radar, which was being worked on again by the techs. Radar remains the biggest single problem for all the planes.

Thursday, 18 September 1952

I was up at 0530 this morning to turn up and check out the engines. The early start was of no avail, though. The engines are OK, but the radar is still down, so we won’t be flying today. The 0630 boat from planes to ship was an hour late, and it rained steadily as we went from plane to plane to change the buoy watch. When we finally reached the ship I was soaked, hungry and thoroughly irritated.

I became Squadron Duty Officer about noon. That kept me busy for the rest of the day and most of the night. Aboard ship the SDO is the focal point of all squadron activities. He must coordinate operations and maintenance, schedule flights, “pass the word”, order flight rations, boats, sonobuoys, etc. He is the general handyman to whom everyone runs when there is a need or a problem. During an operation like Mainbrace the SDO is very busy all the time.

Friday, 19 September 1952

After Jack Pickens relieved me of the SDO duty this morning I went to bed and slept until lunch, but not very soundly because of the high level of noise in the bunkroom. The EA-1 radar was finally fixed, and we were scheduled to go out on patrol at 1700. EA-8 and EA-9 (McCoy, Ferrucci, Schneider, et al) returned from Sullom Voe after being relieved by EA-2 and EA-5 this morning. Later Jess Taft had to take EA-3 to Sullom Voe also, as the center of Mainbrace activity moved south out of the Norwegian Sea into the North Sea.

We were briefed at 1630 and took off at 1800 for our all night patrol. As has often been the case in this operation, the briefing was (in my opinion) inadequate. The ship briefers do not have complete information and the pilots have to dig for themselves to get such essential information as IFR altitudes and call signs of other airborne aircraft in the area. For this mission Wes Bogle and I navigated while the skipper and Bill Greenleaf did the flying. We found the task force we were looking for, but nothing else, and returned to Trondheim Fjord about 0500. 10.5 hours flight time.

We were briefed at 1630 and took off at 1800 for our all night patrol. As has often been the case in this operation, the briefing was (in my opinion) inadequate. The ship briefers do not have complete information and the pilots have to dig for themselves to get such essential information as IFR altitudes and call signs of other airborne aircraft in the area. For this mission Wes Bogle and I navigated while the skipper and Bill Greenleaf did the flying. We found the task force we were looking for, but nothing else, and returned to Trondheim Fjord about 0500. 10.5 hours flight time.

Saturday, 20 September 1952

I had breakfast and then slept through lunch. Spent the afternoon reading, doing a little squadron Material Department work, and playing chess with Frank McCoy. Mainbrace has essentially ended for the Trondheim task group, but patrols will continue out of Sullom Voe. Jess Taft unexpectedly brought EA-3 in from there tonight when the Sullom Voe weather closed in while he was on patrol.

Sunday, 21 September 1952

This was our last day in Trondheim fjord. I spent most of it reading, and writing letters. There was some excitement for us to watch when one of the RAF Sunderlands, with one of its four engines out of commission, attempted to make a 3-engine take off for its trip home. It needed an engine change, which Currituck could not handle. It made several attempts, running on the step in large circles around the fjord while we watched from the ship. The bad engine was an outboard engine, and the pilot couldn’t get up enough speed to get airborne on his circular course. When last seen, the big white bird was taxiing south in the fjord, heading in the general direction of the town of Trondheim, 50 miles away. We were told the RAF would do the engine change at a Norwegian facility there.

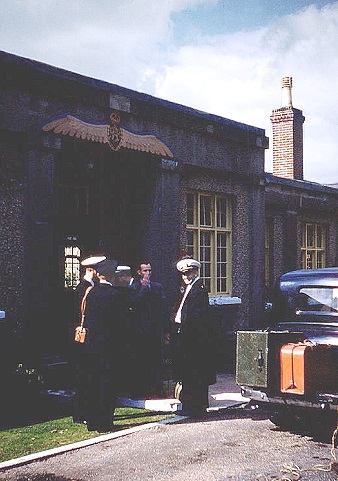

I took a boat out to EA-1 this afternoon to spend an hour or so getting our charts and airways publications in order for the trip to England tomorrow. The plan is that we will move the aircraft to the RAF base at Calshot, on the south coast of England near Southampton. We will remain there (and have some liberty) while our seaplane tenders reposition themselves to support us on the trip home. USS Currituck will move to the Firth of the Forth to set up a seadrome for us in the harbor of Edinburgh, Scotland, while USS Timbalier goes back to Reykjavik to provide us a staging base there.

This evening there was a briefing at which a RAF officer gave us a great deal of information about Calshot and flight procedures in the surrounding area. As I listened to all the questions that were fired at him I couldn’t help thinking how belligerent we Americans sometimes are. By the questions they asked, some of those present sounded like they had lost all sense of proportion, and that they believed we were doing the British a favor by visiting them at Calshot, instead of simply receiving their gracious hospitality. I wonder what they think of us?

Crew 1 moved all its gear into a plane personnel boat and started loading the airplane about 2300.

Monday, 22 September 1952

EA-1 departed Trondheim fjord at midnight, bound for Calshot, England, on what should have been a routine 7-hour flight. Our navigation got fouled up again, though. We managed to drift 100 miles east of course and made our first landfall over the Netherlands coast. Having thus fixed our position, we made our way to Calshot and landed there in Southampton water about 0800. It was decided that Bill Greenleaf would have the buoy watch for the next two days while the skipper, Bogle and I went on liberty. After stowing our gear in rooms at the RAF Calshot base, we went ashore in our blues, ready for the trip to London. I accompanied Calhoun, Ellis, Phelps, Leffen, Bradley and Edwards in a taxi to Southampton, where we caught the 1130 train to London. The skipper was waiting for us at London’s Waterloo Station 90 minutes later, to tell us that hotel rooms were very difficult to find. A London bobbie came to our rescue and found us rooms at “Astoria Chambers”, a private hotel that was little more than a rooming house. The skipper and Dr. Bill Ellis managed to find a room in a real hotel nearby. The focus of many of the officers was the famed London night life, but I decided that wasn’t my cup of tea. My interest was the day life. I bought a London guidebook for 5 shillings, and after reading for a while to plan tomorrow’s sightseeing trip, I went to bed about 1800, dead tired.

Tuesday, 23 September 1952

Tuesday, 23 September 1952

After breakfast, included in the price of the room, I consulted my trusty guidebook and took a subway to Waterloo Station, where I checked my bag. Then I took the subway back to Picadilly Circus to start my sightseeing tour. First stop was Buckingham Palace, and as luck would have it I arrived just in time for the changing of the guard. I walked back through St. James’ Park to Westminster Abbey, and then to the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben. Walked up Whitehall, looked at 10 Downing Street, and saw the Horse Guards and Trafalgar Square. Stopped at a little French restaurant called La Coquille for lunch (no beef, just turkey, chicken, duck or fish), and then took a subway to the Tower of London.

Spent a while listening to one of the Beefeaters give his talk about the tower, then took a water bus up the Thames to Westminster again. Hopped a bus this time to visit the British Museum, then by subway to Grovesnor Square to look at the statue of Franklin Roosevelt. I met Bradley, Clinton and Brown there. We all had tired feet by this time (1600), and so we took a taxi to Winfield House in Regents Park, the U.S. Armed Forces Officers Club, where we had a beer and dinner. Ellis stopped by while we were there, but left soon for more London night life. I left in time to get a subway back to Waterloo Station and catch the 1930 train to Southampton. This took more than 2 hours, and the bus to Calshot took another hour. Once there, I had a sherry at the RAF Officers Mess and then went to bed. So much for the day in London. My aching feet!

Wednesday, 24 September 1952

Wes went to the plane and took over the buoy watch this morning, as Bill Greenleaf and the other offgoing buoy watch people take their turn at London liberty. The skipper and other senior officers returned from liberty about 1030 and soon went into conference about the weather situation. The Edinburgh weather is bad, and so we will add an extra day to our stay at Calshot.

To me an impressive thing about this RAF base is the boat situation. They not only have many more boats than I have seen at any comparable US base, but also boats that are more sturdy and dependable than our rearming boats and plane personnel boats. The British find our policy of keeping a 24-hour watch aboard each aircraft rather silly. Perhaps by the time we leave they will think it worse than silly. They give us good boat service, and with 14 aircraft on the water we are keeping their boats very busy!

A word about the British breakfast: Standard menu at RAF Calshot is very strong tea, stewed tomatoes, and various breads and pastries. I missed my morning coffee!

The British are very friendly to their American visitors. We are always in uniform and easy to recognize. Just before teatime this afternoon Jack Pickens and I started out on a walk. About ½ mile down the road a car stopped beside us and the man in it asked if we would like to come out to his house for tea. We gladly accepted. He drove us to his home in the nearby town of Fawley, where we met his wife and two young daughters, and had tea and pastries. The family name was Davidge. I’d guess the man is in his late 30s. He works as a repairman in the Fawley Radio Shop, so we had something in common to talk about. (My father has a radio repair shop in Royal Oak, Michigan.) We stayed about an hour and then Mr. Davidge took us back to the RAF Officers Mess. This experience was a most pleasant interlude for Jack and I.After dinner I joined other hardy souls braving the wind and the rain in a boat to post the night’s buoy watch. A cold storm blew all night and I was glad to have a warm sleeping bag on the airplane.

Thursday, 25 September 1952

We are tied up at buoys on the west side of Southampton Water, which is a major waterway for large ocean vessels. While sitting in the aircraft cockpit early this morning I saw a magnificent sight. The passenger liner SS America sailed by us through a light fog on its way to the English Channel bound for the USA. It is a huge ship, and EA-1 looked like a pitiful little flyspeck on the water in comparison.

I came in off the buoy watch at 1030 this morning. The plane is ready to start the trip home and so are we, but with full gale warnings in Scotland we aren’t going anywhere yet. And so, another day in Calshot. A nice hot shower and a good shave with my electric shaver would have improved my outlook immensely. Alas, there is only a bathtub (with no towels) and a borrowed safety razor because I can’t use my electric shaver on the 240 volt electricity used throughout England.

After lunch I tagged along with Frank Schneider, Jack Clinton, and some VP-661 pilots who were taking a boat to Portsmouth, across Southampton Water from Calshot. Portsmouth is a large British naval base. The main attraction for us was HMS Victory, the restored flagship used by Admiral Lord Nelson in the battle of Trafalgar, where the British fleet defeated a combined French and Spanish fleet in 1805. We took a tour of the ship, and were all struck by the degree to which the navy was tougher life in those days than it is now. Every gun, every piece of machinery was driven by sheer manpower alone. Our trip back was in an RAF Pinnacle motor launch, driving through a 30 knot gale and 3 foot waves off the Isle of Wight. I was impressed by the seaworthiness of this British boat, obviously built with the roughest English Channel weather in mind. One of its features that I found particularly unusual was what I call “rotating portholes” used in lieu of windshield wipers. Each window in the bridge had within it a round piece of glass, like a porthole, supported on a bearing so that it could spin. Attached to it by a belt was an electric motor that made the porthole spin at high speed. When there was rain, or blue water crashing over the bow, any water on the porthole was quickly dispersed by centrifugal force, so that the operators could see clearly where they were going at all times. Ingenious device. I want one on my PBM!

Wes had the buoy watch tonight. I hit the sack in my room at 2100 in preparation for the start of our long trip home tomorrow.

Friday, 26 September 1952

The British Meteorological Service was pessimistic, But USS Currituck said the Edinburgh seadrome was open, so we departed Calshot at 1100 for the 3 hour flight north. The seadrome is located right off the Edinburgh waterfront and has little shelter from the northeast seas pounding in from the mouth of Firth of the Forth. It was manageable for our PBMs, but rough. After Currituck’s usual delay for boat trouble, we happily went aboard the ship to have an airdale homecoming again. Showers! Shaves! Mail! I had 2 postcards and 6 letters.

We learned that EA-2 (Paul Parks) and EA-3 (Jess Taft) arrived here from Sullom Voe two days ago and sat on the buoy for almost 48 hours. The planes both had full crews on board, and were soon running out of food and water because the seadrome was too rough for Currituck to put over a boat to service them. Finally, Timbalier came in last night and sent supplies out to the planes. This morning the seadrome calmed down enough to evacuate all personnel except for the buoy watch. Currituck had only one of its six personnel boats in commission. The entire operation is in jeopardy for want of boats. Timbalier will soon leave to set up the seadrome in Reykjavik again, so we are stuck with Currituck’s marginal capabilities. Another problem is that the squadron has not been paid since leaving Bermuda. Our pay records, supposedly mailed to the ship, haven’t arrived yet. This obviously is not good for morale.

I took the buoy watch tonight in order to bring EA-1 aboard the ship for a 120-hour check in the morning.

Saturday, 27 September 1952

“A boat, a boat, my kingdom for a boat!” (With apologies to William Shakespeare). On the buoy we aroused ourselves at 0500 for the scheduled 0600 hoisting aboard. For want of boats we didn’t get started until about 0800. At 0830, with EA-1 six feet off the water and going up, the crane broke down. We were put back in the water to wait. Finally got aboard at 1030. Cold, rainy day. With our airplane in check I could have gone ashore, but decided to wait for a better day.

Sunday, 28 September 1952

Sunday, 28 September 1952

EA-1 was put back in the water at 0830. I turned her up to check the engines, they are ok, and now we are ready to go home!

Got dressed up in blues after lunch and took the 1230 liberty boat to town with Jess Taft. Sunday is not a good day to visit Edinburgh because the shops are mostly all closed. We did get a look at the town and walked up to Edinburgh Castle, the principal tourist attraction. The town consists of very old buildings, all black with age and soot. No skyscrapers. The houses burn very smoky fuel for heat, and as a result the town has a perpetual overcast of haze and smoke. Very unfavorable for taking kodachrome pictures. Edinburgh is not a place I’d care to stay in very long. I returned to the ship in time for the evening meal, then settled down to write letters and study my correspondence course.

Monday, 29 September 1952

Up at 0630 for breakfast. Took the 0915 boat to town with Jess Taft to mail letters, check out the shops, and price woolen goods. Discovered the prices on Tartan plaids are higher here than on Bermuda. Tagged along with Jess while he made the rounds of secondhand silver shops. The story is that many old families have sold their silver services to raise cash in Britain’s weak postwar economy, and that the used silver is on sale at bargain prices. Not interesting to me. We returned to the ship after eating lunch ashore.

A brisk northeast wind blowing since last night brought 4 foot swells and a rough sea into the seadrome area. It threatens to halt the boats again. Mail arrived, and included the VP-49 pay records (at last). Special payday was held after supper and the hardier souls went to town on liberty with their full wallets The town depresses me, and for sure I don’t want to spend the night there if the boats stop running again, so I decided to remain aboard ship.

Tuesday, 30 September 1952

The water was too rough to relieve last night’s buoy watch this morning. I visited the ship’s aerology office and learned that the easterly wind is expected to continue through tomorrow at least. This bodes ill for our scheduled Thursday departure.

Frank Schneider purchased a Shetland pony for his children while he was in Sullom Voe. It has been living in the afterstation of EA-9 for almost 3 weeks. The crew wasn’t very happy about it at first, but now they seem to have adjusted, and proudly fly a “pony flag” from their aircraft while it is tied up to the buoy. One of the Edinburgh newspapers got wind of this (they may have smelled it) and managed to take a boat out to the plane to interview the crew and the pony. The interview, complete with a photo, made the front page of the Edinburgh newspaper today. The pony had no comment. Earlier the pony, along with Frank Coleman and the rest of the Edinburgh buoy watch, had a close call when EA-9 began taking on water in the open afterstation hatches during the rough weather. The crew noticed it before the situation became critical, and successfully pumped it out with the aircraft bilge pump.

The wind blows and blows, and I wonder if we will ever start for home? Most of the ship’s boats have been taken in to the Edinburgh docks because of rough water around the ship. Poor Bill Greenleaf and his buoy crew were on the buoy last night, all day today, and will be there again tonight.

Wednesday, 1 October 1952

The strong northeast wind continues. Once or twice today the sea was even too rough for the liberty launch, the ship’s most seaworthy boat, and people stranded ashore couldn’t get back to the ship. This evening the Air Department took a drastic step. It loaded the relief buoy crews in the liberty launch, along with food and water, and sent it to the aircraft anchorage with an empty rearming boat following. Once they were in the vicinity of a plane, the relief crew was transferred to the rearming boat one at a time, and then from the rearming boat to the plane. (The liberty launch is too large to come alongside an airplane.) This process took a couple of hours, but was certainly better than nothing for the buoy crews who had been in the plane without respite for 48 hours.

I was glad to get off that madhouse of a ship and back to the nice quiet airplane. We are scheduled to leave for Iceland tomorrow morning, but the seadrome remains very rough.

Thursday, 2 October 1952

EA-1 was the first aircraft off for Iceland, airborne about 0900. The swells were very large, and we made it into the air only on our second try, a hairy crosswind, cross-swell takeoff run. The seadrome was much too rough for a heavy loaded takeoff, but in our anxiousness to be gone from this place we wouldn’t admit that. Half way to Reykjavik, about 2 ½ hours out, we got a Reykjavik weather forecast predicting 500 foot ceiling, 2 ½ mile visibility, showers, and surface winds 40-50 knots. Along with this came a message from USS Currituck directing everyone to return to Edinburgh, so we executed a 180 degree turn and retraced our path. By this time, because of the rough seadrome, the returning planes were landing in a sheltered area by the Forth Bridge, about 6 miles from the ship. After we landed at 1500 it took us 30 minutes to taxi back to the seaplane anchorage. Lack of boats was a problem, as usual. It was 1900 before a boat finally came to take us back aboard Currituck.

The squadron’s net score for this bad day: EA-6 lost an engine on take-off, and in the resulting hard landing bent a rudder and broke a flap section. EA-4 developed a bad oil leak after her first takeoff. She returned, landed, fixed it, took off again, developed another oil leak, and finally returned again because of the weather. EA-8 lost a prop governor. Everyone lost some temper. My consolation at the end of the day: There was mail waiting for me at the ship.

Friday, 3 October 1952

Friday, 3 October 1952

It was another struggle, but we finally got EA-1 off the waters of Firth of the Forth at 1030, and landed in Reykjavik harbor about 6 hours later. The weather enroute was beautiful except for one small front in which we picked up a bit of ice. This is not a desirable time of year in Reykjavik, though. Surface air temperature was just +3 degrees C, which is simply too cold for comfort in seaplanes. Nine planes were sent to Reykjavik in an effort to make up for the lost day yesterday by departing this evening for Argentia. However, the Argentia weather was too clobbered to permit an early evening takeoff, so we refueled, made a buoy, and sat there. I had the buoy watch, and the bow heater was out again. Brrrr! But, at least it is a pleasure to get away from the miserable Currituck and be with a tender that operates efficiently, USS Timbalier.

I got a boat to the ship at 0800, in time for breakfast in the wardroom. With 9 planes and full crews here, Timbalier is crowded like a sardine can, but nevertheless we all prefer it to Currituck! We hoped to depart Iceland tonight, but Aerology predicts 50 knot headwinds enroute and fog in Argentia, so we must wait another day at least.

Sunday, 5 October 1952

A fierce storm hit Reykjavik at 0630 this morning. The wind increased to 50 knots, with gusts to 60. The planes could avoid dragging their buoys only by turning up their engines. EA-3 was almost lost on the rocks because her APU quit. It would not restart, and she couldn’t start her main engines on batteries alone. At the last minute, with the rocks threateningly close and EA-8 getting into position to attempt to give her a line for towing, Crew 3 managed to get the APU running again, start the engines, and move out of harm’s way. After 7 hours of this, the wind finally died down to just 10 knots, and Timbalier put over a rearming boat to send out food and relief crews to the aircraft. On the boat’s 3rd trip, with Frank McCoy, Casey Campbell and me and our crews aboard, the wind whipped up to 50 knots again. We were caught moving downwind from the ship to the planes, and discovered the boat didn’t have enough power to safely come around into the teeth of the gale. The coxswain continued to maneuver the boat downwind while we and our personal luggage got soaked by the icy salt water blowing over us. It was a dangerous situation. Finally, the coxswain found a small outcropping of land and skillfully moved behind it to give us some shelter from the wind. He then carefully ran the boat aground on a rocky beach. We got out, built a fire with some driftwood, and waited for the storm to subside. We were out of sight of the ship, so we dispatched one officer to walk to a nearby building to attempt to contact the ship by telephone and advise her of our situation. After a while the wind abated, we refloated the boat on the flood tide, and carried on with the aircraft crew exchange.

me and our crews aboard, the wind whipped up to 50 knots again. We were caught moving downwind from the ship to the planes, and discovered the boat didn’t have enough power to safely come around into the teeth of the gale. The coxswain continued to maneuver the boat downwind while we and our personal luggage got soaked by the icy salt water blowing over us. It was a dangerous situation. Finally, the coxswain found a small outcropping of land and skillfully moved behind it to give us some shelter from the wind. He then carefully ran the boat aground on a rocky beach. We got out, built a fire with some driftwood, and waited for the storm to subside. We were out of sight of the ship, so we dispatched one officer to walk to a nearby building to attempt to contact the ship by telephone and advise her of our situation. After a while the wind abated, we refloated the boat on the flood tide, and carried on with the aircraft crew exchange.

After operating the engines for so long during the storm, it was then necessary to refuel all the aircraft, since the long flight through headwinds to Argentia would require all the fuel we could carry. I was sitting in the cockpit of EA-1, listening to the VHF radio as EA-8 taxied out to make the refueling buoy astern of the ship.

Suddenly the cry “Emergency!” went out over the radio. In the next few frenzied moments radio conversations indicated that EA-8 was sinking. The trouble arose when the plane, taxiing into position astern of the ship for refueling, had to turn away for another pass at the refueling buoy. A line attached inside the airplane and trailing outside through the tunnel hatch prevented the tunnel hatch from closing. When the pilot applied power on one engine to turn the plane away from the ship, the bow rose and the afterstation lowered in the water causing the open tunnel hatch to become a large hole in the bottom of the aircraft. The crew in the afterstation was unable to close the hatch before large amounts of water entered the aircraft. By the time the unlucky pilot, Frank McCoy, realized what was happening it was too late to prevent the plane from sinking, so he applied power on both engines and taxied the airplane unto a rocky beach to save what he could. EA-8 suffered strike damage, good only for salvage. Fortunately no crew members were hurt.

Suddenly the cry “Emergency!” went out over the radio. In the next few frenzied moments radio conversations indicated that EA-8 was sinking. The trouble arose when the plane, taxiing into position astern of the ship for refueling, had to turn away for another pass at the refueling buoy. A line attached inside the airplane and trailing outside through the tunnel hatch prevented the tunnel hatch from closing. When the pilot applied power on one engine to turn the plane away from the ship, the bow rose and the afterstation lowered in the water causing the open tunnel hatch to become a large hole in the bottom of the aircraft. The crew in the afterstation was unable to close the hatch before large amounts of water entered the aircraft. By the time the unlucky pilot, Frank McCoy, realized what was happening it was too late to prevent the plane from sinking, so he applied power on both engines and taxied the airplane unto a rocky beach to save what he could. EA-8 suffered strike damage, good only for salvage. Fortunately no crew members were hurt.

It was my turn for the EA-1 buoy watch, and I spent my waking hours that evening contemplating how quickly a routine operation can “turn to worms” when a small mistake is made.

Monday, 6 October 1952

At 0630 the EA-1 APU coughed and gasped a couple of times and then died completely. We were supposed to refuel this morning, but had to wait most of the day for parts to fix the APU first. Without its power we not only could not start the engines, but also had no heat, not even enough to make a pot of coffee. The buoy watch crew and I had cold Spam sandwiches for breakfast and lunch, and by the time the APU was finally fixed I felt like I would never be warm again. We refueled without incident and were cheered by the good news that we were scheduled to leave Iceland tomorrow morning. I came aboard ship for the evening meal, caught the movie, and then went to bed in preparation for an early departure.

Tuesday, 7 October 1952

We were airborne from Reykjavik harbor at 0310Z this morning, just before sunrise. It was a very heavy-loaded takeoff, but fortunately the seadrome was reasonably smooth and we had no trouble with it. We set our course for NavSta Argentia, Newfoundland, and the next 13½ hours were the most tense ones I have ever spent in a PBM.

The great circle distance from Reykjavik to Argentia is about 1450 miles. Even without the prevailing adverse wind it would be a long flight in a 120-knot airplane, and there was no place to which we could divert if we encountered any trouble. We had little margin for error and it was essential that our navigation be as accurate as possible. After we settled down on course I suggested to the skipper that I take over the navigation duties, and he agreed. Headwinds were forecast, but turned out to be much worse than predicted. From 0530 to 0930 our groundspeed was less than 100 knots. It was even less than 90 knots for one particularly dismal hour, causing us to seriously consider turning back to Iceland. Chief Martin, our flight engineer, moved crew members fore and aft until he achieved the weight distribution that gave us the best airspeed, which was about 125 knots. Our cruising altitude was 2000 feet, but after 3½ hours of low groundspeed I suggested to the skipper that we descend to 500 feet, where the wind might be less strong. We learned in ground school that reciprocating engine aircraft get better miles per gallon at lower altitudes, and at 500 feet we could estimate the wind on the surface more accurately and use our driftmeter to help us stay on course. We estimated the surface wind to be 30 to 40 knots. The seas were rough down there and the ride was bumpy, but our groundspeed improved a little after the altitude change.

HF radio conditions were very poor, and after we were out of VHF range of Iceland we were unable to contact any radio station for hours and hours. Chief Hudson, our radioman, used all of his considerable skills to no avail. We were completely alone out there with nobody to talk to. About 7 hours enroute a new complication arose. One of our propellers began to malfunction. The PBM uses Curtiss electric props, and we discovered that we were unable to control one of them. We learned later that it was a burned out prop motor, which meant we couldn’t adjust prop pitch. This would be bad news if we needed more than just cruise power from that engine. There was nothing we could do about it except worry. We couldn’t fix it in the air, and there was no place to land until we reached Argentia.

Gradually, our condition improved. The winds moderated, the air became less turbulent, Chief Hudson finally established radio contact with Argentia and reported our position, and when we arrived over Newfoundland the sun was shining.

Our happiness at being on the western side of the Atlantic again was tempered when we learned that EA-1 needs a new prop and NavSta Argentia doesn’t have one. The skipper decided that he, Wes Bogle and I would leave the plane and crew behind to replace the propeller, and proceed ahead to Bermuda on other squadron aircraft.

Wednesday, 8 October 1952

It was sad for me to say goodbye to EA-1, Bill Greenleaf, Chief Martin, Chief Hudson and the rest of the crew in Argentia, but I did, and left Newfoundland as a passenger on EA-4 at 0900 this morning. We arrived at NavSta Bermuda 8 hours later.

Two days after that I left NavSta Bermuda for good on a Fasron 795 PBM, enroute home to Althea in Detroit, and then on to our new duty station at NAS Corpus Christi. Within a year I would discover the advantages of flying airplanes that had real wheels, didn’t rely upon boats, and didn’t have to wait for a buoy after landing. My last flight in a PBM was on Pearl Harbor Day, 7 December 1954.

Now, looking back from the perspective of 45 years, I have come to realize that those days as a junior officer in VP-49 were some of the most richly rewarding and satisfying ones of my Navy career. They came before the adult responsibilities of family and the burdens of command dulled the fine edge of youth. Lifetime friendships were made there, and unique experiences were shared that none of us will ever forget.

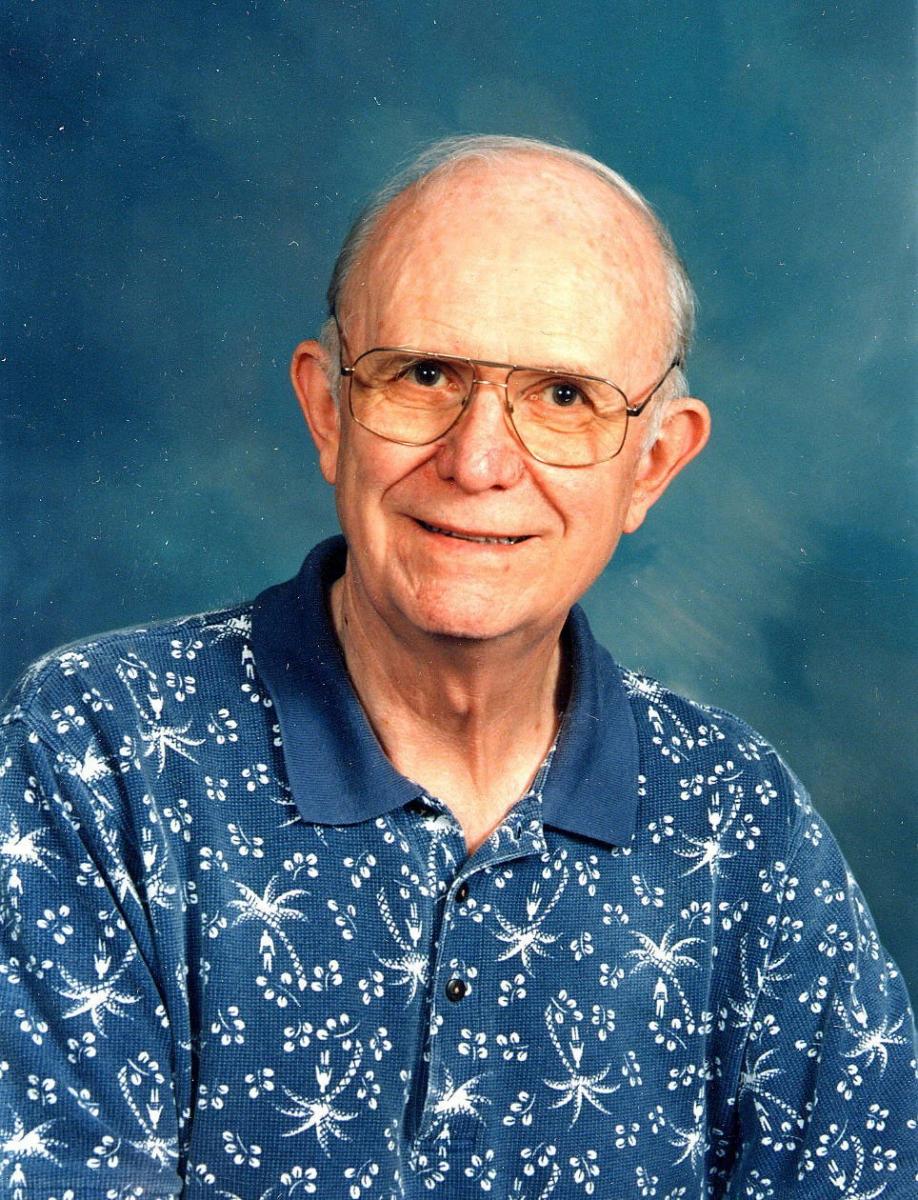

Harley D. Wilbur, Captain USN (Ret)

1 October 1997

Supplementary Material

By Captain Harley D. Wilbur USN (Ret)

9 January 2001

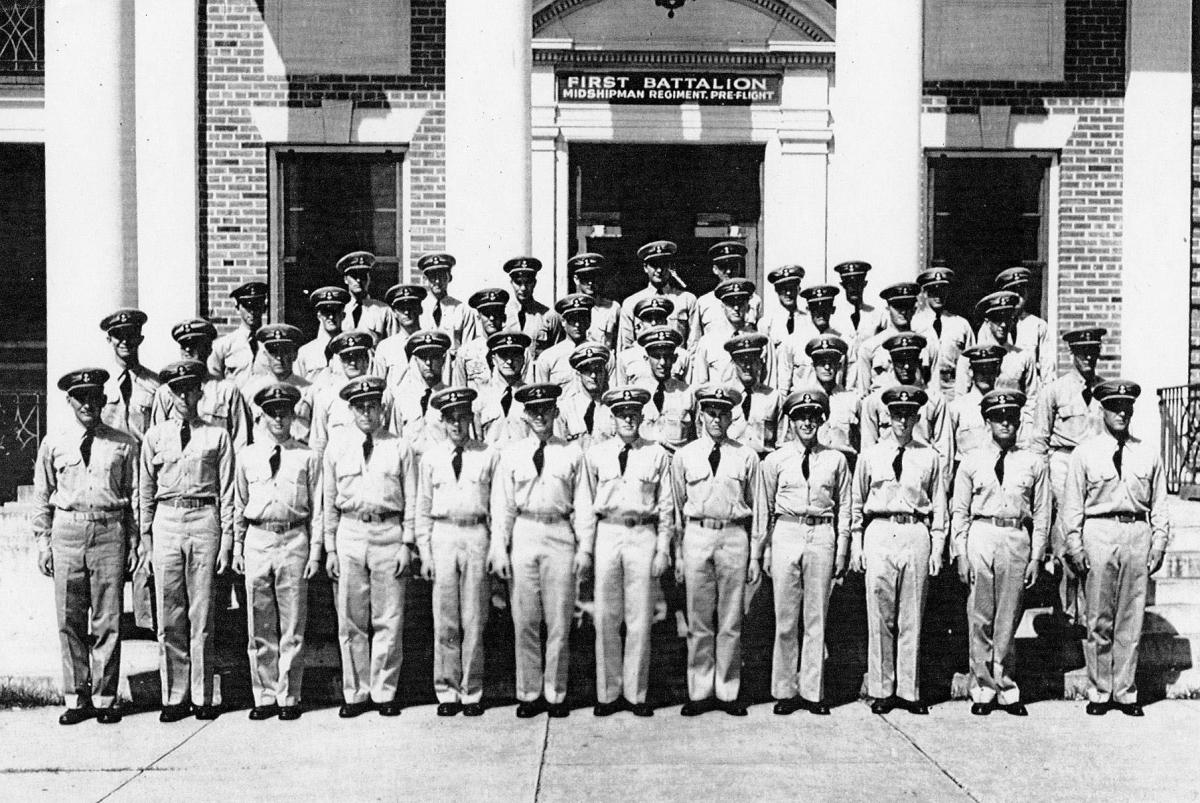

U.S. Naval School, Preflight, Class 11-48

On the occasion of graduation from Preflight School

Flight training started with primary at NAAS Whiting Field. Then came “fun stuff” at NAAS Corry Field, acrobatics, followed by instruments (not fun). Our training airplane was the North American SNJ “Texan”. Here’s the flight line at Corry Field.

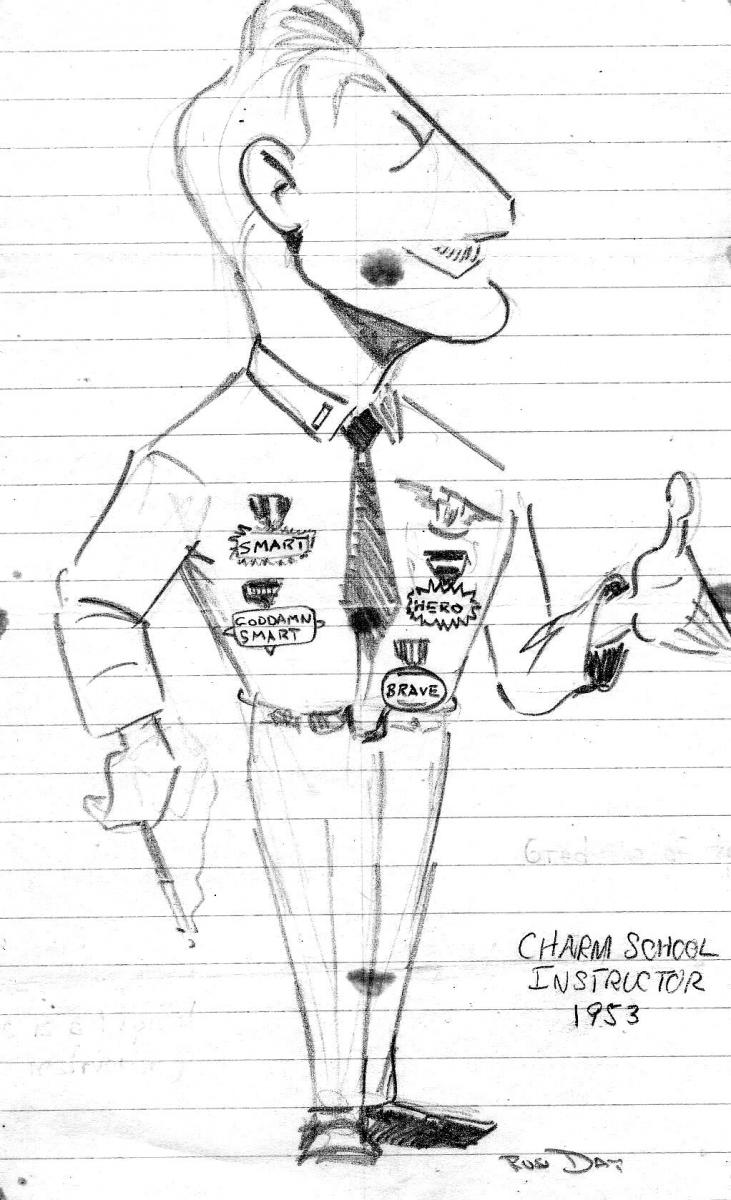

My old friend Russ Day, Preflight Class 7-48, left the active Navy in the 1950s to become a pilot for TWA. He is also an accomplished artist and cartoonist who made it a point over the years to insure that I did not get a swelled head. In 1953 when I was a teacher in the Instructors’ Indoctrination Course, the Naval Air Training Command’s “Charm School” at NAS Corpus Christi, he drew this caricature of LTjg Wilbur in action.

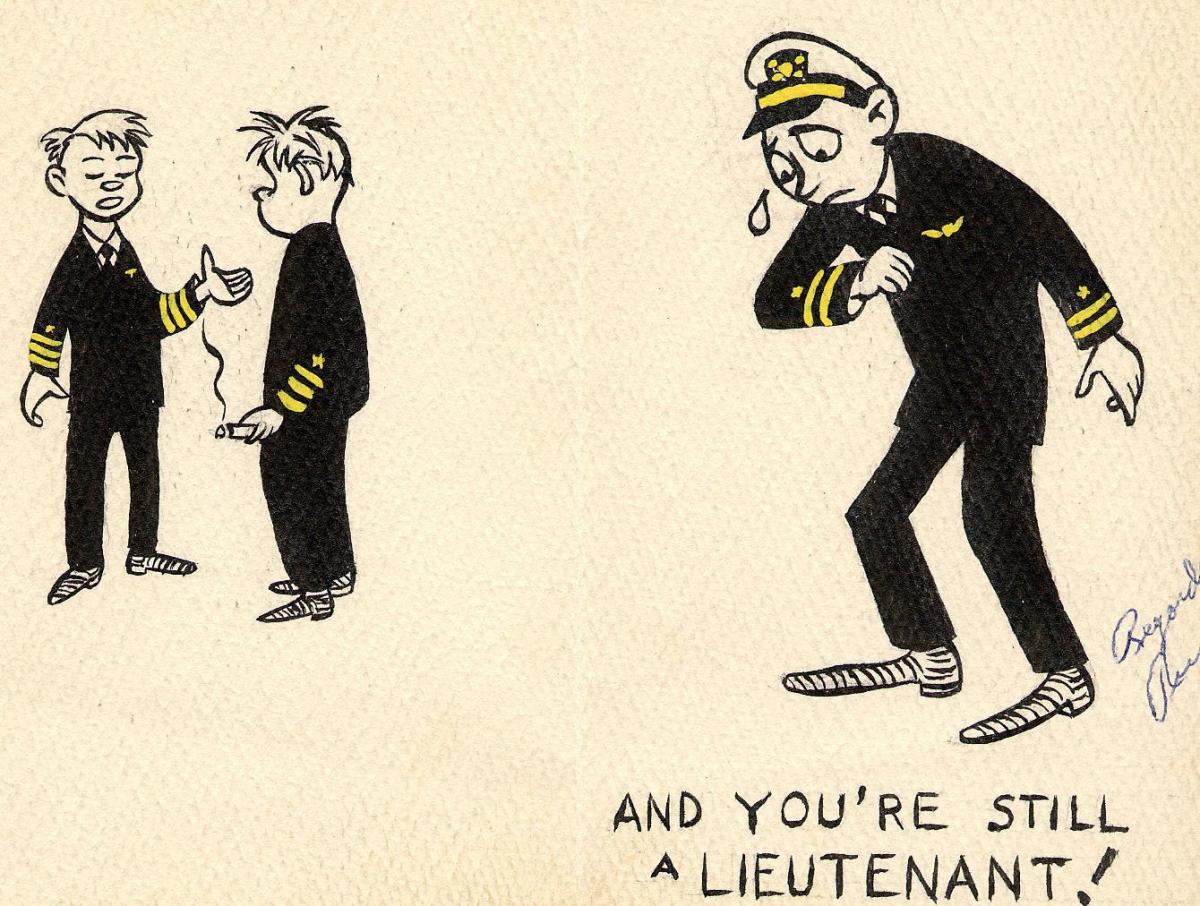

From time to time, Russ Day sent me humorous birthday cards. He had an uncanny way of portraying the truly important aspects of the human condition. This one came in 1956 when I was a line pilot in Air Transport Squadron THREE, a Navy component of the Military Air Transport Service (MATS).

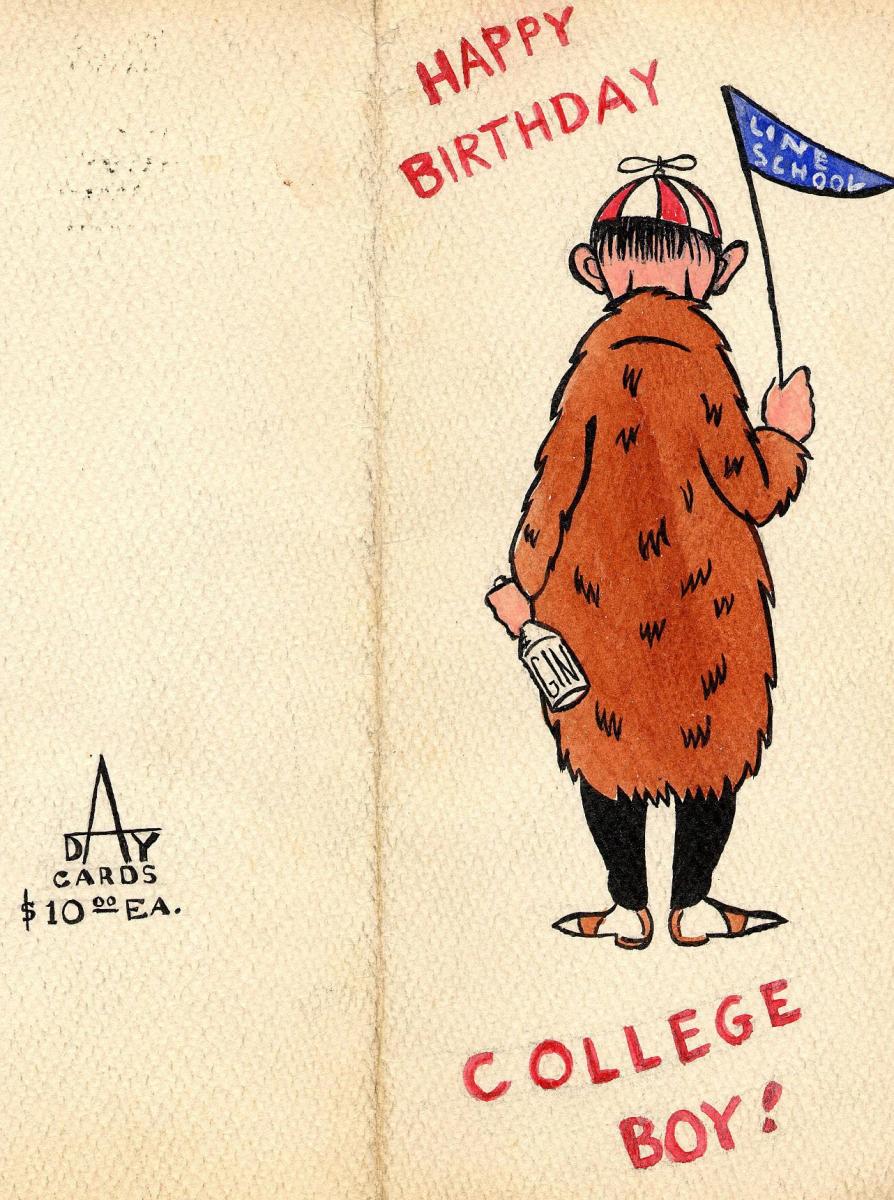

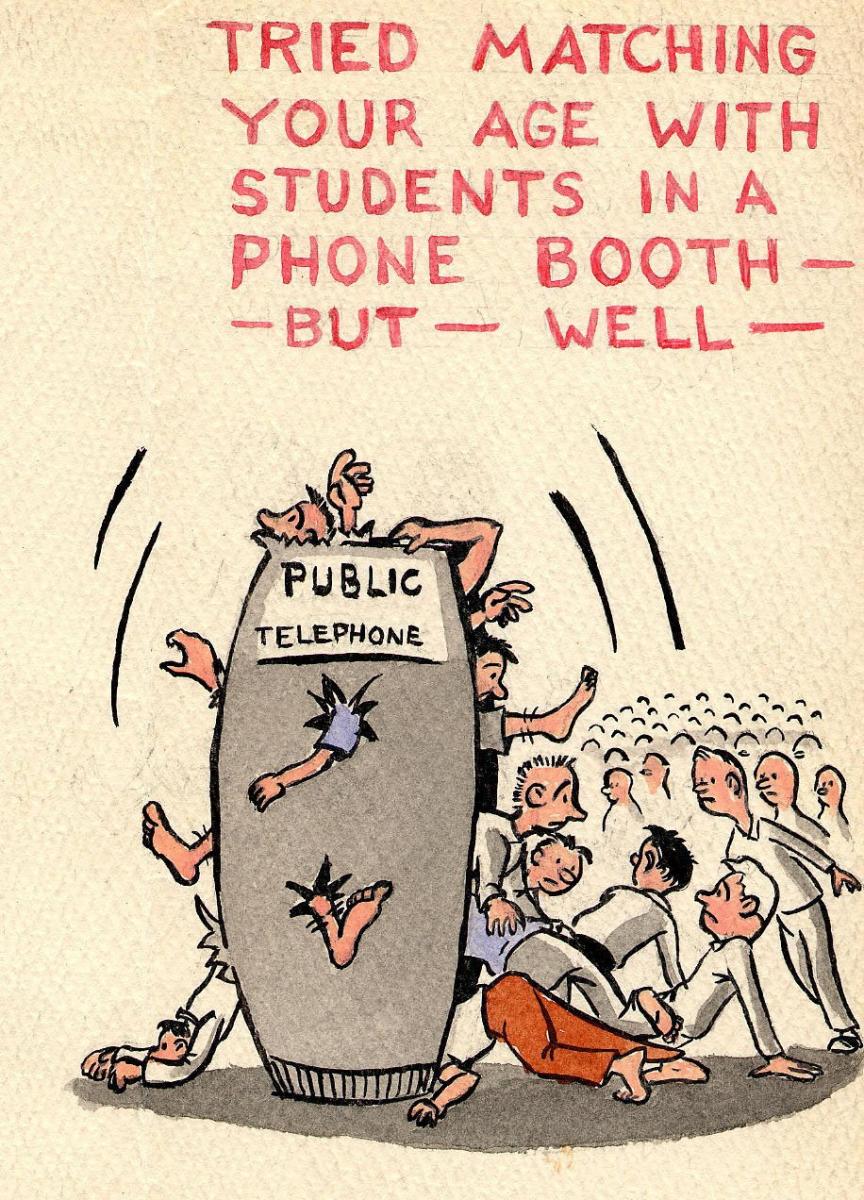

Here’s another of Russ Day’s meaningful birthday cards. This one came in 1959 when I was attending the Navy’s General Line and Naval Science School in Monterey to complete my college degree.

The Red Dart Squadron

Patrol Squadron FORTY-FIVE

1967-1968

The Red Dart Squadron, 1967-1968

Prepared by: CAPT Harley D. Wilbur USN (Ret)

January, 2001

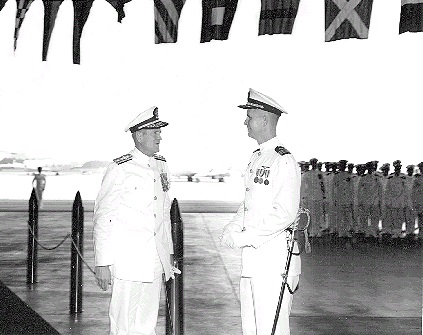

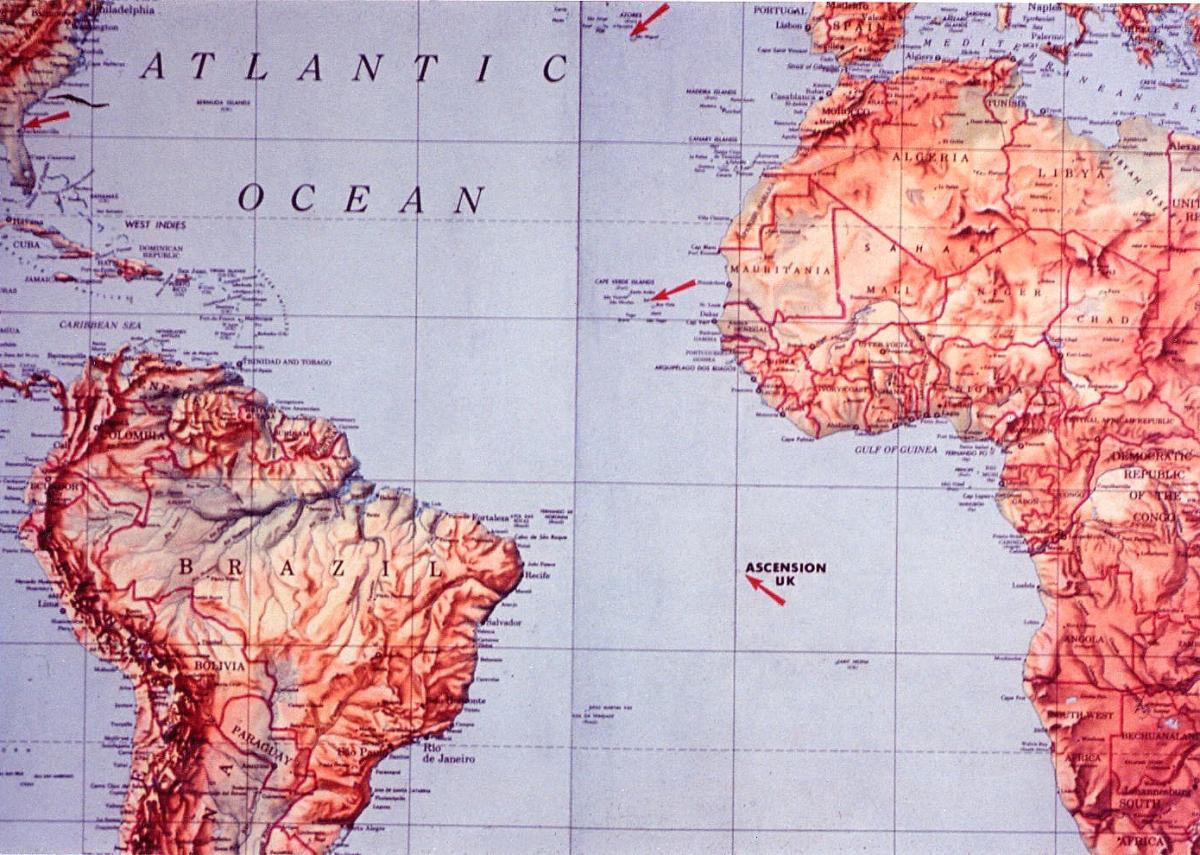

This photo notebook shows some of the activities of the U.S. Navy’s Patrol Squadron FORTY-FIVE during the years 1967 and 1968. From its home port at NAS Jacksonville, Florida, the squadron conducted antisubmarine operations (ASW - The squadron’s primary mission during the Cold War), maritime patrol and surveillance operations, and training missions throughout the Atlantic and Caribbean regions. The squadron’s 1967-68 activities ranged from Thule, Greenland, in the north to Ascension Island in the south, with occasional visits eastward to Bremerhaven, Germany, and Naples, Italy. The squadron was under the command of CDR John W. Townes, who had relieved CDR James H. Chapman in November, 1966. In November 1967, CDR Townes turned over the leadership to CDR Harley D. Wilbur while the squadron was on a Bermuda/Argentia split deployment. The change of command ceremony took place at Kindley AFB, Bermuda, and the squadron was honored to have ADM Ephraim P. Holmes, CINCLANTFLT, as the principal speaker. Leadership changed again in October 1968, when CDR Wilbur was relieved by CDR William H. Saunders III at NAS Jacksonville.

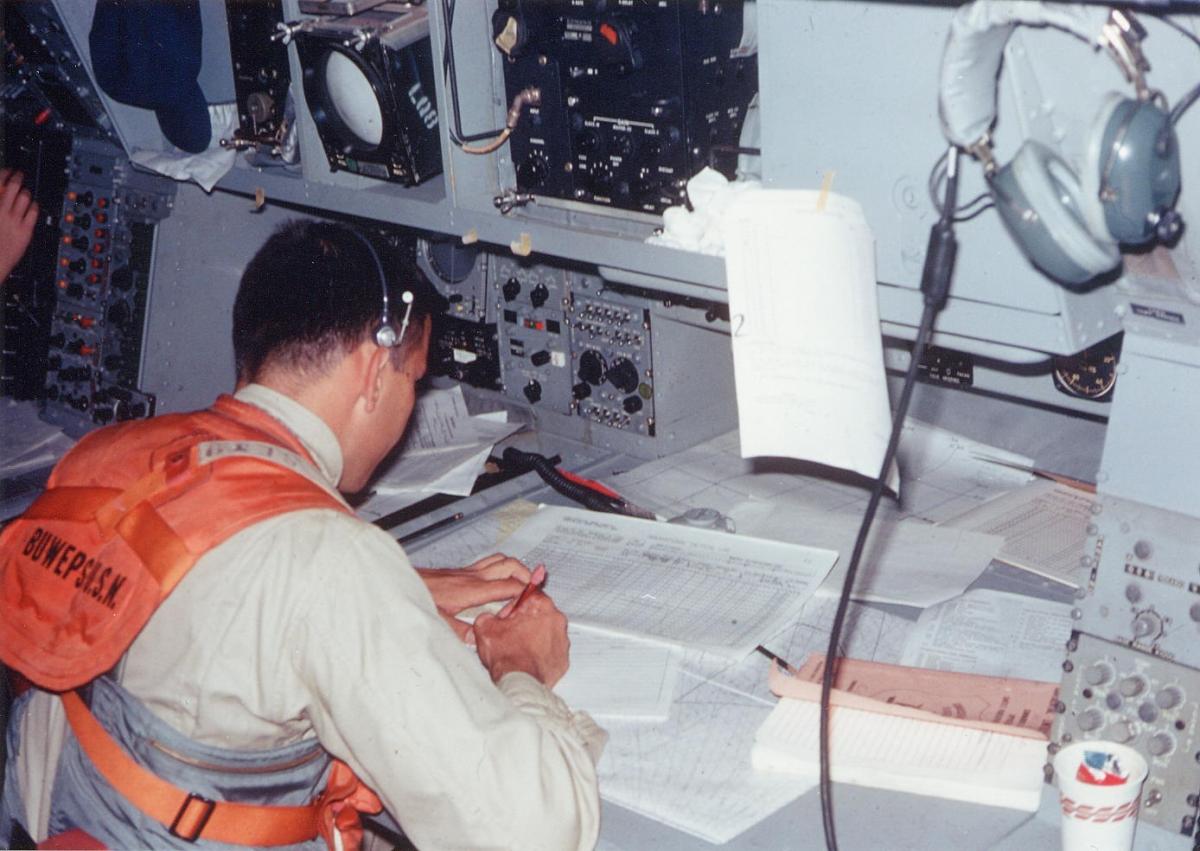

You are invited to come aboard the Exec’s airplane to see what the interior of a Lockheed P3A Orion looked like in the 1960s.

Just climb up this ladder!

This is the main cabin where the members of the tactical crew do their work. We called it “the tube” for obvious reasons.

The leader of the tactical crew was the Tactical Coordinator, whose station was in the center of the tube. This photo shows LTjg Bill Dailey, who flew with me as Tacco during replacement crew training in VP-30 and for my entire two years in the squadron.

The navigator’s table was immediately forward of the Tacco’s station, to enable these two officers to share information and work together during tactical evolutions. The P3A had a rudimentary inertial navigation system, but it wasn’t very reliable. There was no GPS system available then, so the human navigator keeping a hand plot was a key part of the aircraft crew.

The Jezebel operator’s station was also adjacent to the Tacco, to facilitate synergy between these key players in evaluating acoustic data received from sonobuoys during ASW operations.

Two other important sensor stations (not shown) were the Radar operator, who also handled the Magnetic Anomaly Detector (MAD), and the Electronic Countermeasures (ECM) operator. The ECM operator also processed information received from the explosive echo ranging equipment called JULIE.

The “Mark I eyeball” was still an important sensor, and one of the nice things about the P3A was its comfortable seating for visual search. This was especially appreciated by those of us with previous experience in older aircraft like the P2V Neptune and the PBM Mariner flying boat! Shown here is the aft starboard observer’s station in the P3A

The crew ordnanceman handled a variety of search and kill stores under the direction of the Tacco. Sonobuoy racks and launching tubes were readily accessible in the aft part of the cabin. This photo shows the ordnanceman removing a sonobuoy from its storage rack.

The Radio Operator’s station was just aft of the cockpit on the port side. He worked with voice radio, teletype, and as a last measure a CW key for sending Morse code. He also served as a visual observer during tactical operations.

This is the P3A cockpit. The green pilot’s plotter in the center instrument panel enabled the pilot to compare the real world (as seen by him) with the Tacco’s electronic plot of the tactical situation. Plot stabilization (correlation of the electronic plot with the real world) was a continual and serious challenge in the heat of ASW tactical maneuvers. The tight sonobuoy patterns and MAD cloverleaf tracking tactics at 200 feet altitude presented particularly tough problems, which became even tougher during the hours of darkness or in bad weather. Computers and inertial navigation systems were not as reliable as they are today. We did a lot of “visual mark on top” evolutions, and yes, the copilot usually carried a hand plot with grease pencil on his side window for quick reference and backup in case the computers malfunctioned.

At the end of each winter Patrol Squadrons and submarines from Navy bases up and down the Atlantic coast met at Naval Station Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, for Operation Springboard. This was a time for ASW exercises with real submarines, a time to handle live weapons, a time for qualifying aircrews in their required exercises, and a time for general training in operations at a deployment base. This photo shows VP-45 aircraft on the flight line at Roosevelt Roads for Springboard operations in March, 1968.

Here is an ordnance crew loading ASW torpedoes in the bomb bay of the skipper’s airplane, in preparation for a firing exercise. Note the red dart on the side of the aircraft. In those days Navy aircraft squadrons were allowed some creative license in decorating their machines. The red dart was unique to VP-45, and the nickname “Red Dart Squadron” was derived from this insignia.

Although it would seem to be an anachronism in this time of “smart” weapons and nuclear powered submarines, the reliable old MK-54 Depth Bomb, dating from World War II, was still an important weapon in the arsenal of ASW aircraft. Crews practiced depth bomb attacks regularly using small practice depth charges (PDCs). During Operation Springboard they had the opportunity to practice with the real thing. The cart in this photo contains 4 MK-54s, soon to be loaded into the bomb bay of a VP-45 aircraft.

BOMBS AWAY! Here is a string of 4 MK-54 depth bombs straddling a simulated enemy submarine.

This photo shows a U.S. submarine moving at flank speed enroute to her assigned station in preparation for an ASWEX (ASW Exercise) with a VP-45 aircraft during Springboard 1967.

Here is evidence that Springboard strongwasn’t all work and no play. The XO’s crew takes time off for a picnic and some refreshing cold beer. The crew chief was Senior Chief Petty Officer John Bollinger, kneeling on the right, next to the PPC, CDR Wilbur. “Big John” was an experience flight engineer with Eastern Air Lines flying the Lockheed Electra airliner when the Navy began acquiring the P3A (essentially a military version of the Electra). As a member of the Naval Reserve, he applied for active duty in P3s. The Navy was glad to have him back, and he served in VP-45 for many years. It was my good fortune to have him be my flight engineer and crew chief during most of my two years in the Red Dart Squadron. He later became Command Master Chief of VP-49 in 1984, and retired after 47 years (!) of distinguished service in the U.S. Navy in 1988.

VP-45 provided ASW support for the guided missile cruiser USS Columbus and her escort vessels during fleet exercises in early 1967. I later sent this photo to the Executive Officer of Columbus, a personal friend, with the message “Rest easy, Vic. VP-45 is out there guarding you against submarines, with one engine held in reserve in case of contact with the enemy!” (It was standard procedure to shut down one engine to conserve fuel when operating at low altitude.)